November 3 – 6, 2016

Sasachacha Heathlands Wildlife Sanctuary, Nantucket

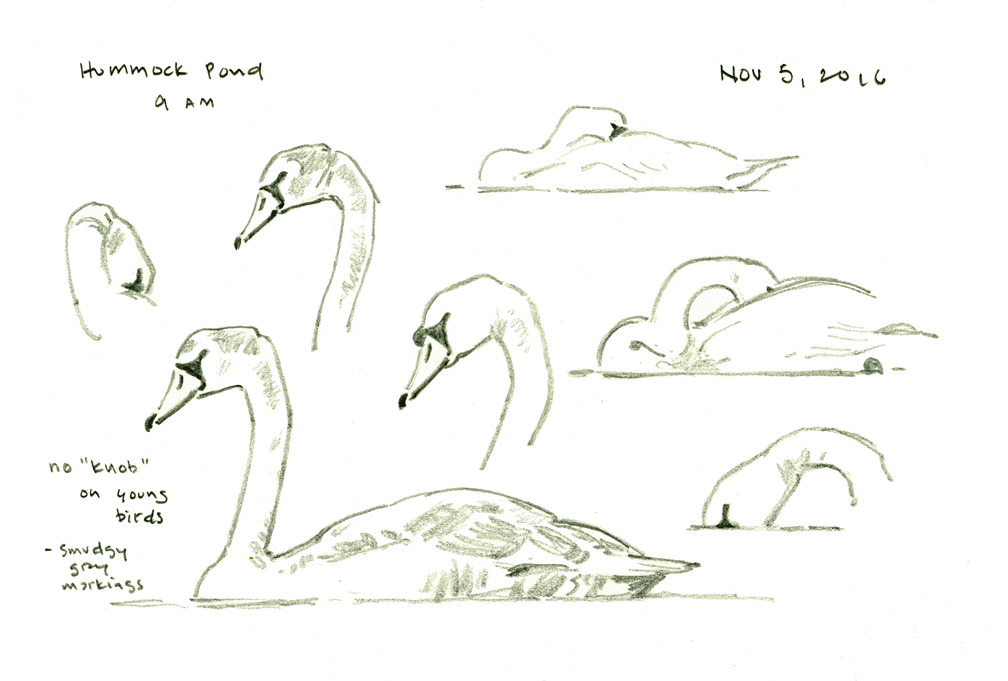

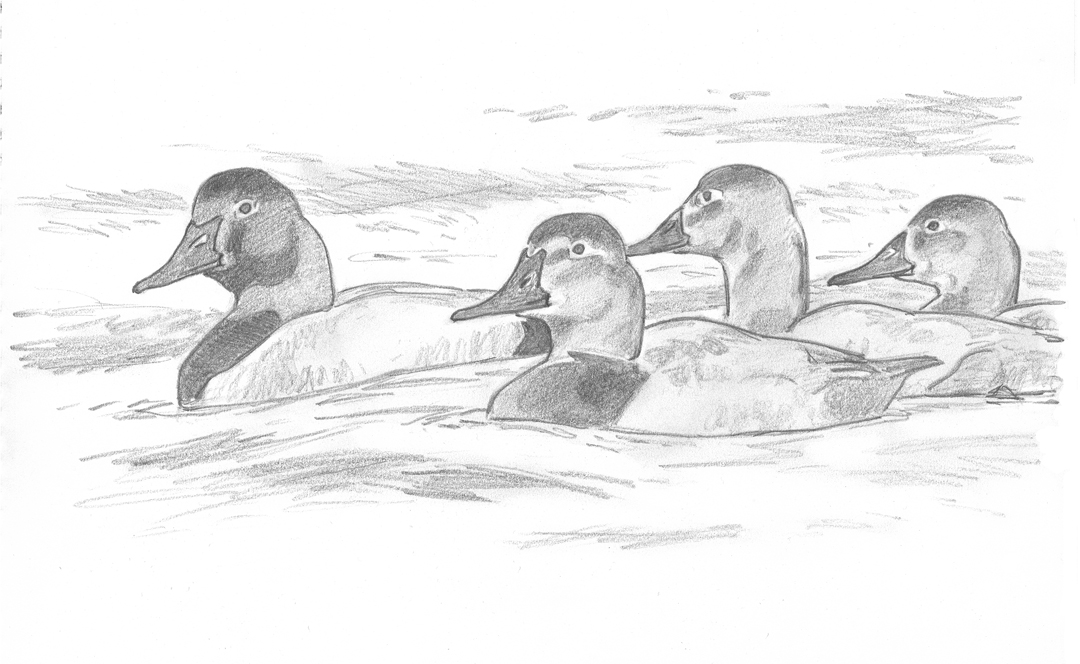

Canvasbacks pencil study, 10″ x 14″

Back in the studio, fresh from my visit to Nantucket, I make a pencil sketch of a group of canvasbacks, based on digital photos taken at Hummock Pond. I am contemplating various ways that I can convey the robust character of these ducks, when I remember a painting in a book I have about Bruno Liljefors, the noted Swedish animal painter. It’s an oil painting of Arctic Loons, painted in 1901.

