November 3 – 6, 2016

Sasachacha Heathlands Wildlife Sanctuary, Nantucket

Although the official list of Mass Audubon Sanctuaries names only Sesachacha Heathlands, the Society actually owns three properties on Nantucket. Sesachacha Heathlands is the largest and most ecologically significant, but the other two properties are equally interesting.

My overnight accommodations are at Lost Farm Wildlife Sanctuary – a 90 acre tract that borders Hummock Pond and features an extensive pitch pine forest. Mass Audubon’s smallest property on Nantucket is a 30 acre parcel at Smith’s Point near Madaket.

On my first day, Ernie Steinauer, Mass Audubon’s director of sanctuaries on Nantucket, gives me a tour of the Smith’s Point property, and then shows me some extensive areas of sandplain grassland at Medaket and Miacomet Plains.

Sandplain Grassland

Like coastal heath, New England sandplain grassland is an extremely rare and localized natural community, and the best remaining examples in the world are on Nantucket.

The Crooked House

The Smith’s Point property was once owned by Mr. Rogers of television fame. His house, which he named “The Crooked House” and often referred to on his show, is at the edge of the reserve. I chuckled when I noticed that the sign on the house is also mounted crooked (Fred Rogers had a good sense of humor!)

I soon realized that the landmass of Nantucket exists very much at the whim of wind and waves. The section of Madaket Beach at the base of Smith’s Point is rapidly being buried in sand, as a big dune marches over the area. In the front yard of this cottage (just a few doors away from Mr. Roger’s Crooked House), a split rail fence is nearly buried, with only the tops of the fence posts still visible above the sand.

Inundation at Madaket

Elsewhere on the island, property owners are plagued with the opposite problem: EROSION. Later in my stay, I visited Siasconset on the south shore, where homes along the top of a 100 ft. bluff are watching their backyards crumbling into the sea at an alarming rate – some losing as much as 30 feet of property in a single winter storm.

Erosion at Siasconset

Contractors are busy moving several homes back from the edge of the bluff, and a neighborhood association is scrambling to find ways of slowing the erosion.

Ernie had made arrangements with two eminent Nantucket birders to continue my orientation tour, and I meet up with Edie Ray and Ginger Andrews at mid-day. Their expert guidance familiarizes me with the best routes and vantage points, and furnishes a deeper understanding of both Nantucket’s natural history, and the challenges involved in protecting the remaining natural areas.

Although early inhabitants viewed the expansive coastal heaths in the center of the island as a desolate wasteland, today this area is recognized as a “globally rare community”, with the Nantucket Heath representing the best remaining example in the world. Mass Audubon’s Sesachacha Heathlands sanctuary preserves more than 800 acres of this unique habitat.

The reserve can be accessed by navigating a maze of crude sand tracks, and Edie and Ginger show me how to find the two highest points in the moors. From the summits of these hills, I can take in the expanse of the heath, rolling away in all directions.

