Our bird conservation staff spent the past week collecting data at Elm Hill Wildlife Sanctuary, our demonstration site for Foresters for the Birds. Since we’re using this site to show how responsible forest management can enrich bird habitat, we need before-and-after data to compare changes in vegetation and bird diversity.

Birds See Forests For The Trees

The physical structure of a forest directly affects which birds are found there. The amount of vegetation near the forest floor (or “understory”) changes whether or not the forest can host a whole suite species that nest near the ground, like Ovenbirds and Black-throated Blue Warblers. Forests with open midstories (the layer of vegetation between 5–50 feet off the ground) attract flycatching birds like Eastern Wood-Pewees, but dense midstories appeal to Wood Thrushes and Canada Warblers.

The goal of our work at Elm Hill is to demonstrate how every forest species has its own habitat preferences, and how thoughtful land management can create habitat for declining species. Since three quarters of Massachusetts’ forests are in private hands, it’s critical to make these lands as hospitable as possible to wildlife.

Collecting Vegetation Data

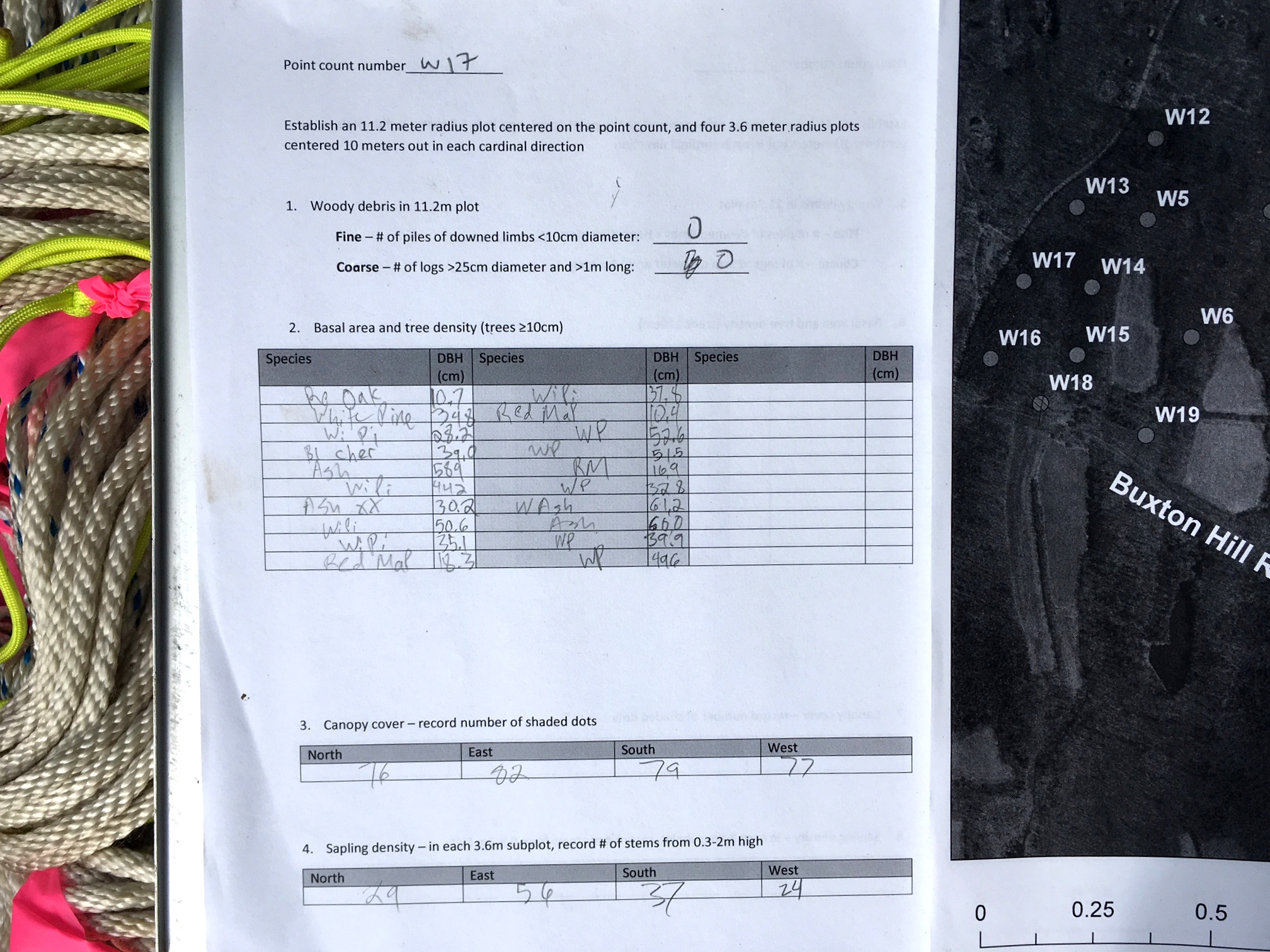

A data sheet we use for recording information about trees and forest structure at Elm Hill.

Before we alter any habitat at Elm Hill, we’re recording these factors at sites where we’ve previously done bird surveys:

- Total woody biomass (i.e., the average size and number of trees in a given area)

- Tree species makeup (i.e., which trees are there, and how many of each)

- Canopy density (i.e., the amount of cover provided by leaves in the treetops)

- Sapling density (i.e., the number of young trees from around 1–6 feet tall)

- Coarse woody debris (i.e., the number of logs and slash piles on the ground)

We outline a 400-square-meter plot with ropes at every site to make sure we collect data from the same area of land each time. This works pretty well until somebody tangles the ropes:

Jeff tangled the ropes. It definitely was not me.

While measuring trees, logs, and saplings is straightforward, you might wonder how researchers measure canopy density— and the instrument for this is quite cool. A spherical densiometer (pictured below) condenses a wide view of the canopy into a small image (much like a fisheye camera lens) with a grid over it. By estimating the percentage of each grid square occupied by leaves or trunks (and adding them up, and taking readings in each cardinal direction), we have a standardized and simple way of measuring canopy density. This also works as a proxy for determining how much light reaches the forest floor.

A spherical densiometer, used for measuring the amount of leaves in the treetops.

Long-term Goals

After foresters have cleared the woods of invasive species and created a variety of spatial habitat types, we’ll be able to show what changes this brings to Elm Hill’s bird species.

Elm Hill contains mostly 70–90-year-old forest, like much of Massachusetts. We’ll manage parts of the sanctuary for birds that prefer young forest, which are in trouble statewide, and in other part’s we’ll try to mimic old-growth forest conditions, which would take over a century to emerge naturally. Hopefully, we can then use this site as a physical example of how foresters and landowners can improve bird habitat on the properties they manage.