Hawk watch season is just around the corner! Every fall, birders gather at ridge tops, sand dunes, and other open spaces to take in the spectacle of hawks flying south, sometimes in huge numbers. In a previous post we gave you a primer on this phenomenon. Here we’ll share a few tips for distinguishing some of the species you may see.

Sharp-shinned Hawk vs Cooper’s Hawk

Both of these hawks belong to a reclusive group called the accipiters. They use their short, rounded wings and long tails to weave through trees while chasing small birds. Watch for them flying in their flap-flap-flap-glide pattern in September and October.

The sharp-shinned hawk (affectionately known as a “sharpie”) and the Cooper’s hawk are fairly similar in color. Adults are slate-gray above and red-brown below, and young are brown above with brown streaks below. A few distinguishing characteristics:

- Size. The sharpie is generally smaller (10”-14”), whereas the Cooper’s is larger (14”-20’). Be careful, though, because females of both species are noticeably larger than males.

- Tail. The sharpie’s tail is square-ended, whereas the Cooper’s is rounded (think C for Cooper’s).

- Habitat. The sharpie prefers to nest in forests, and the Cooper’s will also breed in suburbs.

Broad-winged Hawk vs Red-tailed Hawk

Both birds belong to a group called buteos that have broad wings and fan-shaped tails and often soar high overhead. Some strategies for telling them apart:

- Size. The broad-winged hawk is crow-sized (about 15”), whereas the red-tailed hawk is much larger (18”-26”).

- Tail. The broad-wing has a white band across the tail (not present in young birds), and the red-tail has a reddish tail (brown in juveniles) and a white chest with a dark band.

- Habitat. The broad-wing prefers deep forests. The red-tail will breed in urban areas.

- Time of year. The peak period for the broad-wing migration is approaching: look for huge flocks in mid-September. The red-tail migrates later, with numbers peaking in mid-October to early November, and some birds sticking around all winter.

American Kestrel vs Peregrine Falcon

These are both falcons, with pointy wings and relatively long, slender tails. They both have dark markings on their faces. Sadly, the American kestrel is declining as a breeding species in Massachusetts, and you can help by reporting your kestrel sightings. The peregrine is doing much better: a program to reestablish this species in Massachusetts has been highly successful. Tips for telling them apart:

- Size. The American kestrel is the smallest falcon in North America, at about 7”-8” long, while the peregrine ranges from 13”-23”.

- Color. The kestrel has a rusty tail. Males have blue-gray wings, while the females’ wings are more reddish. The adult peregrine is blue-grey on top, and the juvenile is brown.

- Habitat. Kestrels prefer fields and farmlands. Peregrines nest on cliffs and even on tall buildings in urban areas.

- Time of year. Most American kestrels migrate in September. Peregrines tend to be especially numerous in early October.

Don’t miss this year’s migration: join one of our upcoming hawk watch programs.

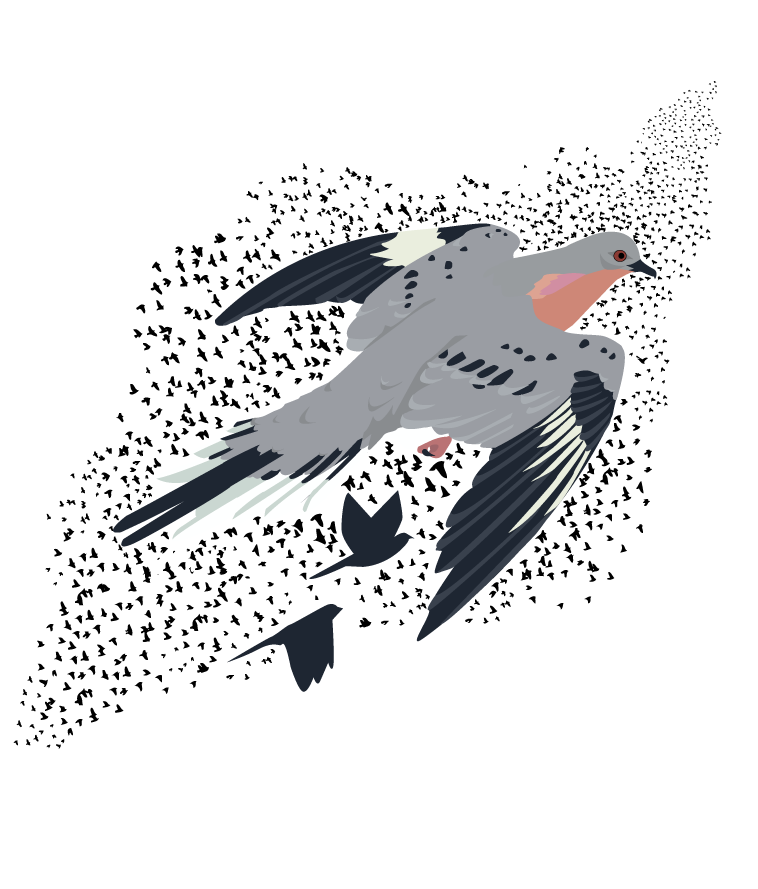

Even with such a dense population, the passenger pigeon fell victim to unrestricted hunting by humans. There are reports of single hunters killing 3 million birds in their careers, reports of one colony having 50,000 birds killed each day for five months.

Even with such a dense population, the passenger pigeon fell victim to unrestricted hunting by humans. There are reports of single hunters killing 3 million birds in their careers, reports of one colony having 50,000 birds killed each day for five months.