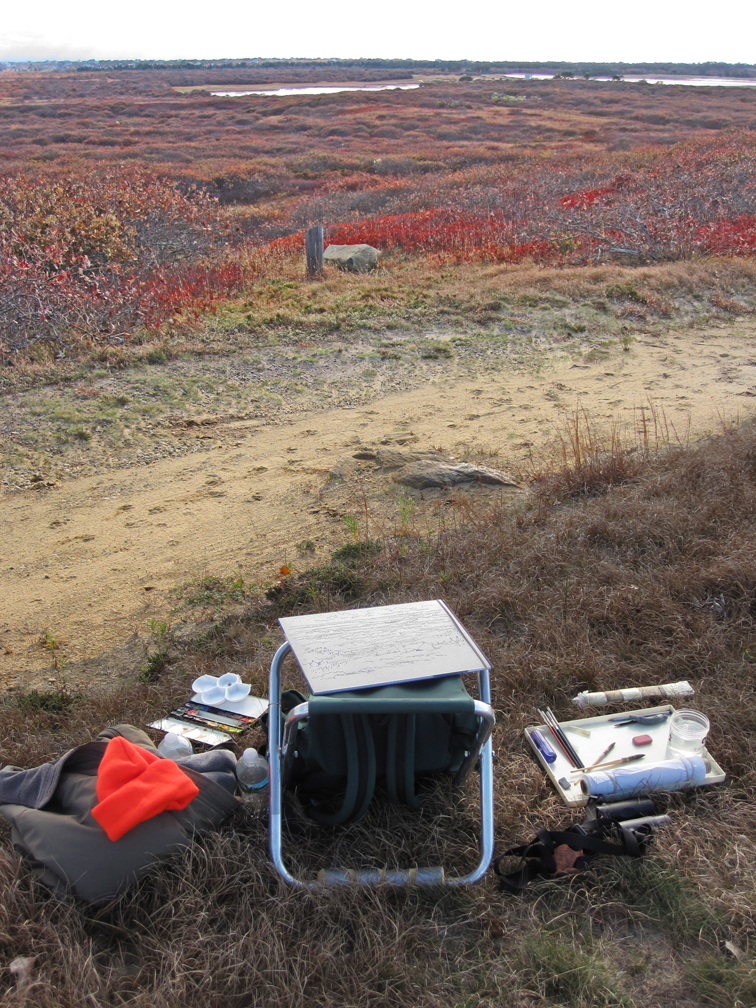

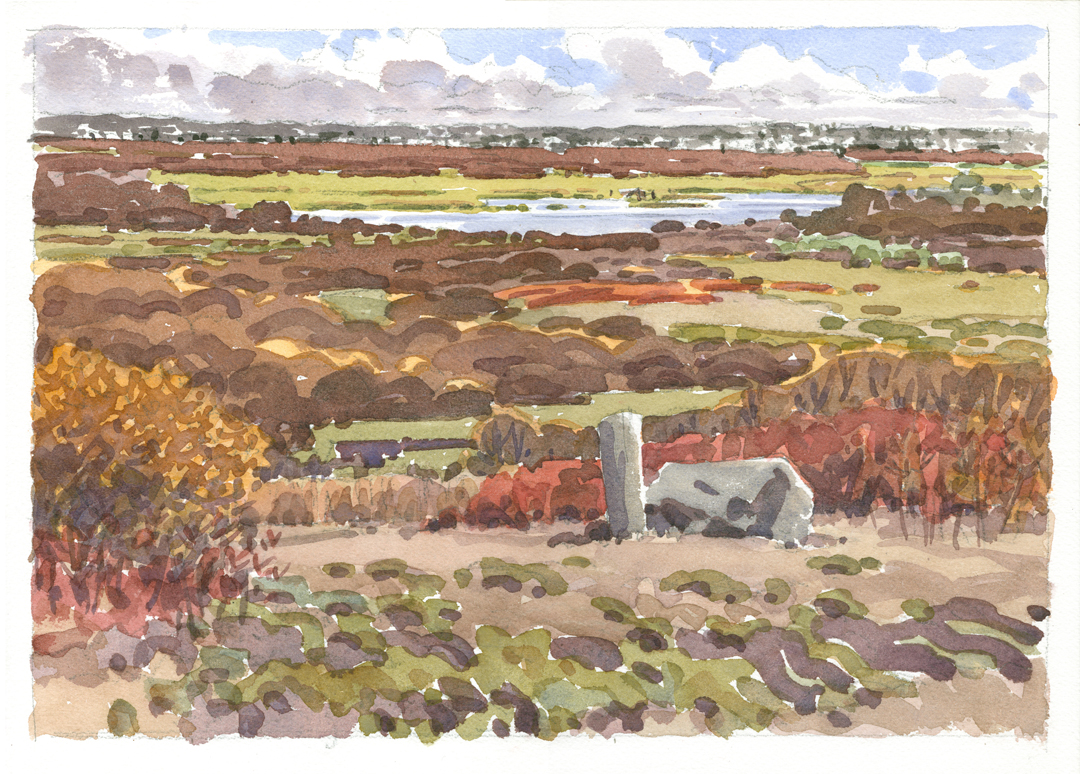

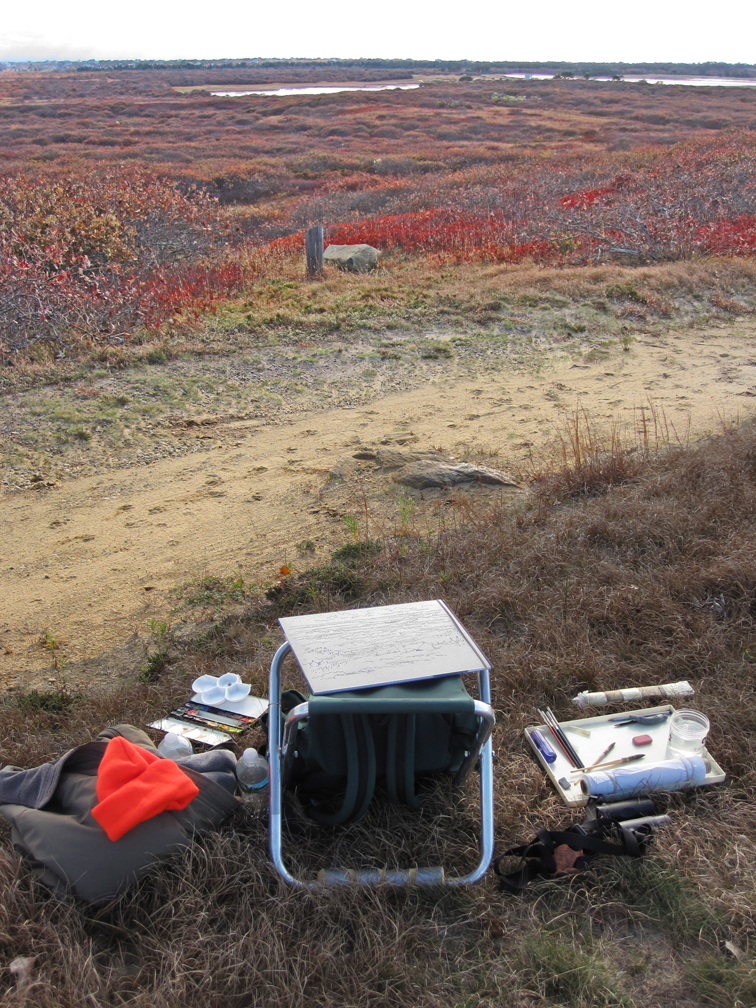

Set-up at Quarter Mile Hill

I find my way back to Quarter Mile Hill the next day in Mass Audubon’s well-used Isuzu Rodeo, and set up to paint a landscape. The view south takes in the sparkling waters of a large cranberry bog nestled in the distant hills, and in the foreground is a varied mosaic of heath vegetation. Also in the foreground is an old post next to a boulder (uncommon items in the moors). These supply both a sense of scale and a center of interest for my painting. The autumn colors are slightly past their peak, and mauve and rust tones predominate – they’ll be a challenge for my watercolor palette! (I carried the orange hat as a precaution – deer hunting season is in full swing!)

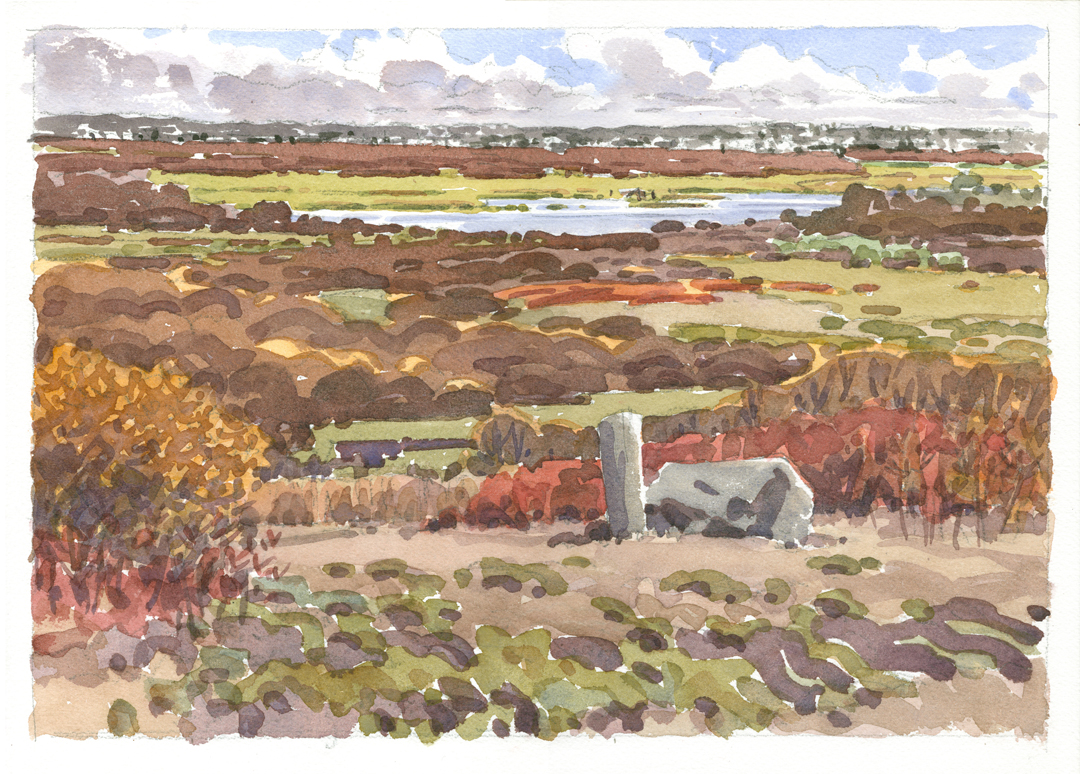

The View from Quarter Mile Hill, watercolor on Arches cold-press, 10.25″ x 14.25″

I have, by necessity, stylized the heath vegetation in my watercolor, but anyone familiar with the botany of the heath should be able to pick out the dominant plants. In the near foreground is a mix of bearberry and false heather: low-growing shrubs that form a dense groundcover. The bright red patches are huckleberry, and the masses of purplish brown are scrub oak. You might also pick out a patch of little bluestem grass in the middle ground, and a distant patch of high tide bush – showing mint-green in the distant right. Another big swath of scrub oak spans the ground beyond the bog, and in the distance are the developed areas of the south shore.

Bearberry and False Heather

I painted a related watercolor back in my studio. I wanted to create another composition that emphasized the gently rounded shapes of the moors, and by introducing one of the sand tracks, I could lead the eye into the scene and help define the rolling topography.

Sand Track in the Moors, watercolor on Arches rough, 8″ x 12.25″

I had seen a merlin an hour earlier at nearby Sesachacha Pond, and introducing it into my scene for a sense of movement.