“Yaaaaawwwn! What a great nap. Boy, am I hungry…where’d I leave those sunflower seeds?” Sound familiar? Even if long naps don’t give you the munchies, you can probably understand why Black Bears are so hungry when they wake up from their 3–4 month winter hibernation: they lose about 30 percent of their body weight during their seasonal snooze!

When bears enter a den, usually between early November and mid-December, their body temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate drop to conserve energy and help the bear survive the cold, lean winter months. For around 100 days, Black Bears do not eat, drink, urinate, or defecate. Urea, a waste product found in urine, can be fatal in high levels in most animals (including humans), but hibernating bears are able to break down the urea. The resulting nitrogen is used to build protein, which helps bears maintain muscle mass and healthy organ tissue during inactivity. During this time, their stored body fat provides the nutrients and water they need during hibernation, which results in about a 30 percent loss of their body weight.

Bears emerge from the den according to the availability of food, rather than weather conditions, and usually do so in March or April. In communities where black bears have been reported (mostly central and western parts of Massachusetts), it is risky to put up feeders at any time of year: Once a bear has discovered a food source it will revisit that source again and again. If you choose to put up a feeder, you can minimize risk by doing so only from mid-December to the end of February, when bears are denned for the winter. No matter what time of year, though, you should take your feeders down as soon as you hear a report of a bear in the area, for the safety of both the people and the bears.

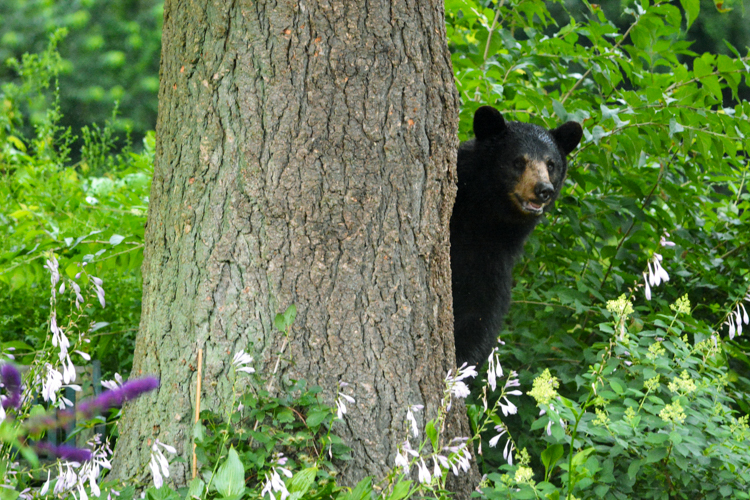

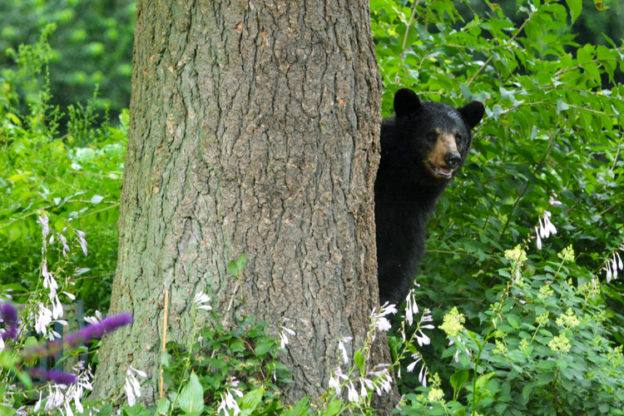

Enjoy these five photos of Black Bears from our annual Picture This: Your Great Outdoors photo contest and, as always, if you see wildlife in your neighborhood, admire them from a safe distance and report any unusual behavior to MassWildlife.