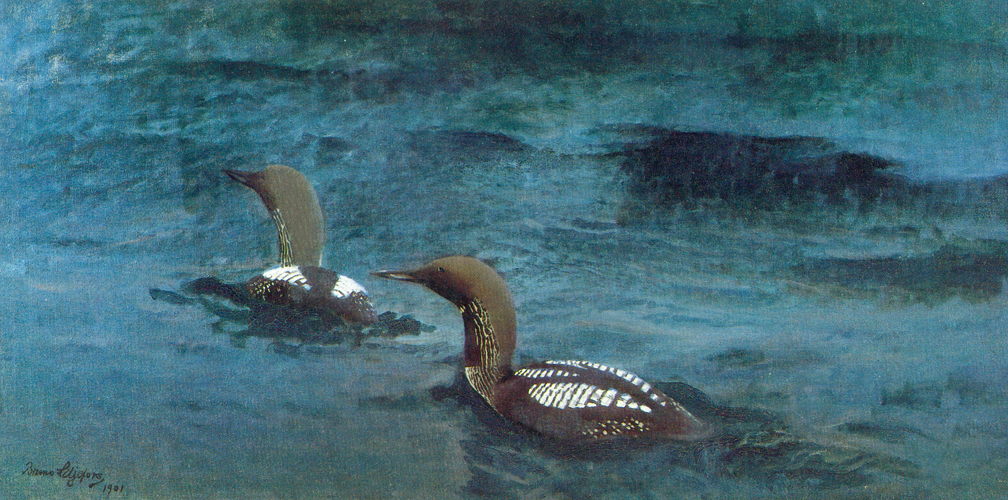

Arctic Loons by Bruno Liljefors, 1901

The color in the painting is rich and dark. The water, especially, is pitched in deep, saturated tones, so that the edges of the darkly colored loons are lost and found against the background – a very appealing effect!

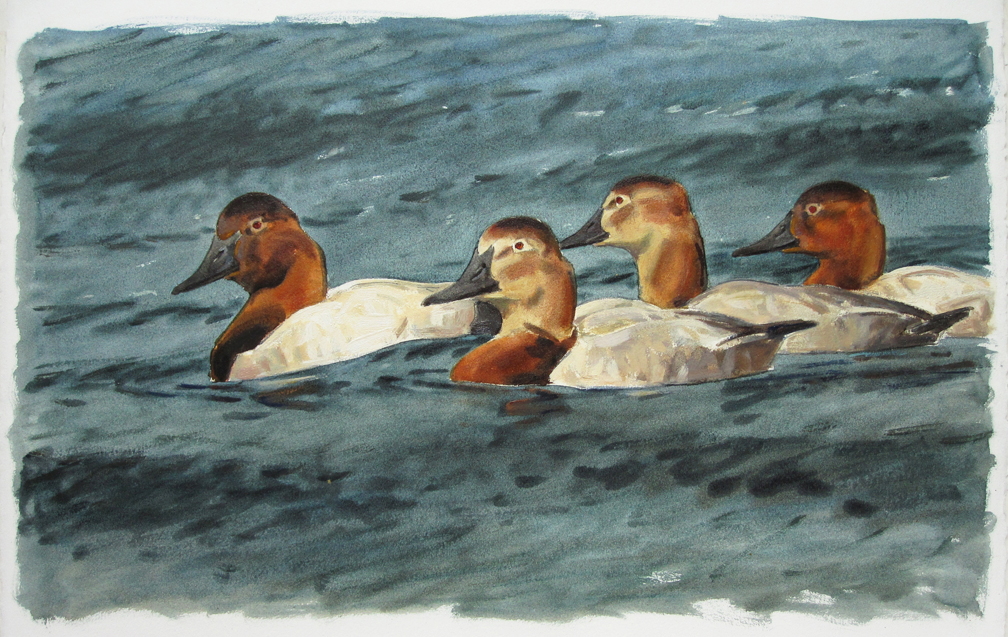

Several months ago, I had purchased some newly developed paper formulated for use with oil paints. Called Arches Huile, the paper looks and feels like ordinary 140 lb watercolor paper, but is ready for oil painting without any additional surface preparation. I thought the canvasbacks might be my opportunity to give this paper a try.

In my first session of painting, I put down a thin “turpy” wash of color, which soaks into the surface, but stays workable for a relatively long period.

STEP 1 – after the first “washes” of thinned oil paints

After an application of wet color, “open time” is that period in which the paint can be freely manipulated BEFORE the passage dries. Open time in watercolor is measured in minutes or seconds – a brief period due to the rapid drying time of the watercolor washes. Oil paints are the opposite, with a much longer period of open time. Hours, even days may pass before a passage of oil paint dries to the touch. This first session of working on the canvasback painting is like doing a watercolor in slow motion, and I have plenty of time to develop soft edges in the wet washes of color. After these first washes, I let the piece dry completely (which takes several days).

DETAIL of finished painting

Next, I build up the detail and the modeling of the birds with heavier, opaque passages of color. I decide to leave those first washes untouched in the background, since adding more layers of paint may destroy the sense of movement and that feeling of the wind riffling the surface of the water.

Canvasbacks at Hummock Pond, oil on Arches Huile paper, 15″ x 22.5″