(This is the final installment in a series on birding by radar. Read the first and second post first so this one makes sense!)

On May 20, 2017, Bay-breasted Warblers seemed to drip from every tree at Mass Audubon’s Marblehead Neck Wildlife Sanctuary. Birders tallied dozens of this normally scarce migrant practically on arrival, alongside equally impressive numbers of Canada Warblers, Blackburnian Warblers, and other migrants. The air filled with high-pitched warbler songs so much that it was difficult to distinguish one from the next. Plum Island was equally loaded, with some observers tallying 123 species for the day. Was this a fallout, or just an excellent day for migration?

Fallout is one of the most exciting spectacles a birder can hope to experience in migration. Serious birders mistakenly use this term all the time to mean “a lot of migrants in one area,” but fallout refers to a very specific phenomenon: birds that cut short their migratory journey due to severe weather or exhaustion.

Birds will fall out along the coast if they are blown far off course over the ocean; they return to land hungry and tired, and large numbers feed at ground-level in coastal vegetation. Fast-moving fronts of severe weather can also cause fallouts when they interrupt bands of migrating birds, and stationary fronts can stall migrants that land when they encounter it and build up along its edge.

On May 20th, 2017, birders who read the radar saw that northeastern Massachusetts experienced a borderline fallout; a storm had blown birds against the coast and over the ocean, but the weather cleared early enough that many grounded birds continued migrating afterwards. Regardless, the superb birding that day was undeniably predictable.

Reading the Radar on May 20, 2017

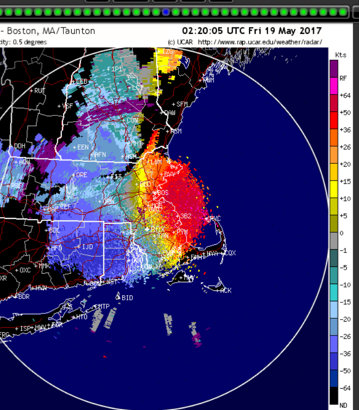

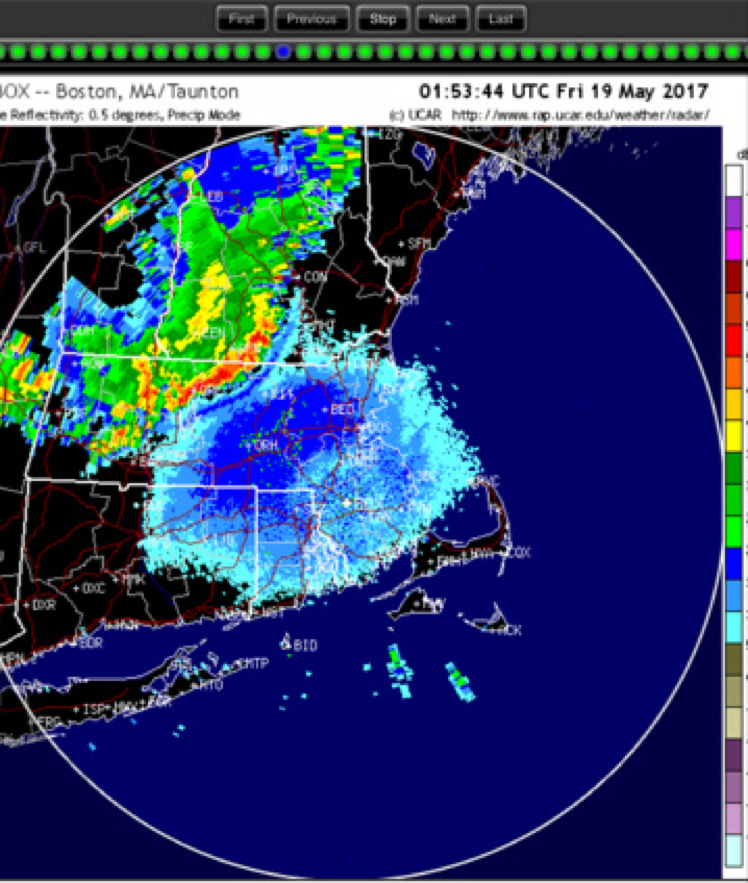

The radar for this night showed moderate migration, with a front of severe weather pushing birds south and east. The dense (green and red) precipitation is pictured up against a group of birds, represented by the blue line between the edge of the storm and the mass of birds in the center of the frame.

As the front moved east (see below), the density of migrants increased just to its south. The birds at the edge of the storm, pictured in blue above, appear to have been pushed into the main mass of birds, where they show up as a streak of green (higher-density) in the image below.

