Within buzzing meadows and grasslands, insects of all shapes and sizes are getting to work. These critters may look like they are aimlessly bouncing from flower to flower, but they are fueling themselves up and pollinating in the process. Pollen sticks to the antenna, bodies, and appendages of an insect, which gets transferred to other plants.

To celebrate Pollinator Week, we are highlighting some of our favorite pollination partners.

Red Milkweed Beetle and Milkweed

Monarch butterflies aren’t the only insects that love Milkweed–just look at the Red Milkweed Beetle. They live and feed on Milkweed and in turn, the plant turns the beetle into a bright shade. While these beetles aren’t toxic, their bright color mimics other species that are, keeping would-be predators at bay.

As Red Milkweed Beetles climb to the petal of the flowers to collect nectar, their legs may slip into a pollinia sac. When they take their leg out, pollen clings to them until they go to a new flower, where another sac is waiting for the leg to fall through for pollination. Like the beetle, Carpenter Bees and Painted Lady Butterflies are drawn to the abundant nectar of the Milkweed, making it a common destination for pollinators.

Hummingbirds and Bee Balm

It’s hard to keep up with a hummingbird as it zips around, briefly pausing to hover over the opening of a plant. As the small but mighty bird’s tongue pokes flowers like Bee Balm, it sometimes rattles around the pollen just enough to fertilize the plant. Other times, pollen sticks to the left-over nectar coating a hummingbird’s beak and then gets transferred to another plant that the hummingbird visits .

Bee Balm is particularly a favorite for hummingbirds, especially the minty-scented Scarlet Bee Balm. The tubular red flowers bloom in clumps at the edge of forests and meadows, soaking up the sun in dry soil. Humans enjoy Bee Balm too–it’s perfect to brew as tea!

Hummingbird Clearwing and Viburnum

Hummingbird Clearwings aren’t your average moth–they prefer the heat of the day instead of the cover of darkness. Without keen eyes, you might mistake this moth for an actual hummingbird as it flies to sip up sweet nectar. Their long proboscis coils close to their head as they zoom around and extends when it finds the perfect flower to feed on.

Clearwings frequently visit the shady Viburnum shrub. Viburnums rely on pollinators to transfer pollen to produce berries in the winter and fall. Bonus: Viburnums are a favorite among Tiger Swallowtail butterflies and Sphinx Moths during the summer and the fruit attracts Northern Cardinals and Eastern Bluebirds in the fall and winter.

Baltimore Checkerspot and Turtlehead

Forget chess: the Baltimore Checkerspot is always prepared for a game of checkers with its colorful wings. Don’t get this butterfly mixed up with the Harris’ Checkerspot, which mimics the Baltimore’s pattern but is often slightly smaller and more orange in appearance.

All Checkerspots are meadow species and may be found in both wet and dry meadow communities. Turtleheads, named after their bloom that resembles a turtle, grow in wet areas. Baltimore Checkerspots lay their eggs on the Turtlehead, where the larva will eat and thrive on the plant. Once they turn into butterflies, they come back to return the favor through pollination.

Bumblebees and Tomato Plants

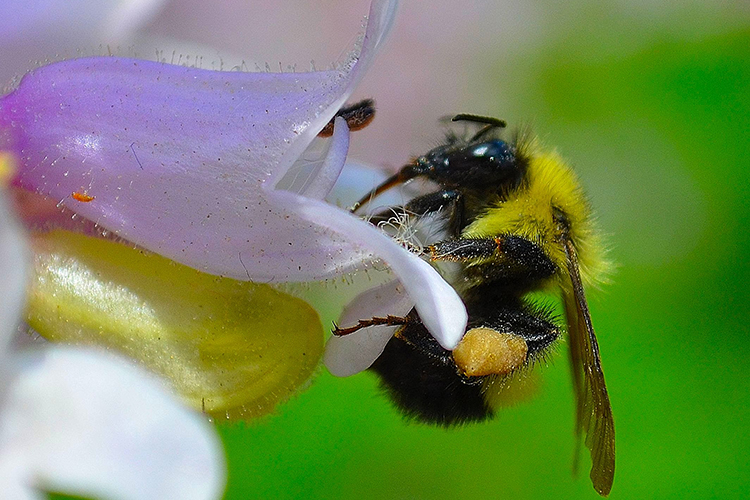

Bumblebees are powerhouses in the pollination arena. In fact, many farms and greenhouses need bumblebees to help fertilize their plants. Worker bees collect nectar and pollen to bring to the Queen and larva for food.

Although tomato plants aren’t a native species, bumblebees specialize in them. They are known as buzz pollinators, because they attach themselves to flowers that have a tight center, like tomato plants, and use their vibrations to open them up. As the flower loosens, pollen can fall out and land in other flowers or onto the fuzz of the bumblebee. As the bees move across the tomato plant, the pollen drops from their hair to pollinate other flowers.

Plant A Pollinator Garden

Bring pollinators to your neck of the woods by planting a colorful range of flowers that looks great and helps your local wildlife. Find out how >