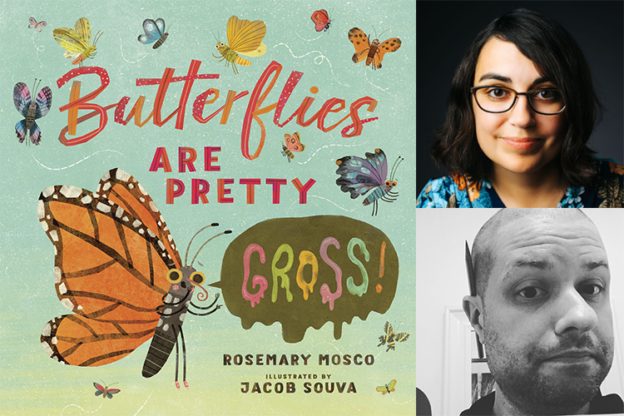

As part of Mass Audubon’s Earth Month festivities, you can celebrate what makes butterflies pretty and gross during the virtual book launch of the children’s book Butterflies Are Pretty…Gross with author Rosemary Mosco and illustrator Jacob Souva on Sunday, April 18 at 1 pm.

Listen to Rosemary read the story, watch Jacob give a drawing lesson, and learn from Mass Audubon Education Manager Martha Gach about how to attract butterflies to your neighborhood during this free, one-hour event.

About the Book

Butterflies are beautiful and quiet and gentle and sparkly . . . but that’s not the whole truth. Butterflies can be GROSS. And one butterfly in particular is here to let everyone know!

Talking directly to the reader, a monarch butterfly reveals how its kind is so much more than what we think. Did you know some butterflies enjoy feasting on dead animals, rotten fruit, tears and even poop? Some butterflies are loud, like the Cracker butterfly. Some are stinky — the smell scares predators away. Butterflies can be sneaky, like the ones who pretend to be ants to get free babysitting.

This hilarious and refreshing book with silly and sweet illustrations explores the science of butterflies and shows that these insects are not the stereotypically cutesy critters we often think they are — they are fascinating, disgusting, complicated and amazing creatures.