While many of us are stuck at home, opportunities to explore nature are more limited. However, there are many ways to engage with nature from your phone or computer, from sharpening your ID skills to submitting observations to a citizen science project. Below are five apps that will keep naturalists and non-naturalists engaged and excited.

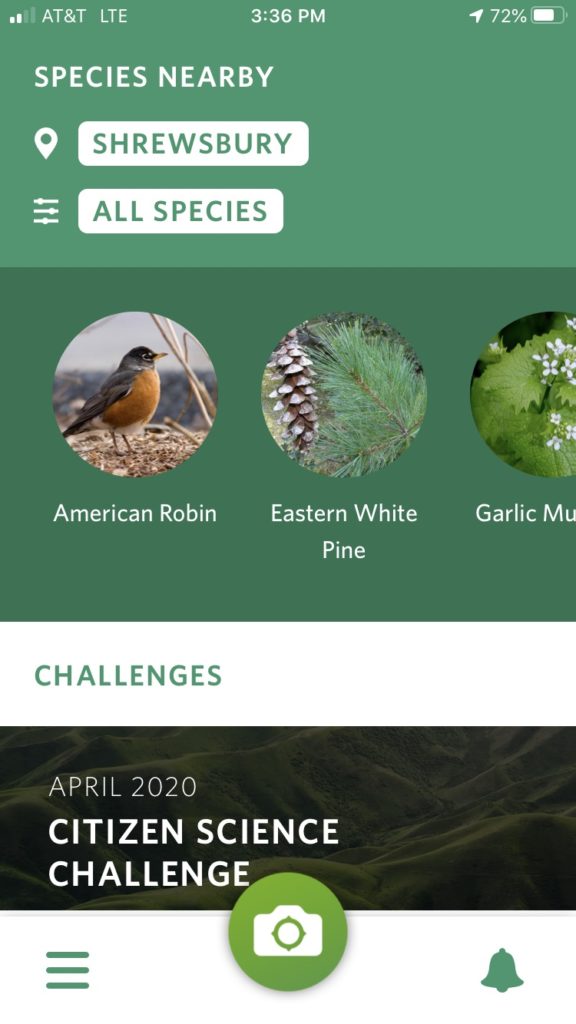

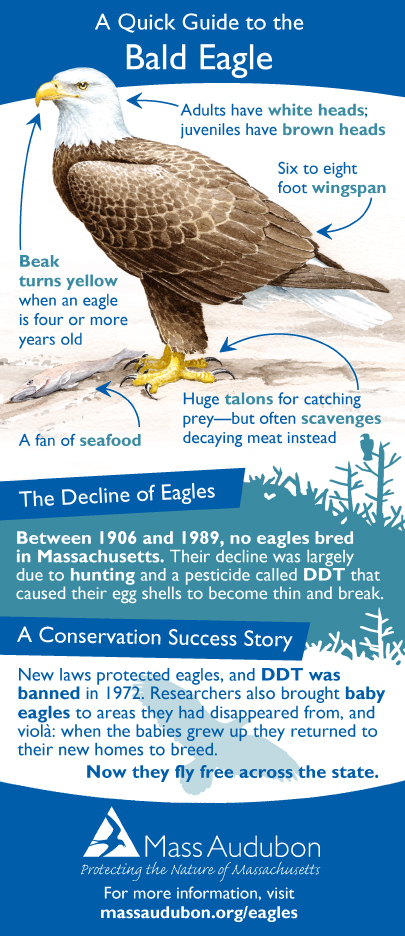

iNaturalist

This app is like social media for nature sightings. The platform is designed to connect people to a community of wildlife and plant enthusiasts. Create a (free) account and upload photo (or audio) observations of living things. iNaturalist will give you its best guess based on your location and identifications of similar-looking species. Other users can comment on your observations and suggest an ID, which helps the program better identify future observations. Plus, iNaturalist observations can be scientifically useful: iNaturalist’s database has been used to redraw species range maps, and even describe new species.

