Conservation success stories rest on a bedrock of strong environmental laws. Many of Massachusetts’ most notable species recoveries, from the resurgence of Peregrine Falcons in cities to Bald Eagles populations’ dramatic turnaround, are grounded in the legal provisions of the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MESA).

MESA provides robust protections for over 400 local, rare, and declining species. With the chaos of 2020 disappearing in the rearview mirror, this is also a time to reflect on and celebrate positive achievements from past years. To mark the 30th anniversary of MESA, passed in December of 1990, take a moment to learn about the history of this sweeping and ever-relevant legislation.

Laying the Groundwork

Conservation laws in Massachusetts date back to 1818, when the state passed the first bill to protect songbirds from sport and food hunting, and by 1855 a broader act was instituted that protected all “nongame” birds. By the end of the Civil War in 1865, the genesis of today’s Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife came about with the establishment of a two-person commission “to investigate the obstructions to the passage of fish in the Connecticut and Merrimack Rivers.” By 1886 this grassroots political conservation effort became known as the Commission on Fisheries and Game.

As this incipient conservation machinery continued to evolve, by 1908 Edward Howe Forbush was appointed as the Commonwealth’s first State Ornithologist. After Mass Audubon’s Founding Mothers spearheaded the national Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918, the state was spurred to create the Massachusetts Department of Natural Resources. Embedded within this department, the Division of Fisheries and Game was essentially charged with conserving and managing the Commonwealth’s diversity of wildlife, plants, and habitats for the benefit of Massachusetts residents.

Conservation is a Team Effort

Through the years environmental legislation gradually grew stronger, and by 1973 the federal Endangered Species Act was passed. This landmark legislation soon saw The Nature Conservancy (TNC) develop a network of natural heritage programs across the country that would eventually oversee state level stewardship for all elements of biodiversity, including plants, animals, and natural communities. In 1978 Massachusetts became the fourth state to formally establish a Natural Heritage Program, which by 1983 had morphed into today’s Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program (NHESP). By 1990, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis signed the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act into law, designating species as Endangered, Threatened, or Special Concern, and providing legal protections for each status.

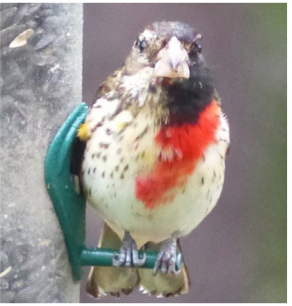

Since then, Mass Audubon has played a key role in partnering with the state to protect the Commonwealth’s most imperiled (“state-listed”) animals and plants through the efforts of the NHESP. Examples include such rare species as North Atlantic Right Whale, American Bittern, Red-bellied Cooter, Marbled Salamander, Northern Redbelly Dace, Early Hairstreak, Yellow Lady’s-slipper. Massachusetts publishes a complete list of state-listed species online. In other cases the NHESP’s Habitat Management Program focuses its conservation efforts on threatened habitats (e.g., vernal pools, pine barrens, sandplain grasslands, and calcareous fens).

As we enter 2021, the conservation efforts driven by the NHESP and MESA continue apace. For more information about the history of the Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program and the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act, check out the November issue of Massachusetts Wildlife magazine, or visit the Fish and Wildlife Service homepage for MESA’s 30th anniversary.