May 31 to June 5, 2020 marked the first ever Black Birders Week, a five-day virtual event to raise awareness and highlight the need for action surrounding the racism and discrimination Black individuals face in nature spaces. Unlike their white counterparts, black individuals face additional challenges that can prevent full enjoyment of the outdoors; challenges that are rooted in systemic and historical racism that manifests today in unconscious and conscious biases against black individuals. These challenges often result in low representations or exclusion of people of color in nature and outdoor activities. Black Birders Week sparked a national discussion and the organizers, a group called the BlackAFinSTEM collective, hope that the result of this increased awareness and understanding of the black perspective will lead to a normalization of people of color in birding, nature, and science.

The idea for the five-day-long virtual event was conceived in response to the alarming racist incident recorded in Central Park between Christian Cooper, an avid Black birdwatcher and member of New York City Audubon board of directors, and a white woman who was weaponizing race as a scare tactic against Cooper. Seeing the national response, organizers saw this as an opportunity to acknowledge that the experience of Christian Cooper was not uncommon for Black people in nature, and although racism manifests itself in various ways, there are things everyone can do to support a more diverse and welcoming outdoor community for all.

Each day of the event had a different online experience. Below are posts from Twitter and Facebook that highlights the week’s activities and participants experience.

Day 1: #BlackInNature celebrated Black nature enthusiasts around the world debunking the stereotype that black people do not enjoy nature.

