Anyone can view a list of radio-tagged migratory birds in transit over Drumlin Farm Wildlife Sanctuary in Lincoln— and follow their next stops in real time.

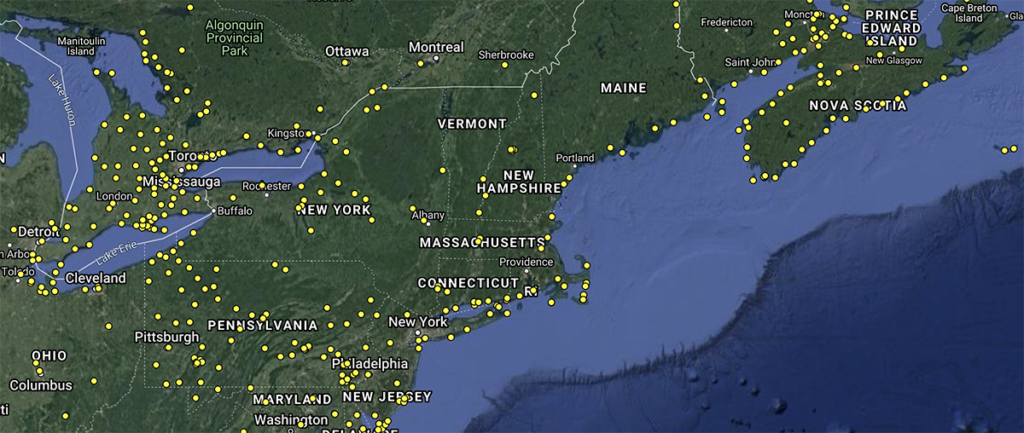

An antenna installed at the sanctuary earlier this summer is part of an international network of receivers (the Motus project) that detect tagged birds as they pass by, helping researchers trace individual migrations across continents.

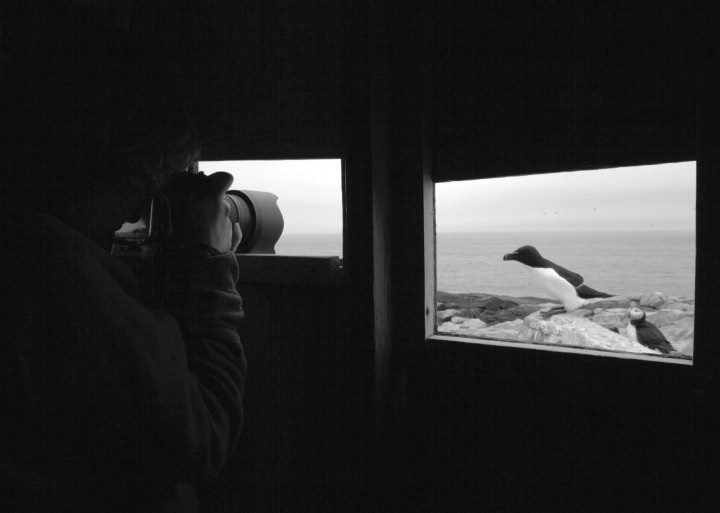

Fly-by-night Visitors

So far this fall, the antenna has picked up some interesting species that began their journeys from as far away as the northern Canadian Maritimes and ended up in Florida and South America.

Most birds that migrate long distances travel at night and feed during the day, making just a handful of stops on thousand-plus mile journeys. As expected, none of the birds stopped near Drumlin, taking just a few minutes in the middle of the night to pass through the area in which the antenna detect birds (about nine miles east-to-west—from the skies over Stow and Sudbury to Watertown and Arlington).

The Cast of Characters

Four Swainson’s Thrushes were among the birds detected, all of which came from a group of 42 tagged in New Brunswick this summer. One bird took a leisurely journey after passing near Drumlin Farm, stopping five days later at a large wildlife refuge between Baltimore and Washington DC, and island-hopping around the coast of South Carolina two weeks afterwards. While Swainson’s Thrushes are a somewhat uncommon sight for birders in the Metro– West area, they’re one of the most abundant species detected by people listening for nocturnal flight calls, suggesting that they pass overhead in larger numbers.

A Bobolink also passed by under cover of night in late September. While Bobolinks breed in the fields at Drumlin (which Mass Audubon manages specifically for them), this individual was from a radio-tagging project based in Maine. It was detected on the DelMarVa peninsula a few days later, but wasn’t picked up by any receivers further south—suggesting it may have made a beeline to South America straight over the west Atlantic, or possibly died.

One Red Knot, a species known for marathon migrations, set the most ambitious pace of any of the detected birds, passing through the Metro –West area before it was detected just two days later by antennae in Tampa and Sanibel, Florida. Tag data from earlier in the year shows this bird spent five days in May of 2021 refueling and moving around the South Carolina coast before rocketing up through Pennsylvania and Toronto over another nonstop two-day journey. Eventually, the signal was lost in central Ontario, with the bird appearing to be on its way to the species’ breeding grounds in Hudson Bay.

Visualizing Migration, Naming Threats

Following pieces of these birds’ routes is more than an interesting and fun window into their world— it provides valuable clues to why some species are declining.

Take Red Knots, for example. Researchers are already using Motus data to show how Red Knots’ reproductive success on their Canadian breeding grounds depends on how much food they can find at stopover sites in the Chesapeake Bay—where their preferred diet, horseshoe crab eggs, is dwindling due to overharvesting.

Other studies have shed light on what stopover sites are most critical for migratory birds, or examine the impact of extreme weather, the overuse of certain pesticides, or other threats.

Meanwhile, Mass Audubon and MassWildlife received a grant together in 2020 to track American Kestrels to their wintering grounds and see if mortality there might be driving their decline (although the pandemic put this work on hold until 2022). We’re also tracking local Barn Swallows— another declining open-country bird— during the summer months, to understand if they forage more successfully over native grassland than farm fields.