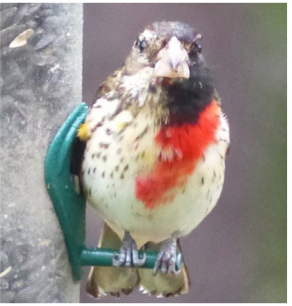

The Red Knot (Calidris canutus) is a shorebird, roughly the size of an American Robin, and similarly colored in spring, with rusty red underparts and a ruddy brownish back sprinkled with black and calico. This species’ legacy has been punctuated by eras of superabundance, intense market hunting persecution, habitat disruption, and most recently anthropogenic events that have nearly brought the Atlantic flyway population to its knees. Favored sandy beaches on the South Shore of Cape Cod Bay and outer Cape Cod in Massachusetts have for many decades hosted great numbers of “Robin Snipes” (so-called by early market gunners) during their autumn migration en route to the far reaches of southern South America for the winter. And it was on these same Bay State beaches that the Atlantic population of knots was mercilessly persecuted from July-October during much of the 19th and early 20th century.

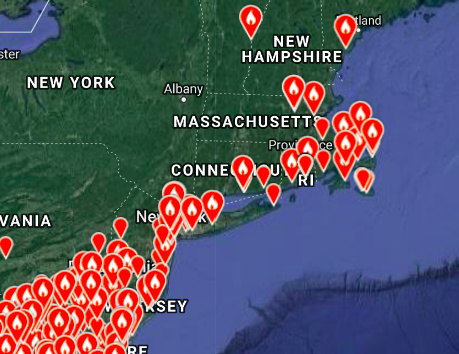

Fast forward to the last half of the 20th century when the ornithological community, initially in the Mid-Atlantic Coast region, began systematically registering measurable declines in the vast numbers of knots that once stopped on Massachusetts shores during autumn migration and on the shores of Delaware Bay in May. These early warnings presaged what was to become one of the most precipitous declines in modern shorebird history. The sad and well-documented chronicle of the near collapse of the eastern North American Red Knot population is one of the most dramatic sagas in modern-day bird conservation.

The pathos and intimate details of this ongoing conservation drama have recently been eloquently presented in Orion magazine by author and Audubon A awardee Deborah Cramer and artist Janet Essley. To explore the details of this fascinating story, follow this link >