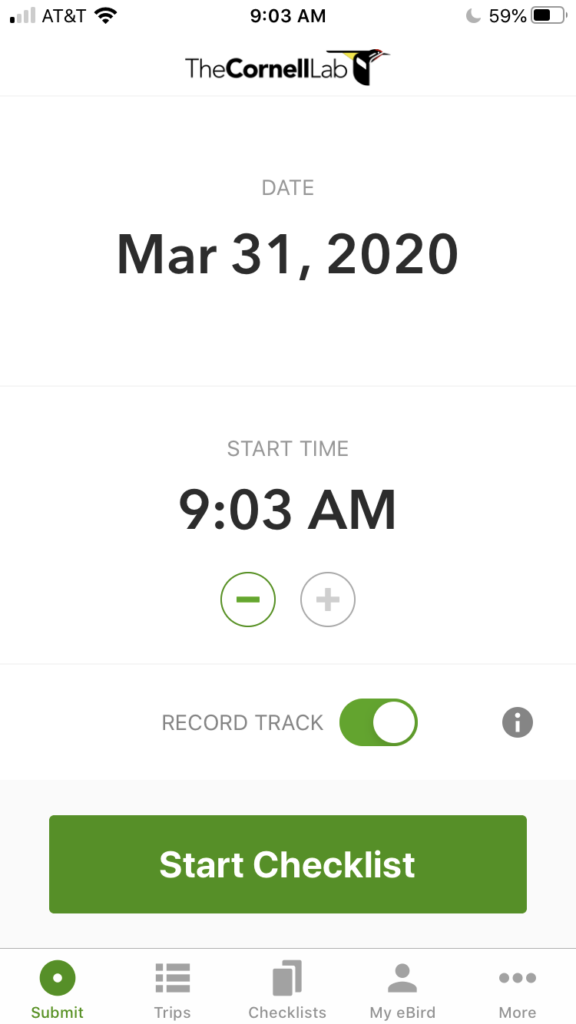

Warblers seemed to rain from the sky during Bird-a-thon 2020 after unusual weather doused Massachusetts in migrants. Birder participation more than doubled, too, but not because conditions predicted a massive influx of birds. Instead, it seems that more beginners were brought in by a family-friendly approach and a focus on birding from home.

