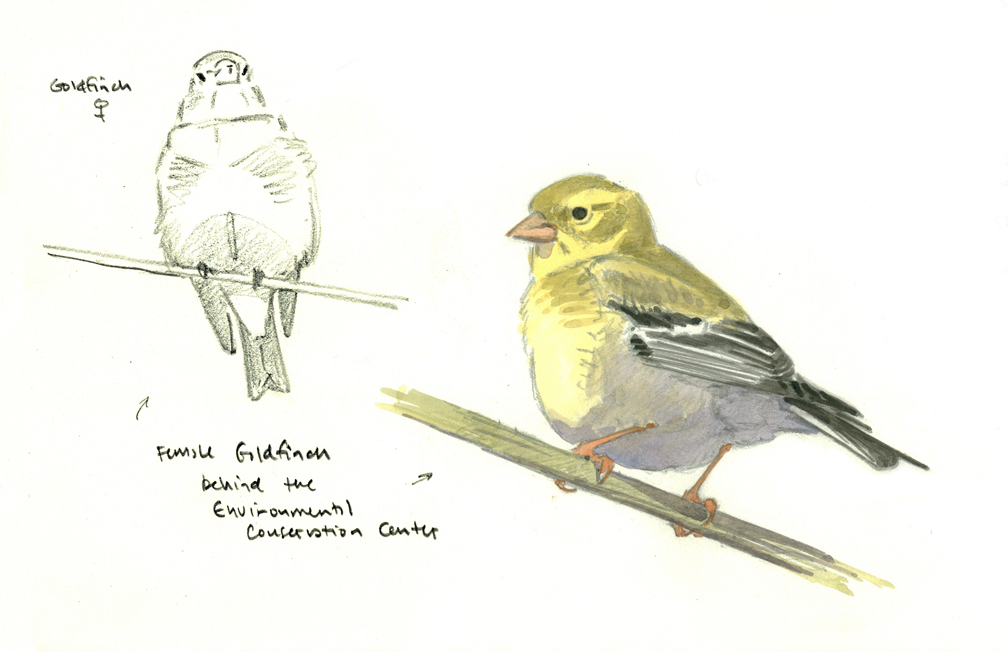

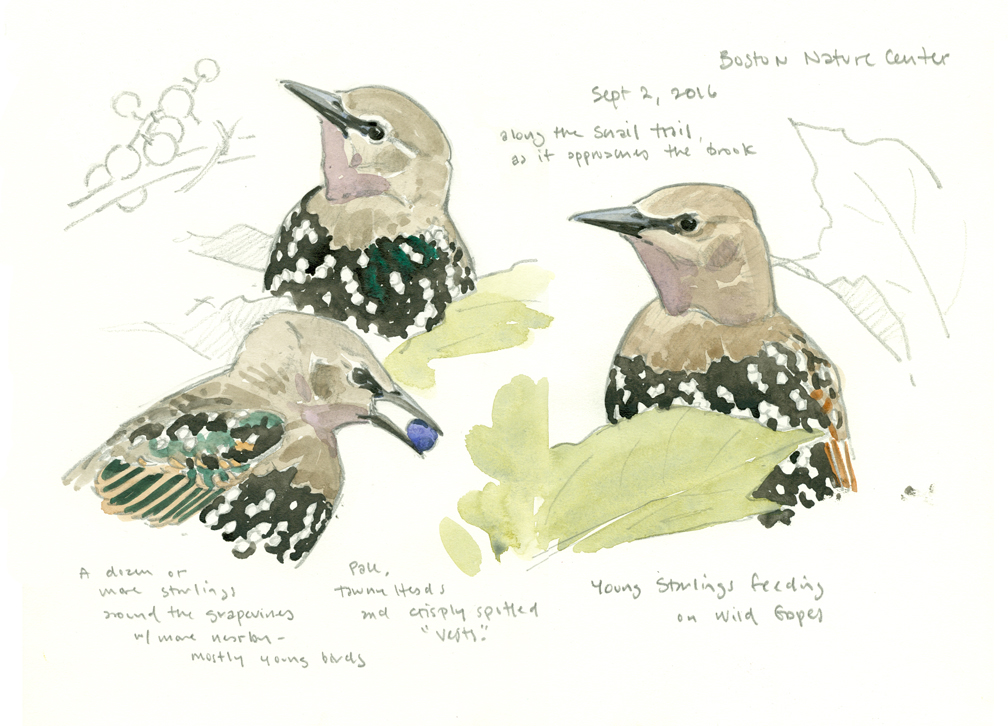

January 29, 2017

Endicott Wildlife Sanctuary, Wenham

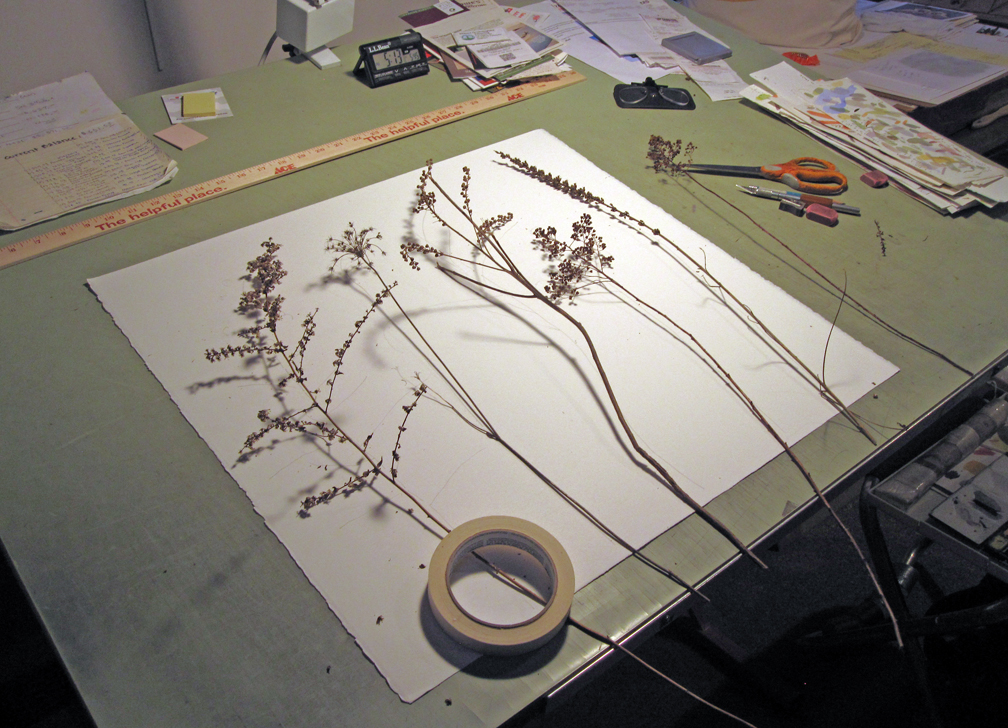

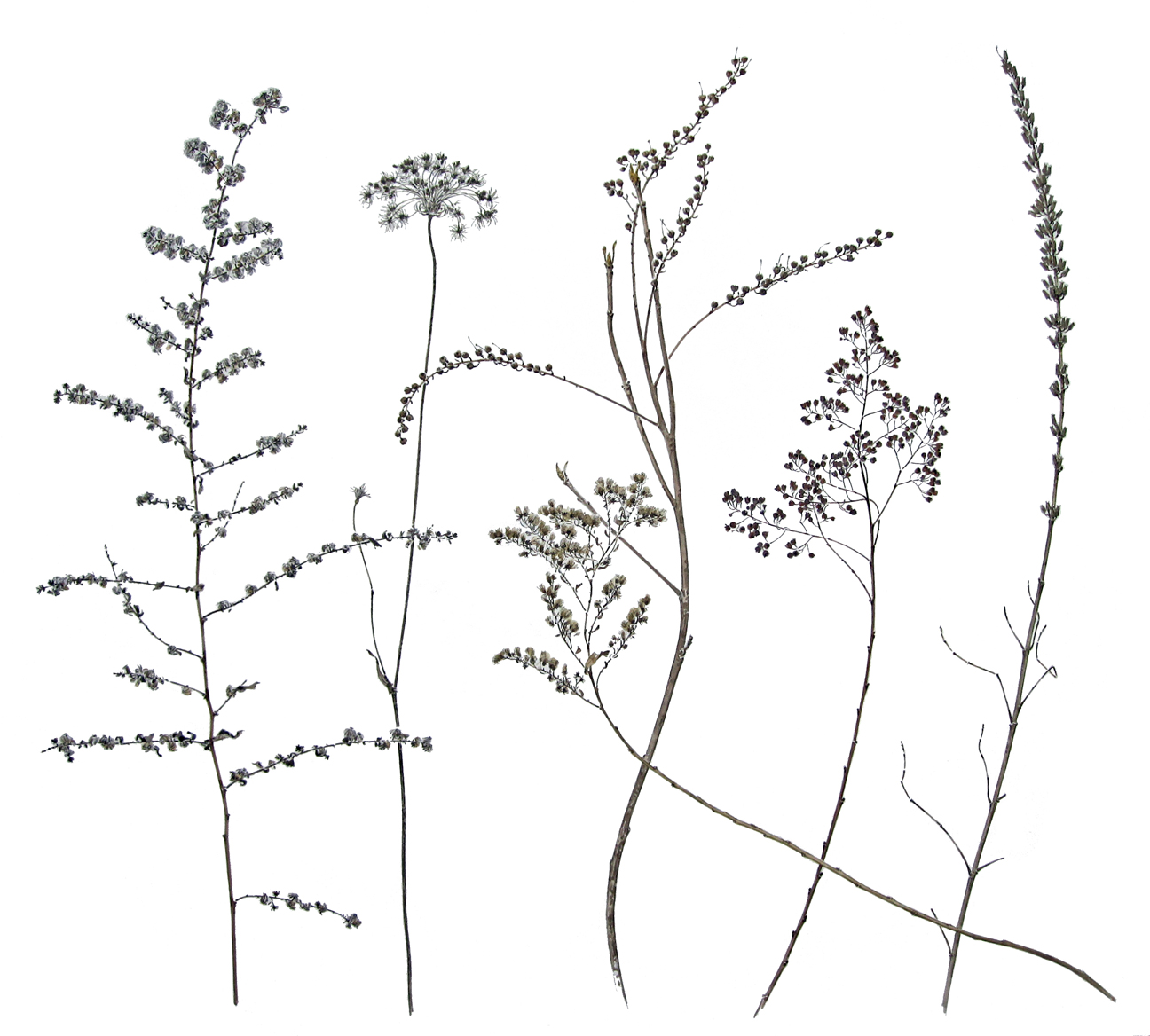

Back in the studio, I spread out the winter stems I collected along the entrance drive at Endicott Wildlife Sanctuary. I arrange the stems on a big sheet of Arches hot-pressed watercolor paper, moving them around and trying out various arrangements until I have a nicely balanced composition. You might notice that the pepperbush in the center arches outward to the left and right, while the two outermost stems curve gently inward, bracketing and containing the stems in the center.

