Migrating birds are attracted to artificial light at night, and ornithologists are just beginning to understand how that affects their survival.

Recent studies show that the diffuse glow of entire cities can draw migrating birds towards them—and away from more suitable habitat.

There are already hundreds of records of mesmerized birds fluttering around single, isolated sources of bright light— from thousands of migrants trapped in the beams of mile-high searchlights in New York City, to dozens of warblers gathering at the windows of lighthouses.

But until recently, there was limited evidence for how light pollution across an entire region affects where migrants rest and feed.

Radar studies show “clouds” of birds near cities

To test if birds gather disproportionately in brightly-lit cities, migration ecologists looked to doppler radar data. This is the same radar used to create weather forecasts across the country. Doppler radar reveals the density of particles in the air, whether it’s rain, birds, or aircraft, so it’s useful for remotely observing which areas migrating birds are using the most.

Naturalists might expect that migratory birds gravitate towards undeveloped areas, just as most do when they aren’t migrating. But this isn’t necessarily true, according to a team led by scientists from the University of Delaware.

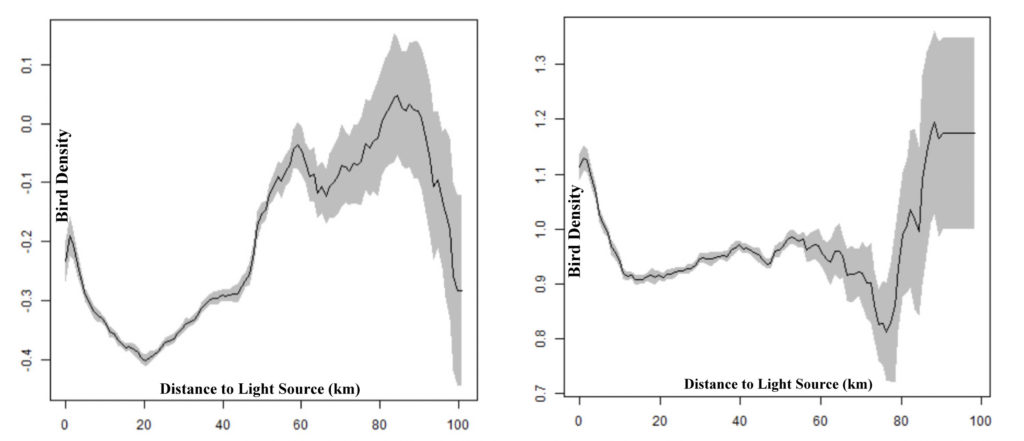

In fact, radar signals consistently show more migrants pausing within a couple of miles of brightly-lit areas than anywhere else within around 30 miles. Migrant density peaks again 50-60 miles away, where the glow of lights on the horizon is dimmer or invisible.

This suggests that artificial light from cities is drawing in birds from greater distances than once believed. The authors of the study write that this pattern risks “impeding [birds’] selection for extensive forest habitat.”

They go on to caution that “high‐quality stopover habitat is critical to successful migration, and hindrances during migration can decrease fitness.”

Prioritizing Urban Greenspaces for Birds

Migratory birds’ attraction to artificial light may be one reason behind the surprisingly excellent birding at greenspaces in cities—something birders have known about for a long time, but struggled to fully explain.

Take Mount Auburn Cemetery, for example: it’s arguably the most famous site in the Northeast to see big numbers of warblers in spring. New York City’s Central Park, too, offers excellent birding that can rival—or outmatch—spring migration in intact forests.

But despite their attraction to the bright glow of cities, birds face increased hazards in urban environments. Most migratory birds feed exclusively on insects, which are harder to come by in cities, and urban ecosystems host more predators per square mile than other habitats.

Modifications as simple as planting native species, reducing insecticides, adding understory and mid-story habitat, or controlling predators could give migrants a much-needed boost at these sites. As long as light pollution continues to be an issue, improving urban habitat and reducing hazards remains important work.