Before the internet age, informational phone lines were widespread— providing everything from weather forecasts, time of day, or even local rare bird alerts.

Mass Audubon started the original bird hotline in 1954 with some help from a telecom executive, Henry Parker, who happened to be an avid birder.

In fact, the system that Parker developed for the Voice of Audubon came before the widespread use of phone hotlines. The Dictaphone-based system he gave Mass Audubon eventually became the basis for other users to pre-record airline schedules, theater showtimes, and other, more general-interest uses.

The rarities hotline, called “The Voice of Audubon” or VoA, reduced the need for staff to recite sightings to every birder who asked—making it as much a boon for Mass Audubon as for the hundreds of birders calling in each week.

Making the Papers

Shortly after its introduction, the Voice of Audubon was incorporated every week into a bird sightings column in the Boston Globe.

Initially, non-birder Globe interns had to transcribe the bulletin entirely by ear, leading to some amusing misspellings of bird names—such as “wobbling vireos” instead of “Warbling Vireos, “dowagers” instead of dowitchers,” “dick sizzles” instead of “Dickcissels,” and a “pair of green falcons” instead of a “Peregrine Falcon.” Eventually, a written transcript was made available to anyone interested in printing the week’s bird sightings.

Changing Tastes

The Voice of Audubon became a wildly popular model, with similar call-in lines eventually cropping up in most US states. The nationwide rare bird alert even made it in the birding-centric Hollywood movie, The Big Year.

Email changed everything for birding hotlines. With the advent of the listserv, or email message board, call-ins to the Voice of Audubon began to decrease.

Listservs went out of vogue when eBird emerged on the scene, revolutionizing how birders reported their observations. Still, some preferred listservs for the opportunity to discuss sightings in addition to reporting them, for the way listserv conversations build community, and for the ease of reporting a sighting in text rather than via online form. These needs have also come to be addressed by Facebook groups for bird sightings, adding another medium vying for birders’ time and information.

Standing the Test of Time

Through it all, the Voice of Audubon has held firm as a resource for birders, even as it’s call-ins have declined since the heyday of the 1960s and 70s.

Continuing to publish the VoA serves a dual purpose. Firstly, it informs birders who don’t have access to a computer or who prefer the hotline format. Perhaps more importantly, its existence and regular publication in newspapers serves to raise the public profile of birdwatching among the general public.

Do you ever call the Voice of Audubon, read it in the Sunday Globe, or check out the sightings on our website? Let us know in the comments!

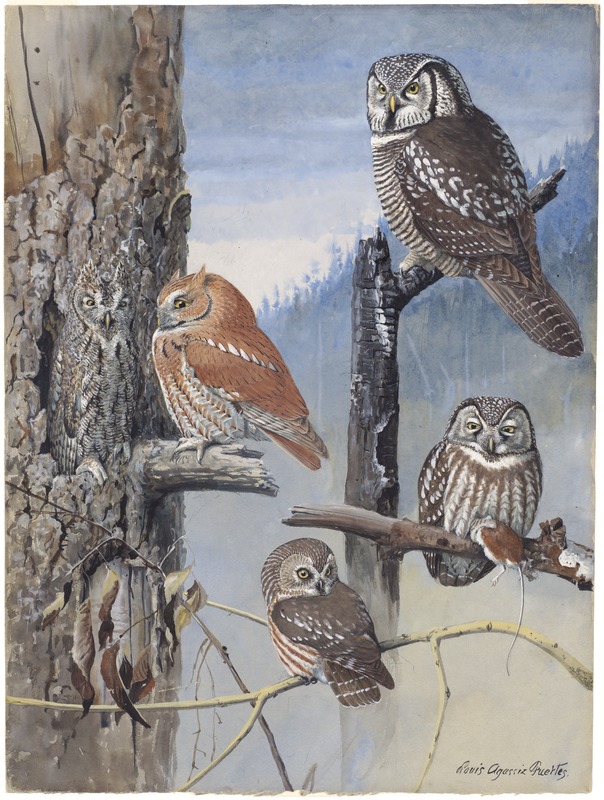

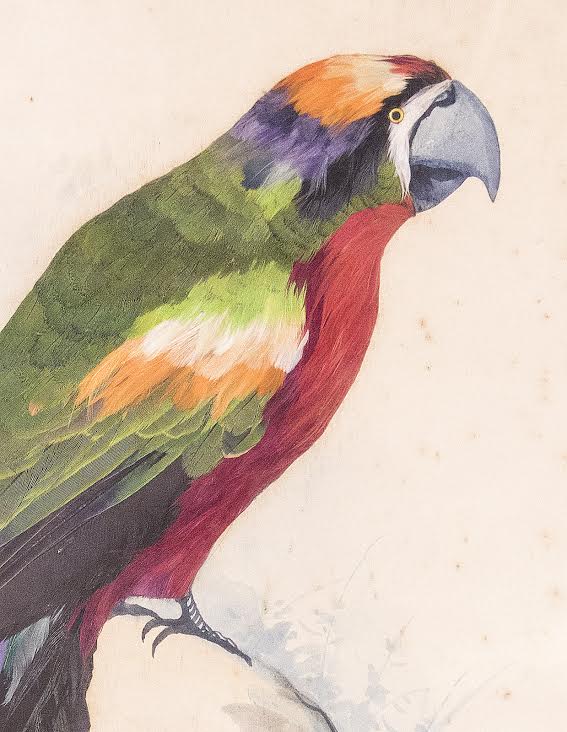

In ornithology, as in most disciplines, there are inevitably “giants” whose profiles stand taller than those of their peers. Such a figure was Edward Howe Forbush, a prominent Massachusetts ornithologist living from 1858–1929.

In ornithology, as in most disciplines, there are inevitably “giants” whose profiles stand taller than those of their peers. Such a figure was Edward Howe Forbush, a prominent Massachusetts ornithologist living from 1858–1929.