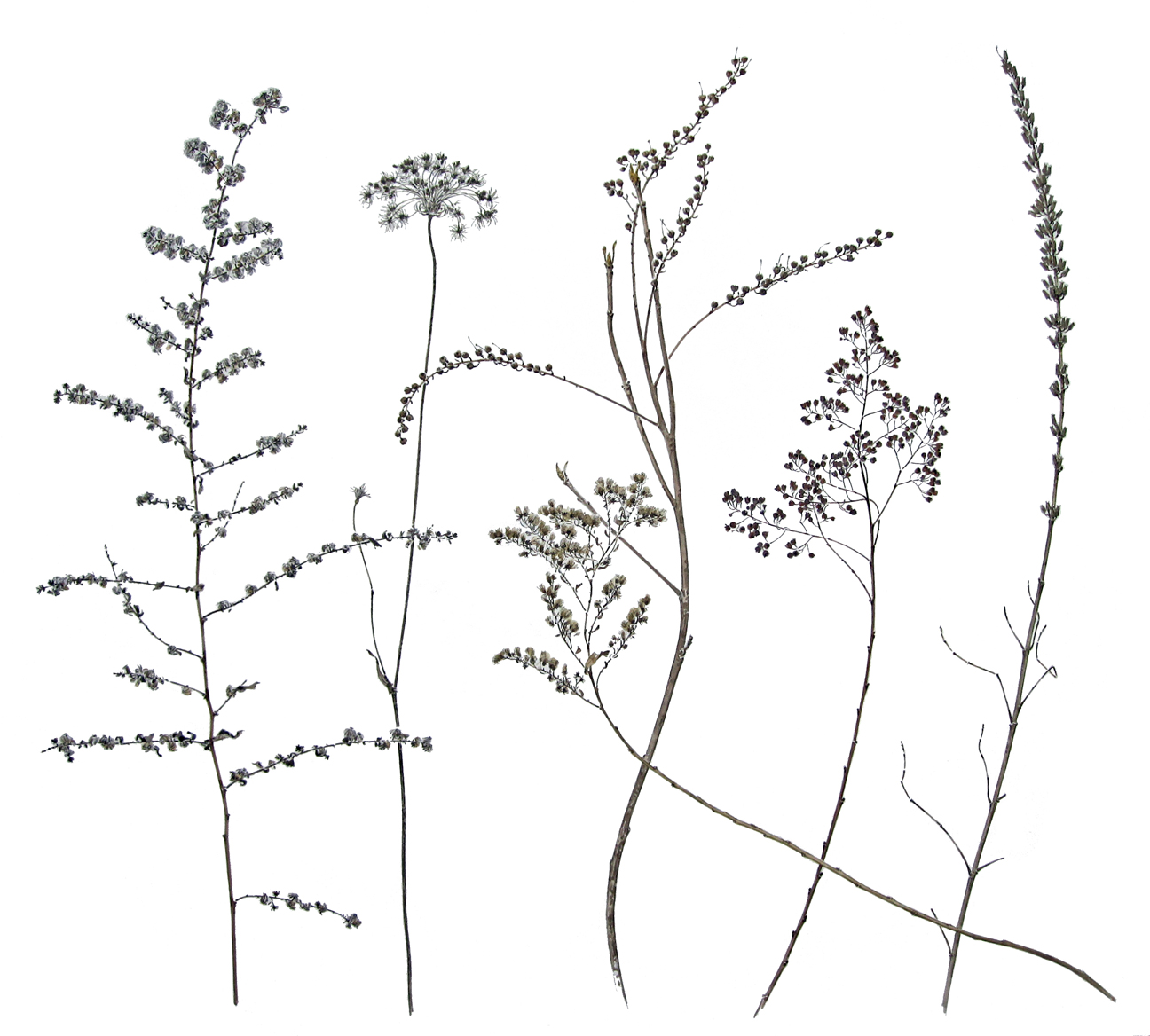

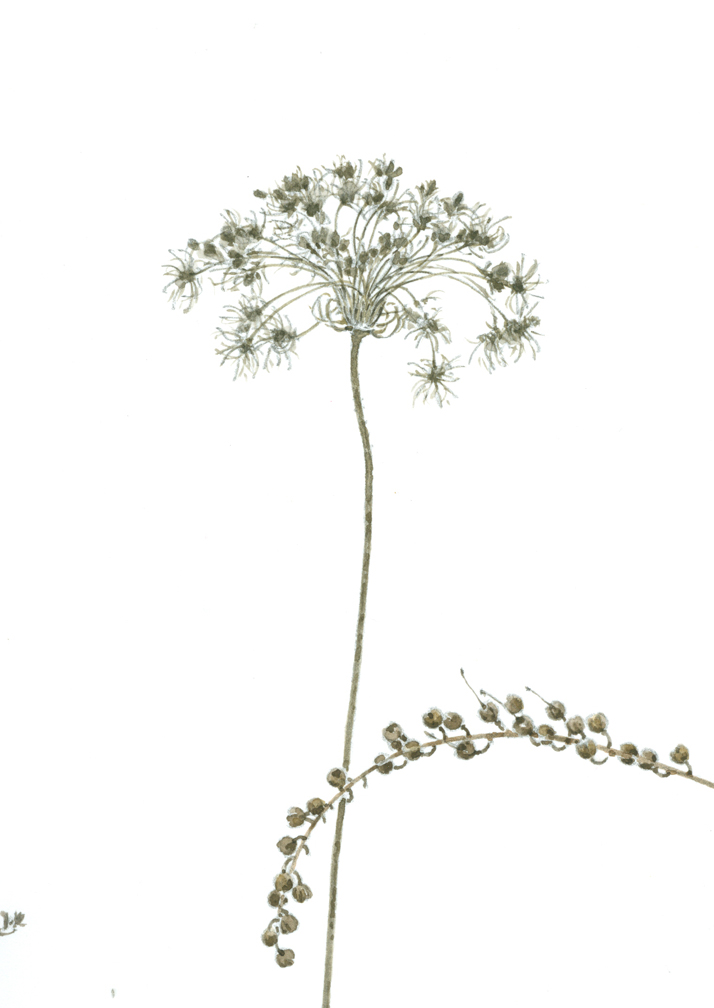

Seeds of Promise, watercolor on Arches hot-press, 21″ x 22.5″

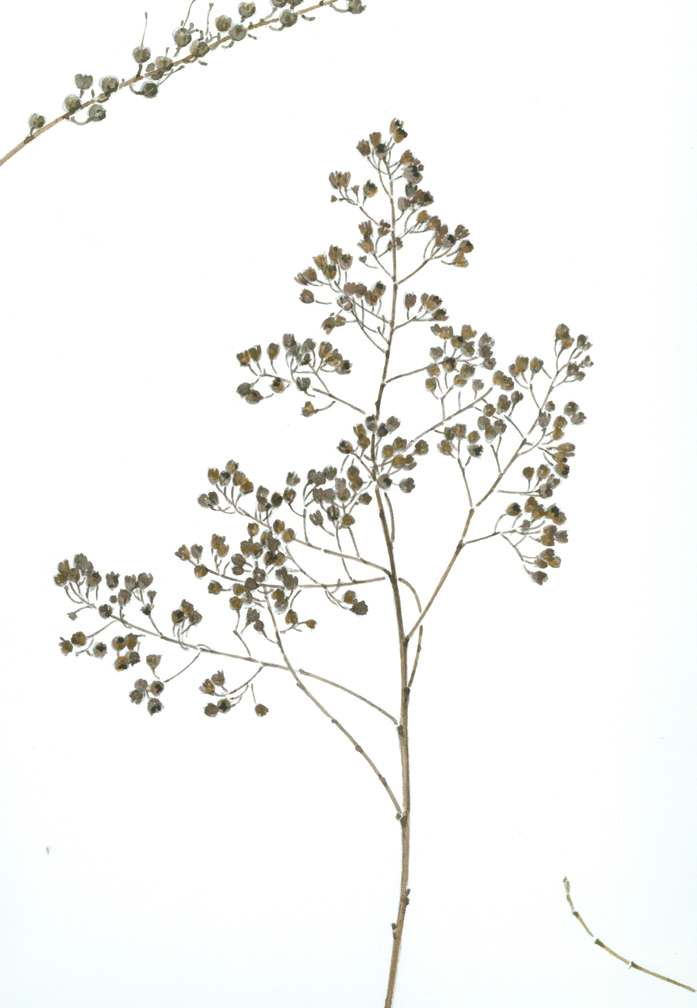

I have a pretty good idea what the various species are. I’ve got goldenrod, Queen Anne’s lace, an aster, sweet pepperbush and meadowsweet. Only one of the specimens has me puzzled: a tall, narrow spire with densely packed cylindrical seed capsules. I check my Newcomb’s and realize – of course! – it’s purple loosestrife. This is one species I’m sure the Audubon Society would have NO objection to my collecting! In fact, I had read on the visitor’s kiosk that the Society had successfully introduced a beetle into the wet meadow to control the spread of this invasive, non-native plant.

