Budding bird enthusiasts love our summer camps, many of which offer special bird-themed sessions. Check out the following opportunities for kids and teens to learn about birds this summer!

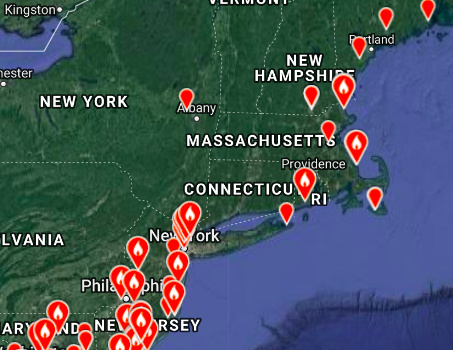

Connecticut River Valley

Raptor Camp (ages 12–16)

June 24–28 Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary, Easthampton & Northampton

Set out to discover birds by foot and canoe at Arcadia and local birding hot spots. See bird banding up close, and learn how to identify birds by sight and sound. An entire day will be devoted to birds of prey.

Greater Boston

Wild about Birds: Curiosity Club (ages 4–5)

Wild about Birds: Naturalists (ages 7–8)

July 22–26 & July 1–3 Broadmoor Wildlife Sanctuary, Natick

Explore what makes a bird a bird, play a game about bird migration, sing in a birdsong choir, and get an up-close look at birds through a telescope. Look inside nest boxes for baby birds and empty nests and meet live birds with an ornithologist.

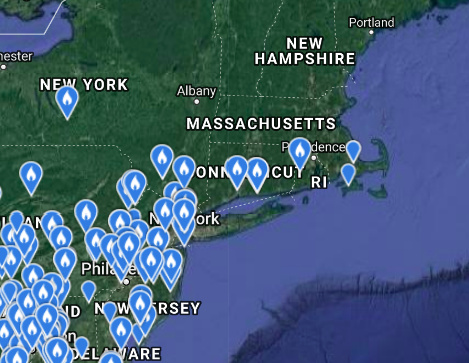

Wild about Birds: Explorers (ages 9–10)

Wild about Birds: Voyagers (ages 11–14)

July 1–3 Broadmoor Wildlife Sanctuary, Natick

Learn when to use binoculars, a birding scope, or your bare eyes to watch for birds. Meet with an ornithologist to learn how scientists study and track birds that migrate. Head off-site to find birds in different habitats, investigate adaptations that allow birds to survive in different environments, and track species and diversity in a bio-blitz.

That’s Wild: Owl Extravaganza (ages 4–6, 7–8)

July 8–12 Museum of American Bird Art, Canton

Back by popular demand: owls soar into camp again this summer! Spend the week on the prowl for owls. See live owls up close, learn about their special adaptations, and create art based on the different owl species found in Massachusetts.

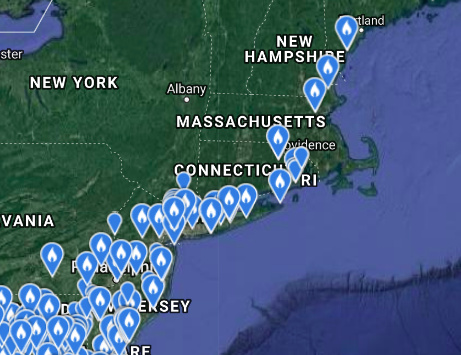

Coastal Birding Adventure (ages 13–17)

August 19–23 Drumlin Farm Wildlife Sanctuary, Lincoln

Travel through the unique coastal ecosystems of Massachusetts, and search for and learn about the unique birds that inhabit them. Spot warblers in Pine Barrens, plovers and sandpipers in the dunes, and terns over the ocean. Check out the latest rare sightings and search for early migrant visitors.

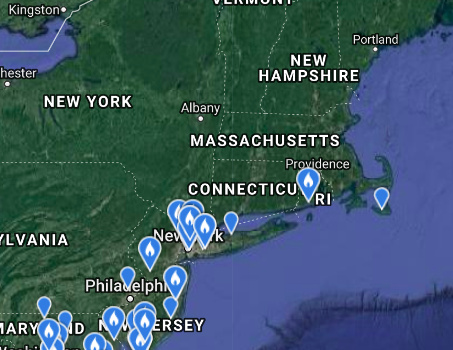

North Shore

Winged Wonders (ages 7–8, 9–11)

July 29–August 2 Joppa Flats Education Center, Newburyport

Using binoculars, scout Parker River National Wildlife Refuge for all kinds of wading marsh birds and soaring birds of prey. In the forest at Ipswich River Wildlife Sanctuary, listen for songbirds on a forest hike, and climb the observation tower and Rockery Grotto. Back at Joppa Flats, get ready for a live wildlife visit from a local raptor rehabilitator, and dissect owl pellets!

Cape & Islands

Fabulous Fliers (ages 7–8)

July 15–19 Felix Neck Wildlife Sanctuary, Edgartown

Why do birds flock together? How do they fly? And why do they sing? Identify and explore adaptations of the many fabulous fliers at Felix Neck, including the osprey, songbirds, and shorebirds.