Birds were everywhere

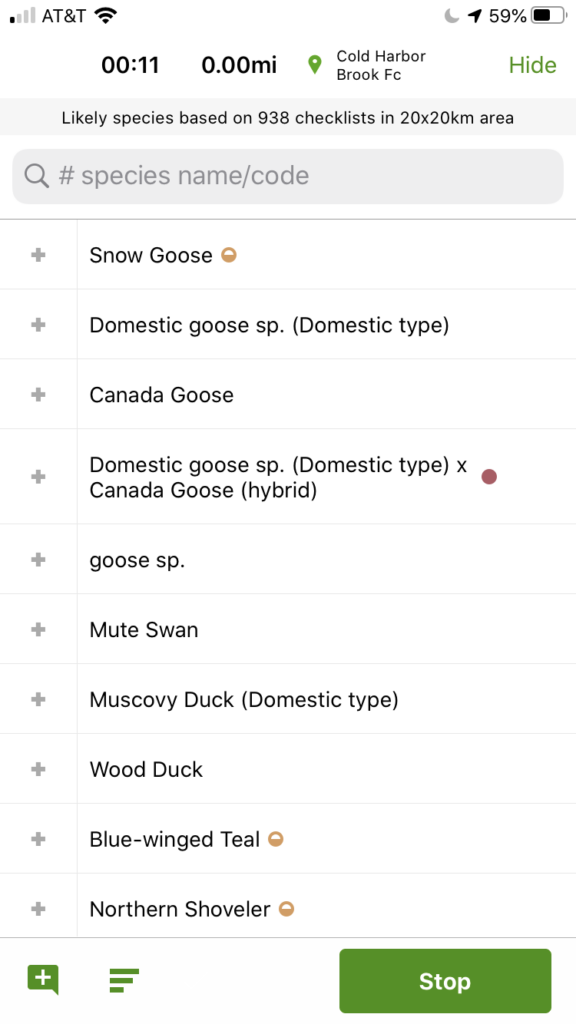

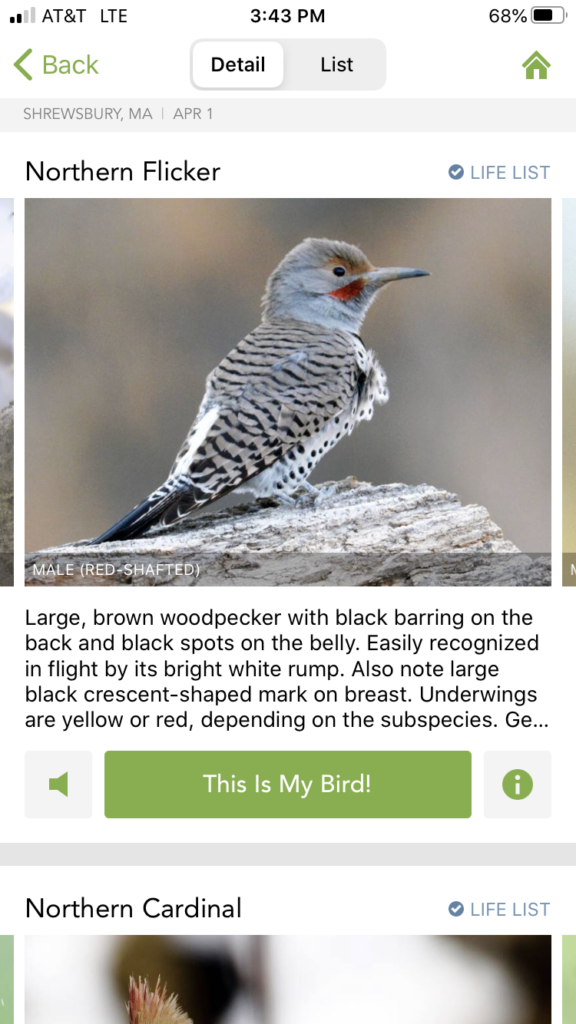

As the sun rose on the Outer Cape on May 16th, thousands of birds gathered in the dunes after being blown in from the southwest and grounded by rain. The subsequent dawn flight became the subject of several expert articles, including an in-depth analysis of the conditions by ornithology professor Sean Williams. Some eBird checklists recorded over 100 Bay-breasted and Cape May Warblers, plus dozens of individuals of other uncommon migrants like White-crowned and Lincoln’s Sparrows.

Inland, the action was almost as good, with several Bird-a-thon-ers in dense suburbs and towns setting personal records for their yards. Nonstop north winds had held birds back for nearly two weeks, and when the wind finally turned southwest, restless migrants pushed ahead despite the storms. Nearly everything showed up at once; yard reports of Cerulean Warblers, Bay-breasted Warblers, and Bobolinks highlighted the strength of the previous night’s migration.

Canada Warbler: Gunn Photography

Wilson’s Warbler: Ben Griffith

“Fallout” may be an overused term– but this was real

The word “fallout” often gets misapplied to any day with really good migration. In reality, even in the loosest sense, this word refers to exhausted migrants that land in adverse weather. In the strict sense, it describes a stream of migrants that are knocked down by fast-moving storms, landing en masse when they meet the edge of the weather front.

In this case, adverse weather formed well before nightfall, but the long-delayed migrants pushed ahead anyway—there was no “knockdown” effect from the edge of a front, but the wind and rain did exhaust many birds that were blown east into Massachusetts. So, yes, this was a fallout, loosely speaking—and a uniquely great birding day by any stretch of the imagination.