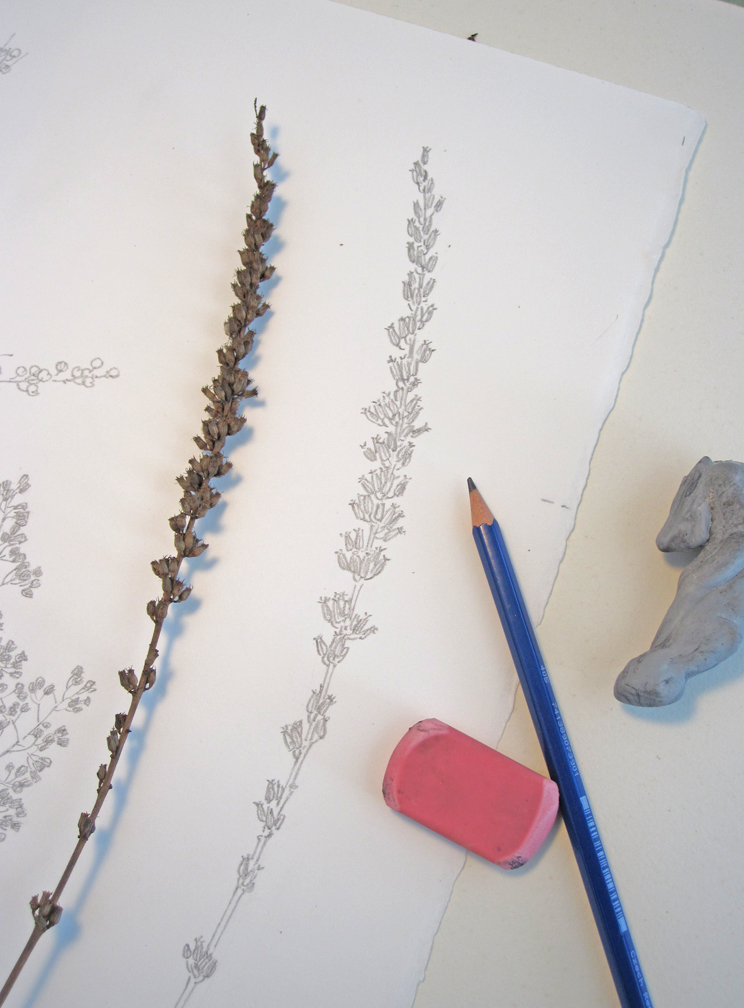

the drawing phase (purple loosetrife)…

After settling on an arrangement, I make a careful drawing of each specimen with a 2B pencil, working from the specimen itself. I call this approach “indoor field sketching”, since even though I’m not outside, I am working directly from life. I’m aiming for an accurate botanical portrait of each species, so draw carefully and slowly using a modified contour drawing technique.

detail: goldenrod and pepperbush

It’s amazing how much you can learn about botanical structure by working directly from specimens like this. For example, I noticed how the twigs of the pepperbush branched smoothly off the main stem without any obvious scars or marks at the junctions. Doing some research, I read that the new woody growth of pepperbush is forked or branched, and the side twigs do not always originate from a bud, as in most woody shrubs.

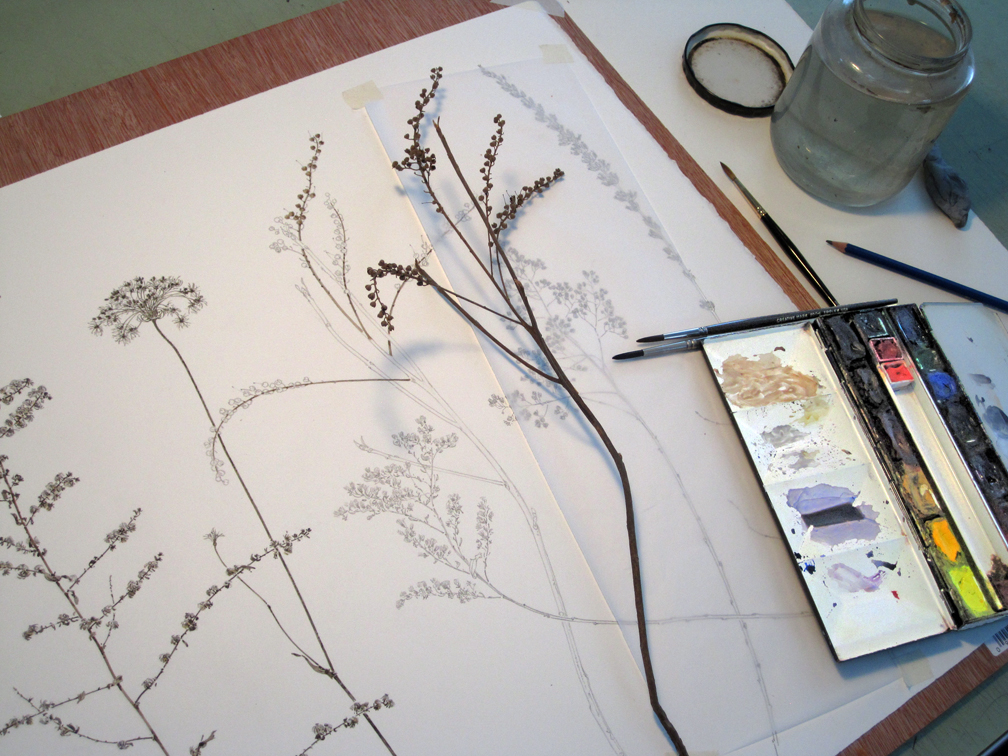

painting in progress…

I work from left to right in both the drawing and painting stages, so as to minimize smudging (I’m right-handed). I strive for accuracy but also a light touch, and I mix the subtle grays and browns with care, slightly emphasizing the color shifts. The attraction of this painting is really in the details, so here are some more close-ups:

calico aster

Queen Anne’s lace and pepperbush

meadowsweet

This is the largest watercolor that I’ve painted for the residency so far, at 21” x 22 ½”.

Seeds of Promise, watercolor on Arches hot-press, 21″ x 22.5″

I’ve probably spent more hours on this watercolor than any of the others, too. The painting and drawing took more than four full days of work. The original watercolor is currently on display at the Museum of American Bird Art in Canton, Massachusetts.