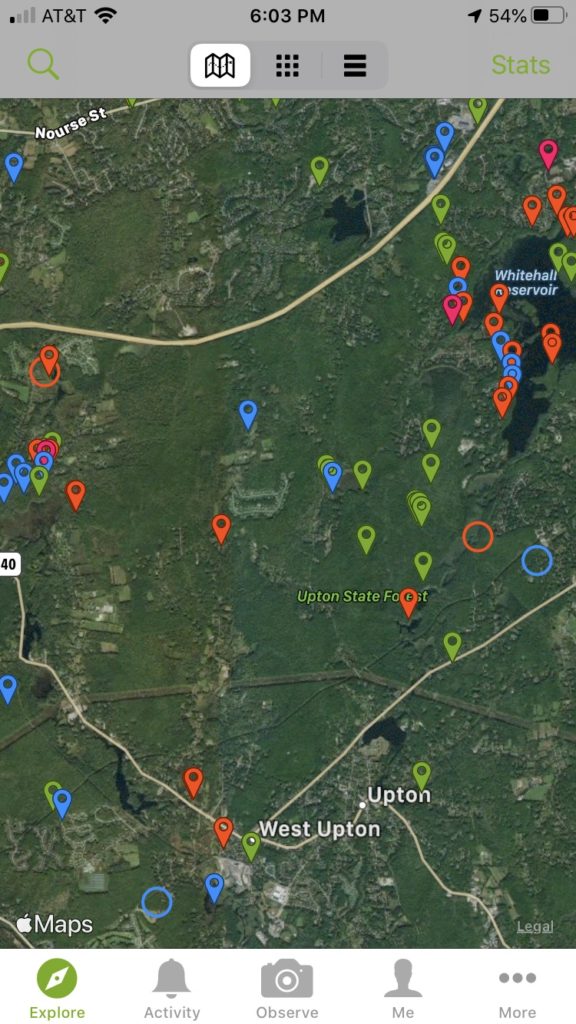

DIscover nearby observations under the “explore” tab. Each are color coded by taxonomy.

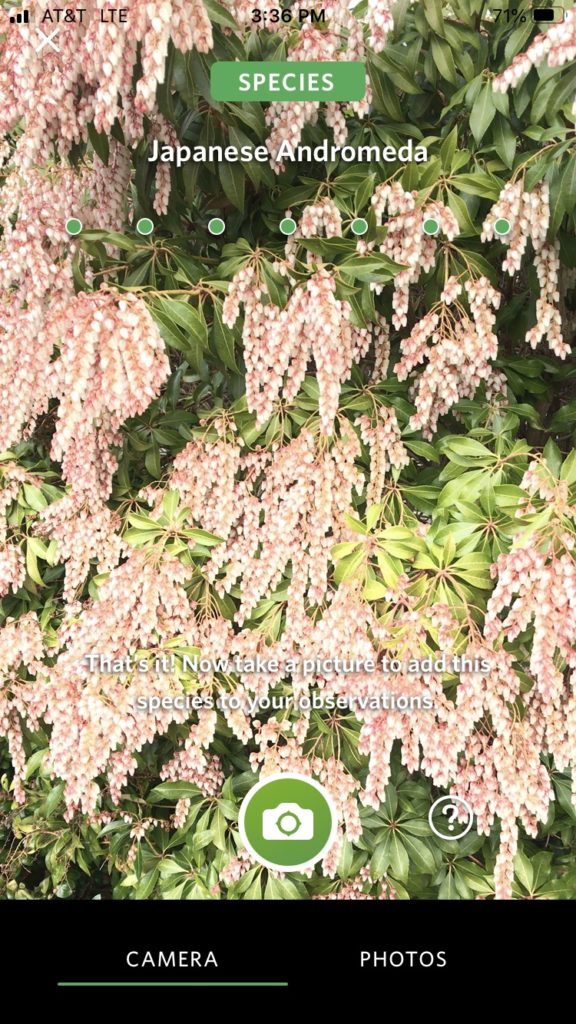

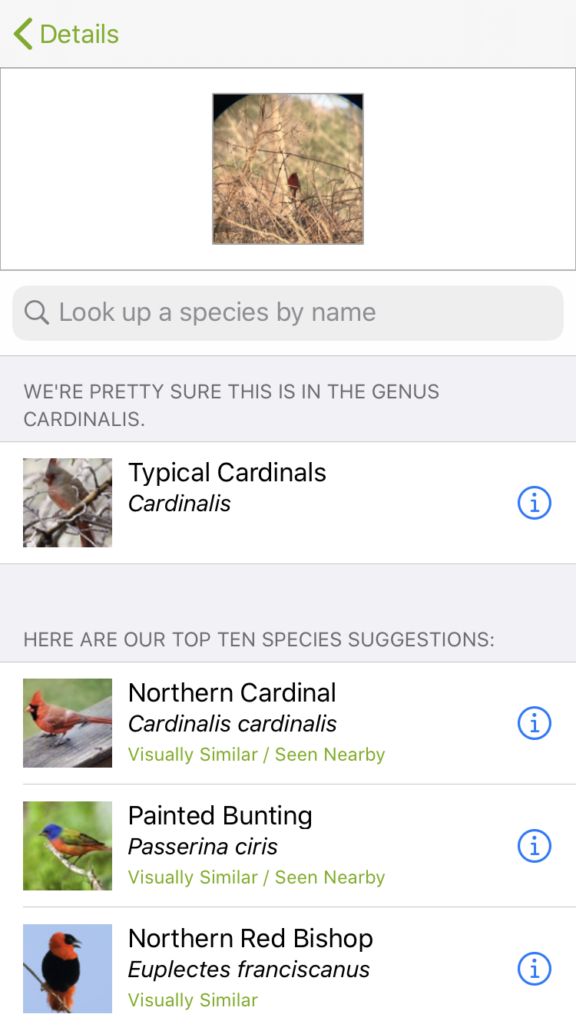

Seek

If you want to use iNaturalist’s identify tool without the rest of the app’s features, consider downloading Seek instead. This app has been described as “Shazam for nature” for its ability to ID a living thing by just pointing your camera.

