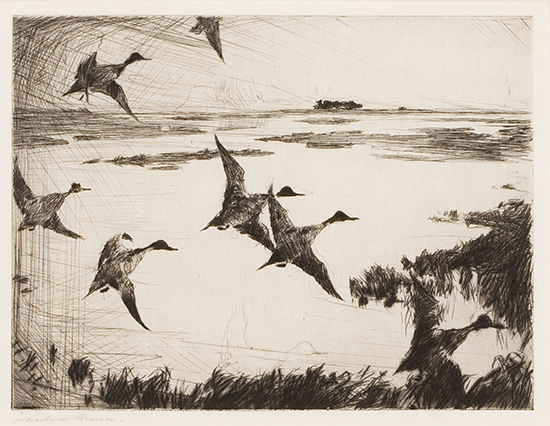

Frank Benson, a giant of the Boston School of Impressionist painting, is also the standard bearer of modern sporting art in the United States. Fellow printmaker John Taylor Arms wrote that Benson “has achieved the distinction of founding a school—that of the modern sporting artist. In this, his followers and imitators have been many, his equals none.”

Left: The Duck Marsh by Frank W. Benson, oil on canvas, 1921. Mass Audubon Collection, gift of Agnes S. Bristol, 1972. Used as the frontispiece for John C. Phillips’ A Natural History of the Ducks, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1922.

But his second career as a printmaker specializing in sporting material would not begin until he reached middle age. Born in Salem, Massachusetts in 1862, Benson spent his early years studying at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and at the Académie Julien in Paris. In 1889, after a few years of travelling and holding various teaching posts, Benson began his long tenure as a teacher at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. During these years his stature as an artist constantly grew and he accrued numerous awards and commissions.

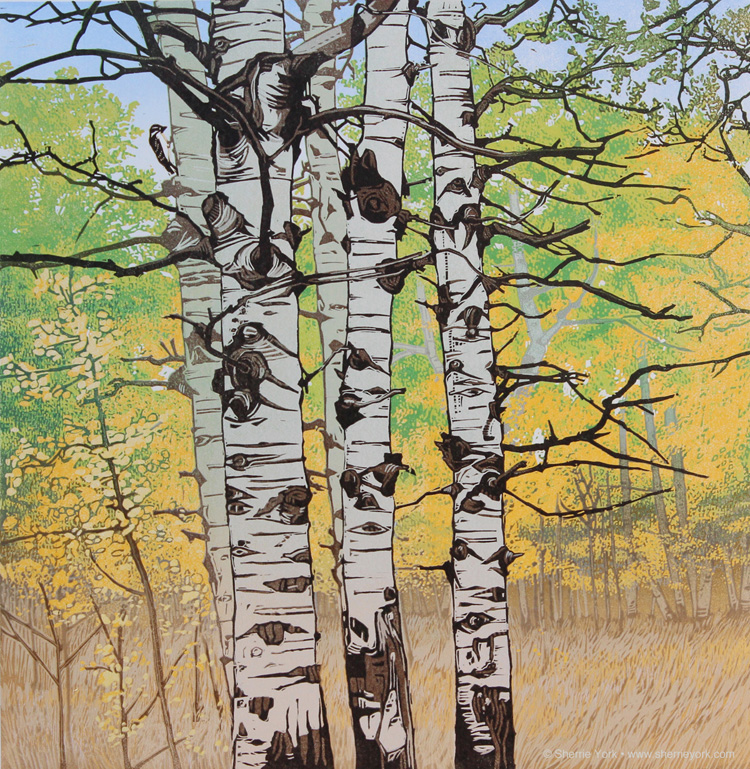

Using family members as his primary models, Benson bathed them in a diffused atmospheric light. These paintings show the artist’s early interest in Impressionist plein air scenes of leisure, realized through broken brushstrokes and a light-infused palette. As with many of the American Impressionist artists of the period, he acknowledged the complete dissolution of the figure as seen in French Impressionism, but never lost his interest in a composition grounded in realism and structure.

Benson left his teaching position at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in 1913—coincidentally the same year that the Armory Show in New York shook up the art world and formally ushered in the new style of Modernism.

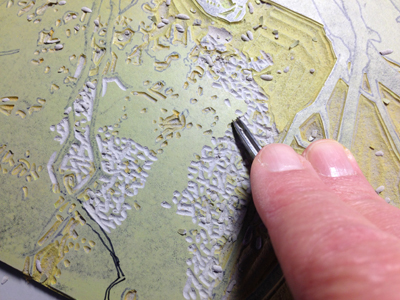

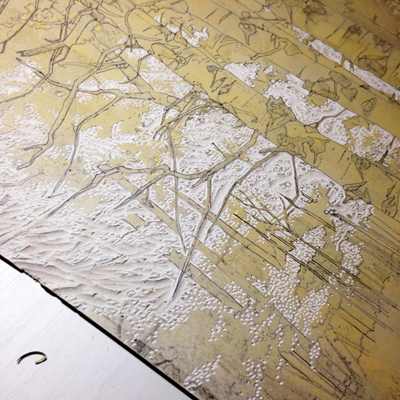

Soon after leaving teaching behind, Benson started his career as a printmaker specializing in sporting material. Interested in ornithological illustration since he was a boy, Benson brought to his prints a love of nature and the outdoors as well as the “nurturing” experiences of a classically trained artist.

These prints also incorporate his interest in Modernism. In his spare, understated handling of the scenes, the birds—always identifiable—are depicted as calligraphic accents in elegant, almost abstract, compositions. In 1915 Benson had his first exhibition of sporting prints, and they were immediately in demand.

I’ve had the opportunity to handle the sale and marketing of numerous paintings, prints and watercolors by Benson. I greatly appreciate his tour de force Impressionist paintings, but I find the sporting prints very compelling as well. They have a timeless appeal to past and present collectors alike.

SUPPORT OUR WORK and Donate to the Museum of American Bird Art

Our guest blogger Colleene Fesko is a Boston-based fine art and antiques appraiser and broker, and a friend of MABA. She is frequently seen on the hit PBS television series Antiques Roadshow.