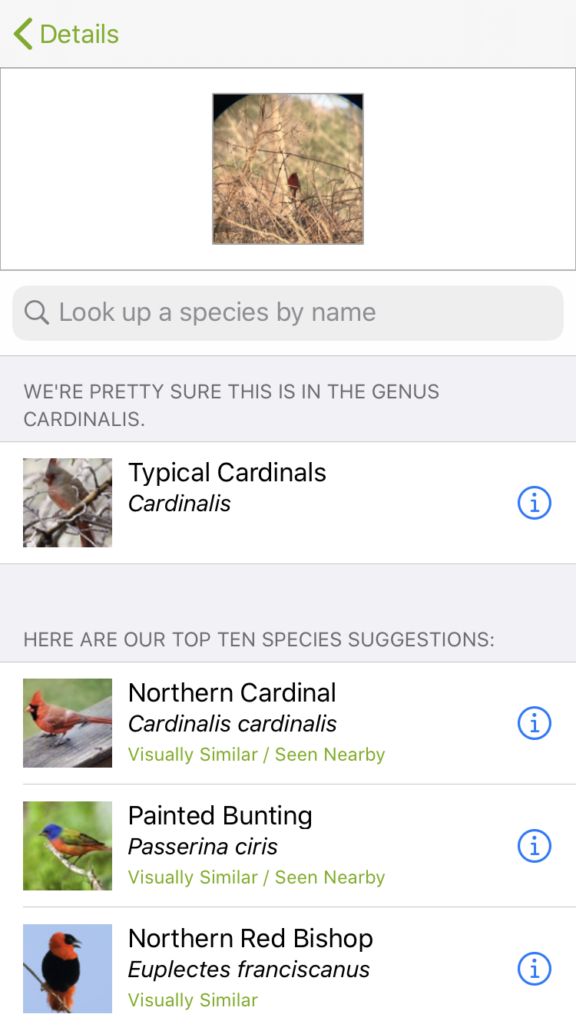

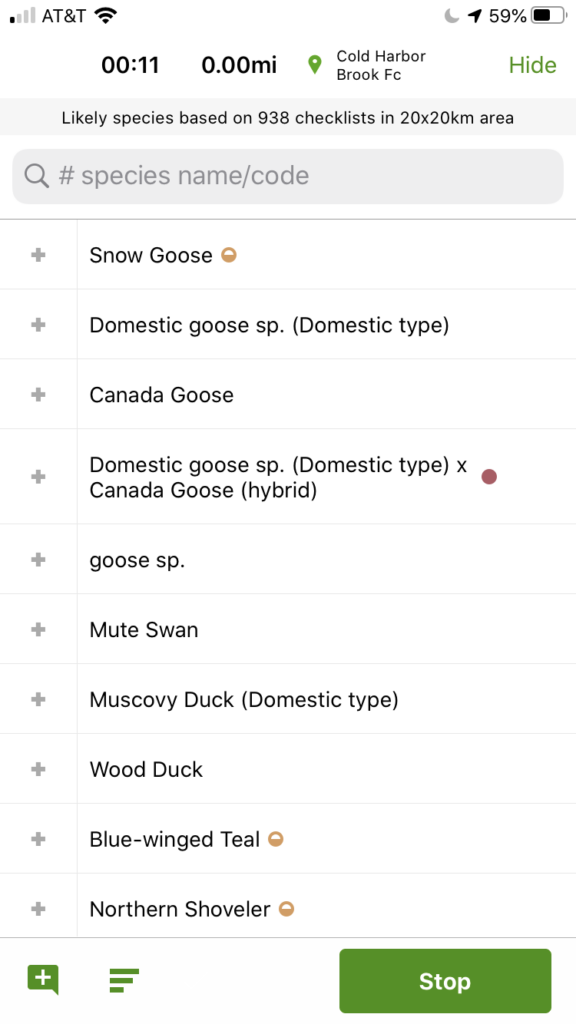

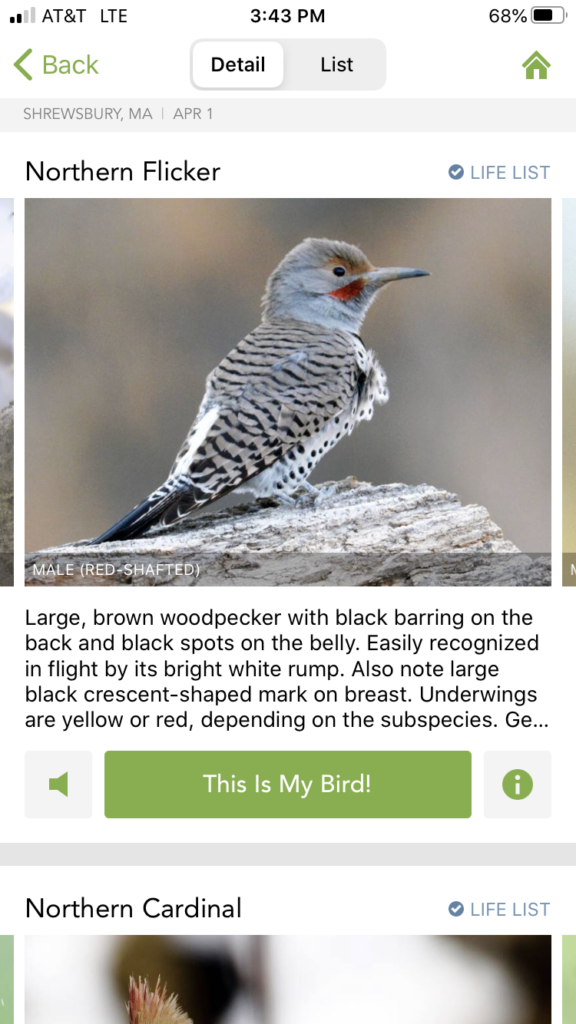

Day 2: The #PostaBird challenge asked people to share their favorite bird photos and facts.

Day 3: #AskABlackBirder featured a two-hour Q&A with Black Birders

Day 4: The #BirdingWhileBlack livestream discussions offered a space for Black birders, including Dr. J. Drew Lanham, Jason and Jeffrey Ward, Corina Newsome, and Kassandra Ford, to share their love for birds and their experiences—both positive and negative—being and working in natural spaces. (view Session 1 and Session 2).

Day 5: #BlackWomenWhoBird increased visibility and representation.

Key takeaway from Black Birders Week

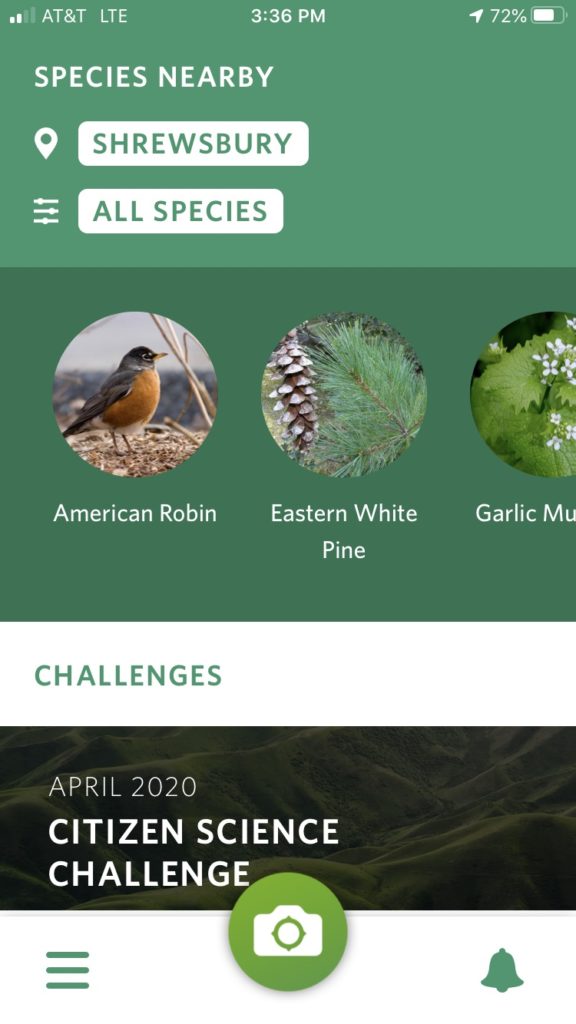

Birding and Nature are for Everyone, Everywhere

Birding and being in nature are typically thought to be rejuvenating, fun, relaxing, and peaceful, but people of color cannot always fully enjoy these feelings because of an underlying sense of “otherness” or not belonging. In some cases, they experience racism both blatant and subtle. The livestream sessions with Black birders were particularly eye-opening because each and every person on the stream could recount a time where they:

- Felt unsafe going to a certain area (or even an entire state) to bird because they feared someone would report a “suspicious” black person or their safety would be otherwise threatened because of the color of their skin.

- Felt out of place in a group of other birdwatchers because they were the only person of color and the others in the group seemed amazed by them being there.

- Experienced outright racism from police or other individuals.

- Made sure to be obvious that they were birdwatching by raising their binoculars or wearing nerdy bird-themed clothes to reduce suspicion.

It is unacceptable that this is a reality for so many bird and nature enthusiasts. Birds and nature are for everyone to enjoy and study regardless of the color of their skin.

You Can Make A Difference

Learn more about the discrimination and racism people of color face when they are in natural spaces, at science conferences, and in their lives.