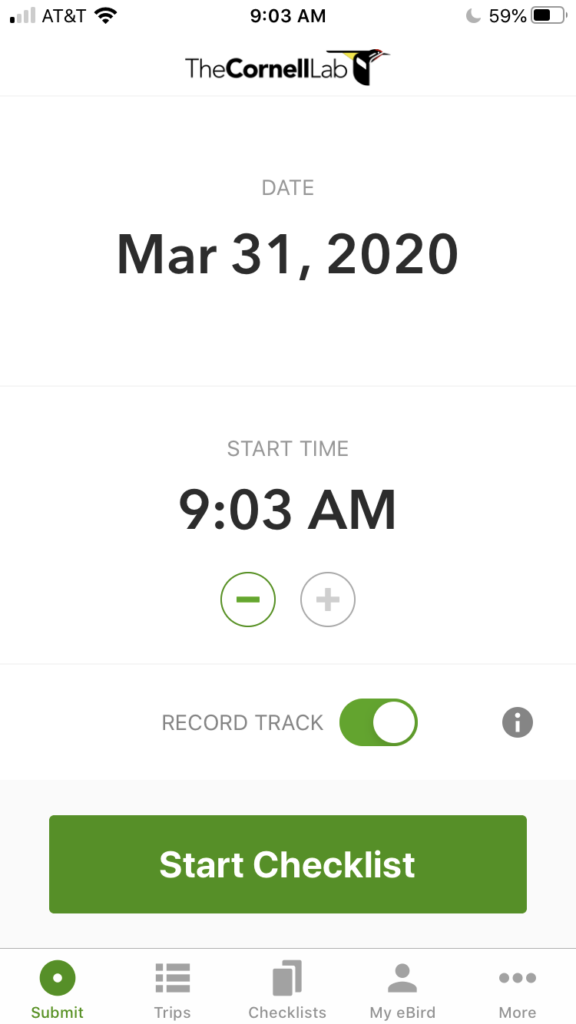

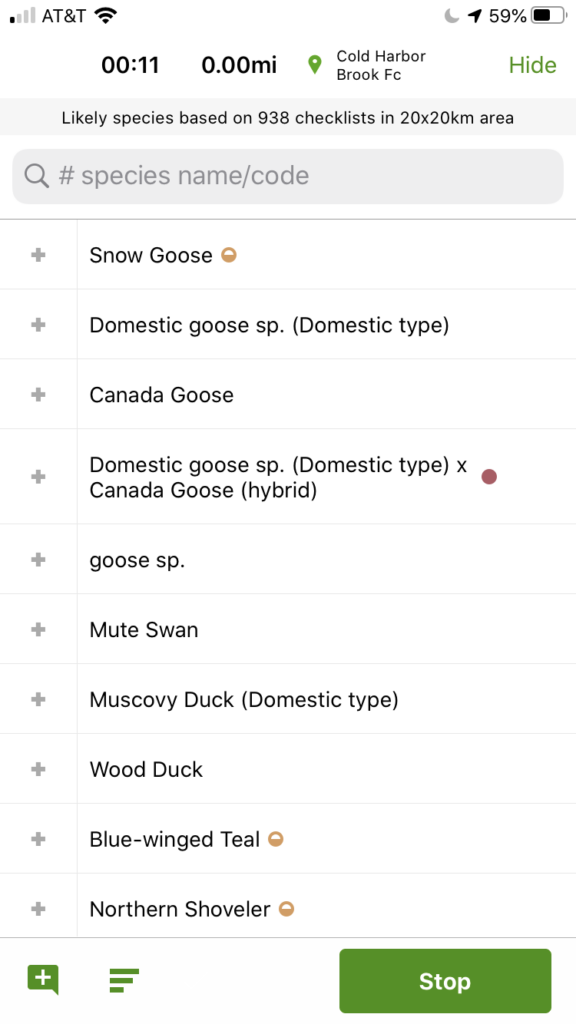

eBird

This app is for bird-lovers and life-listers. Create “checklists” of any birds you see in a fixed location or on a walk. eBird tracks your distance and time and shows you a list of possible species based on your location. A half-moon orange circle notes uncommon species for the area and a red circle notes rare species.