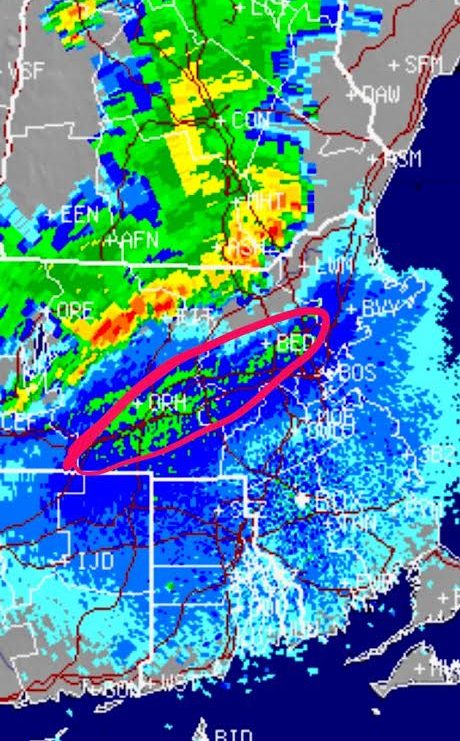

The velocity map below paints a slightly different picture. The black areas between the storm and the birds show that the storm is grounding birds. But the birds just away from the edge—that red spur in New Hampshire, for example—are not getting pushed south by it.

The red color (that is, increased relative velocity reading) of that patch of birds shows that they are either 1) continuing to fly east but increasing their speed or 2) flying north instead of east, as if to go around the storm, and maintaining their speed. In either case, the fact that these birds are being detected further away from the station than the rest of the cluster indicates that they increased their flying altitude (recall that the further away birds are from the station, the higher they need to be to show up on the radar). It’s anybody’s guess why they would be doing this; the storm exists at a higher altitude than the birds, so flying up into it seems counterintuitive.

What Was Missing

Since the front passed fairly early in the evening, many migrants had a chance to pick themselves up and move along after the storm passed. It is not a reach to imagine that the birds that built up along the edge of the storm took off again after the storm passed, and moved northeast again, landing in similar areas along the Maine coast.

What Looked Promising

Storm or no storm, a forecast of west winds turning northwest at dawn is always a good sign for coastal sites. West winds blow inland migrants against the coast, where many prefer to land instead of flying over the water. Other birds overshoot the coast in strong winds, and when winds turn northwest at dawn, these ambitious flyers drop back in at coastal sites like Plum Island and Marblehead Neck.

The Results

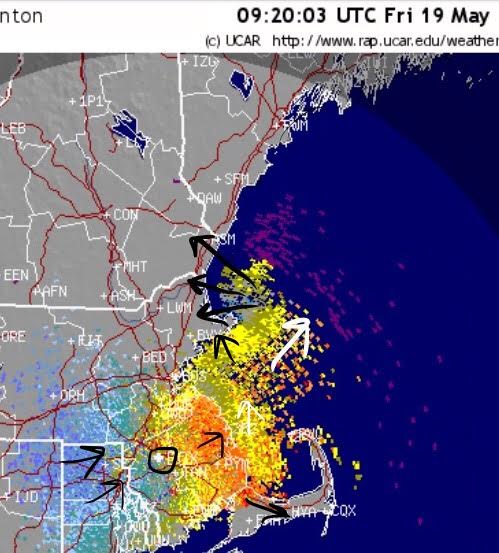

A small but significant stream of birds poured off the ocean and onto the coast in the morning. Some experts say that this was strictly because they were pushed east by the storm, but some hold that these birds would have overshot the coast with the west wind anyway. In either case, velocity readings from early (4:30-5:30) the next morning show many birds over the ocean colored in yellows, olives, and some blue: birds that are not moving directly away from or directly towards the radar station. In some areas, this means they were moving towards the coast.

Arrows on this map indicating bird direction were determined by drawing a line from the radar station (circled) out to a point with birds, and then drawing an arrow slightly over 90 degrees to this line for birds moving slightly away from the station (yellow).

Likewise, the arrow would be at exactly 90 degrees to the line for birds moving neither towards nor away from the station, slightly under 90 degrees to the line for birds moving slightly towards the station (light blues and greys) and in the direction (or close to it) of the line for birds moving strongly towards or away from the station (colored red or deep blue). If you didn’t follow this, don’t worry: the key is that birds over the water at dawn often means coastal fallout.

To sum it up, there were three elements of that evening’s radar that practically screamed “Go birding on the coast tomorrow”:

- Radar showing many birds moving more east than north, and some shooting over the coast at high speed

- A strong storm that could force migrants against the coast even more vigorously than the winds could, and might even ground many of them.

- Most importantly, birds coming in off the ocean early in the morning (4:30-5:30).

Lo and behold, it was an incredible day on the coast the following morning, even though arguments over how much the early-evening storm had to do with it remain unresolved.

This is just one example of how reading the radar can lead to better birding. Try it for yourself this spring and see if you strike spring migrant gold!