Every November, most migratory birds of the American West are on their way south, but a handful always end up in New England. While it might seem surprising to find a Western Kingbird along the chilly Massachusetts coastline, it can be fairly easy to predict which weather conditions will bring a small wave of western vagrants into the Northeast.

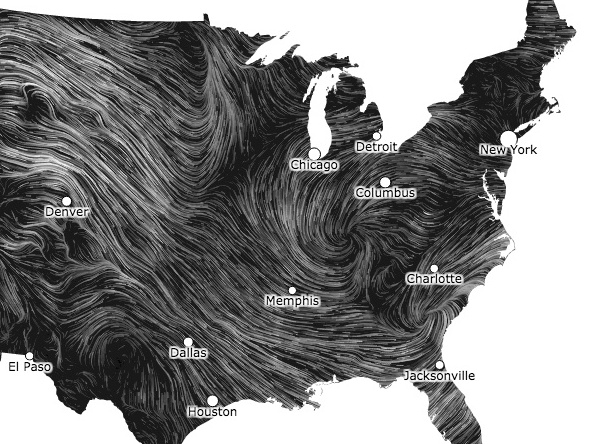

Fronts and storms are key, especially those bringing winds from the southwest. After the breeding season, some migratory species disperse in seemingly random, weather-dependent ways before continuing to the tropics. Additionally, most populations of migratory birds include a few individuals born without their cohort’s navigational abilities. These birds with “reversed compasses” often migrate irregularly during their first year of life.

These vagrants can show up anywhere, but there are a few tricks to looking for them. Watch the weather, and go birding a few days to a week after strong southwesterly winds. Seek out edge habitats, bodies of water, and potential sources of food— like thickets of late-season berries, or low and sheltered areas near coastlines where flying insects persist later into the fall.

The past few weeks have been a promising lead-up to western rarity season, with Cave Swallows already appearing on the South Shore, and a Say’s Phoebe seen in Barre in mid-October.

Right now, conditions look fairly promising—winds over the dry interior of the US are blowing strongly from the northwest, but they connect with two large cyclonic storms moving northeast. Following that, forecasters call for strong southwest winds. It will be interesting to see whether or not the upcoming storm system leaves any vagrants in its wake, and in all likelihood, it will.

Here are some species to stay on the lookout for:

- Cave Swallow: These small birds of the south-central US and Caribbean have begun to show up like clockwork. They arrive almost exclusively at coastal sites after strong pulses of southwest winds, and in recent years, there have been numerous annual sightings several birds at once. The phenomenon of Cave Swallows showing up in the Northeast is fairly new. Cave Swallows were extremely rare in Massachusetts before the last decade or so.

- Ash-throated Flycatcher: These also used to be much less frequent, but in recent years, have been showing up every 1-2 years at coastal sites. A couple have been seen a few miles inland at open, brushy sites like Drumlin Farm in Lincoln and Danehy Park in Cambridge, but with less regularity.

- Western Tanager: Roughly the same patterns as Ash-throated Flycatcher, but with more inland records.

- MacGillivray’s Warbler: One or several show up about every other year. They are mostly detected in farm fields and suburban thickets . Most sightings are from November, though a few exist from the Cape and South Coast regions in the early fall or late winter.

- Mountain Bluebird. These only show up every 3-5 years, having been most recently seen in MA at Turner’s Falls Airport from November 13-16, 2016.

- Townsend’s Solitaire: Almost annually, some solitaires arrive in November and linger until at least midwinter. In Massachusetts, most records are from Cape Ann and Cape Cod, although there are many inland records from Connecticut, Vermont and New Hampshire.

There are plenty of other species that show up well outside of their range in November, from the annual Western Kingbird to the exceptionally rare Common Ground-Dove. Will you be the next Massachusetts birder to find one?

Subscribe to Distraction Displays for more birding tips, news, and updates on Mass Audubon’s conservation activities.