As with iNaturalist, eBird sightings become part of a database of millions of observations, helping scientists monitor large-scale patterns in bird populations.

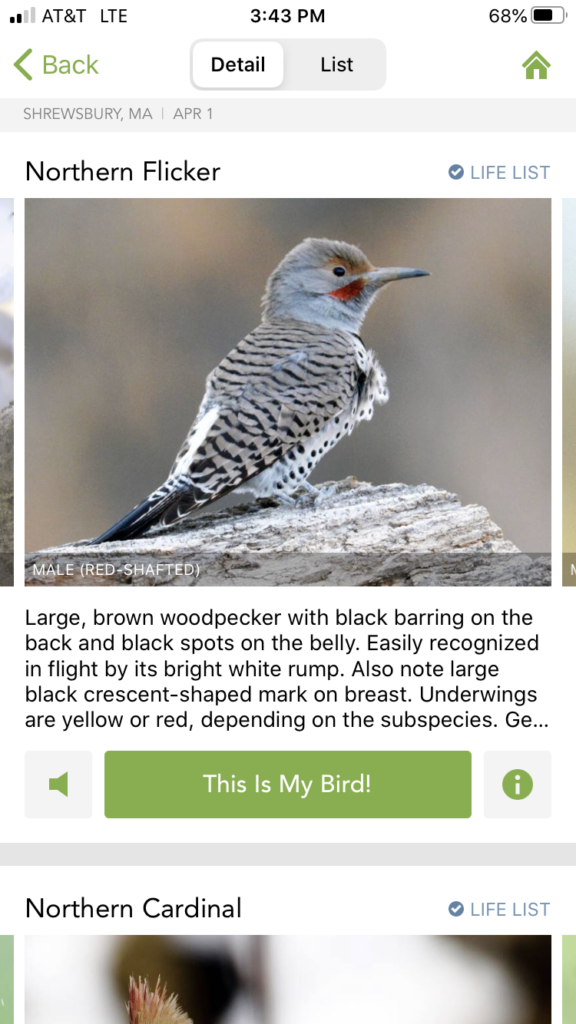

Merlin Bird ID

If you’re new to birding, consider downloading Merlin from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Browse a digital field guide of photos, bird sounds, and maps or answer five questions based on a bird you saw to have the app give you its best guess.

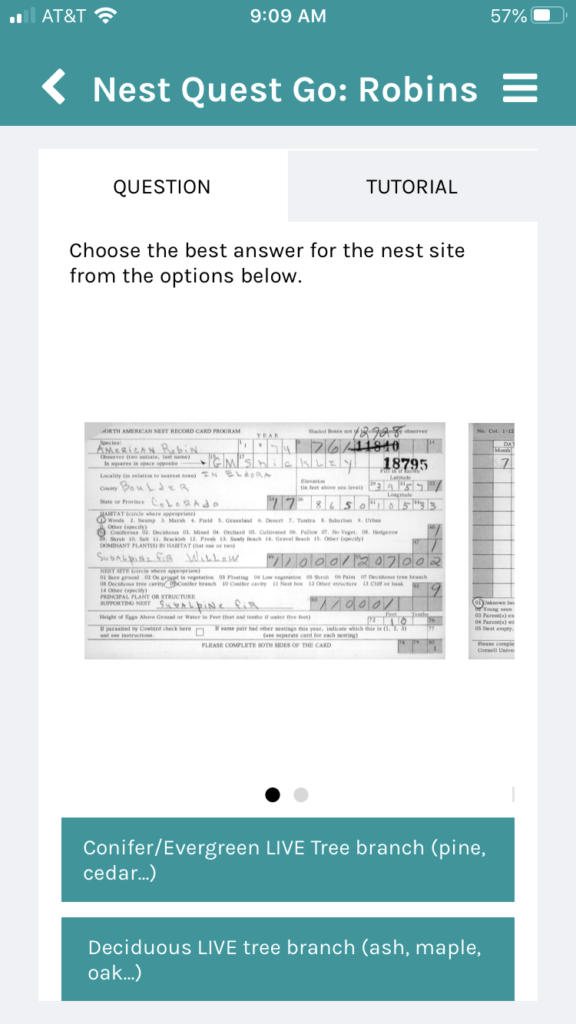

Zooniverse

Think of this app as digital volunteering. Instead of going out and monitoring nests, you can digitize historical nesting info (see below) that researchers at Cornell Lab of Ornithology will use for their database. Of course, this is only one of any citizen science projects on Zooniverse and topics range from nature to history and everything in between. The app will even track your progress, allowing you to see how much you’ve accomplished.

Let us know if you decide to use any of these, have used them before, or have other recommendations for nature-based websites and apps you love!