Drawing: Cameron Piper

Kid’s Craft: Christine Whitebread

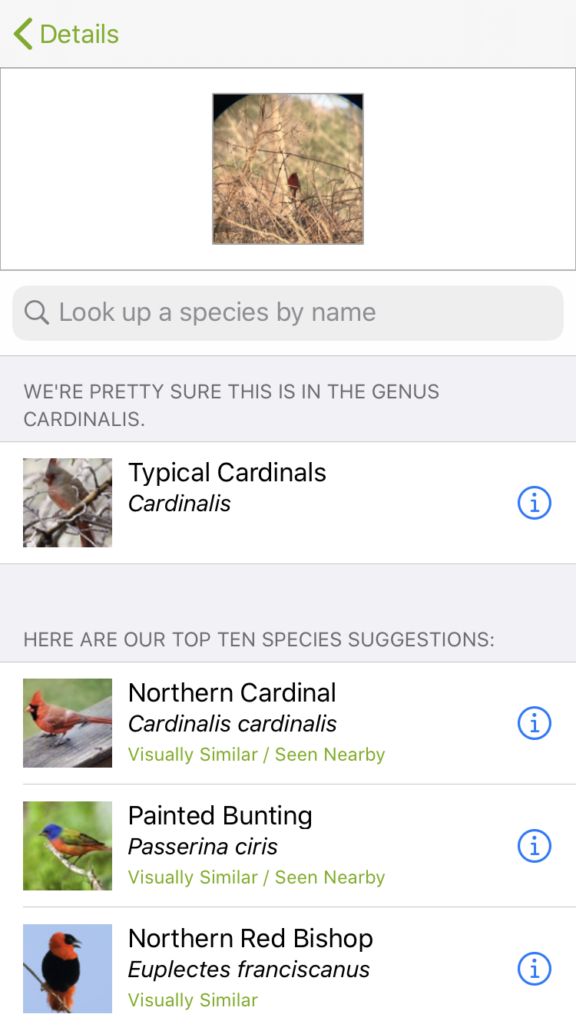

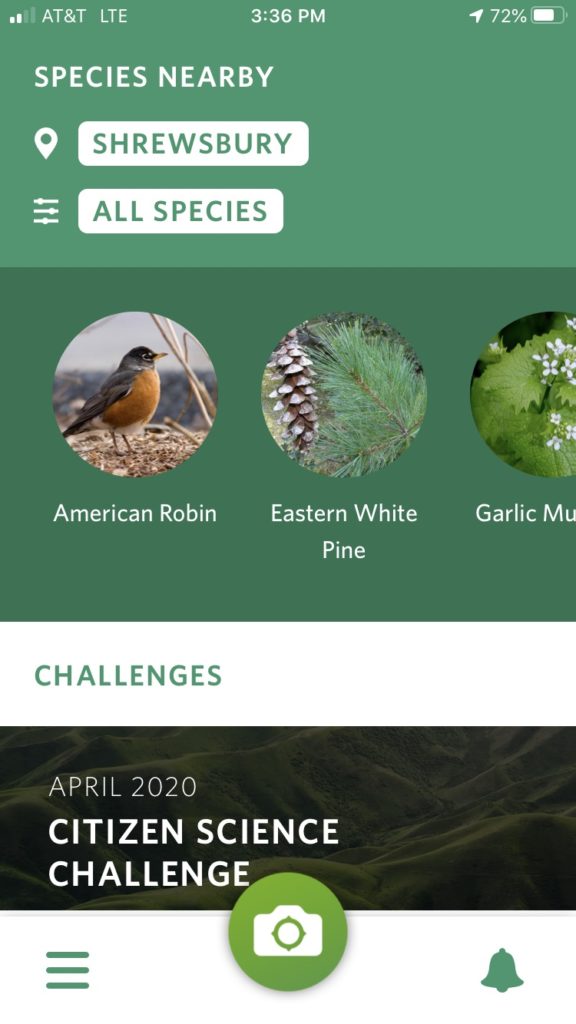

New birders drove up participation

A normally competitive endeavor, this year’s Bird-a-thon focused on participation.The team cap was lifted, and new activities were made up to engage kids and non-bird enthusiasts in earning points for their team, like inventing silly bird names and creating bird art. With a stay-at-home order driving a surge in interest in birding, it was important to welcome new enthusiasts to the fold– and avoid encouraging birders to tear across the state in search of rare species. Subsequently, Bird-a-thon attracted 1,600 participants this year, more than double the 750 who took part in 2019.

Eastern Bluebird feeding young

Renata Gilarova sporting protective face gear

Donations were up, too

As of right now, Bird-a-thon raised over $295,000 – far surpassing the $250,000 goal. Despite the current economic hardships of the coronavirus pandemic, these funds are up from the $240,000 raised last year.

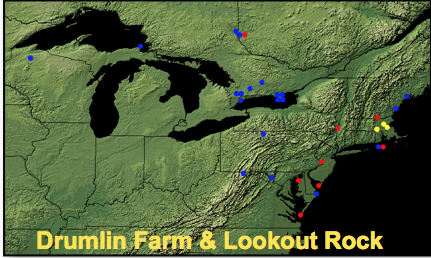

The final tally

In total, Mass Audubon teams saw 242 unique species in Massachusetts. Teams were awarded points based on the number of unique bird species the team saw plus the number of nature-based activities team members completed. Drumlin Farm took first place with 992 points and a team of 230 participants (including 90 kids), earning the “Eagle Eye Award.” Second place, for the “Home Habitat Award” went to Wellfleet Bay with 537 points. The team from Ipswich River took home the award for the highest number of species seen: 206.

For a full recap of the incredible birding day participants shared, check out local birder and documentarian Shawn Carey’s video on the experience, complete with teammate interviews and great bird footage.