Gardeners are well-suited to help fight climate change, but sustainable gardening requires putting aside some traditional practices that work against nature.

Fortunately, there are plenty of ways to create a beautiful, natural, and functional landscapes that benefit the environment and our senses. Gardening sustainably also reduces the cost and labor required.

Purple Coneflower is a great climate-friendly addition to your garden.

Lawns are a Yawn

Over the country, our lawns add up to about 31 million acres, an area slightly larger than Mississippi. The cost of all that manicured grass is huge. According to the NRDC, Americans consume 3 trillion gallons just to water our residential lawns (about half the volume of Lake Champlain), 200 million gallons of gas to power our lawn equipment, and 70 million pounds of pesticides every year. On top of the ecological burden, lawns deprive birds and other wildlife of useful habitat and food, creating areas with little environmental value.

Instead of keeping large, open lawns, turn your yard into miniature sanctuaries for birds and pollinators. For species feeling other stresses from climate change or loss of habitat, having a backyard stop to rest and refuel can support them when they need it most.

Plant Native Species

Choose native plants whenever possible. They help grow far more insects and provide better resources for birds and pollinators. Since native plants are adapted to a New England climate, they’ll also require less protection and effort to maintain. In Massachusetts, butterfly bushes and purple coneflowers are a couple excellent choices among many. Find some great native options.

Avoid Nitrogen Fertilizer

Producing and transporting fertilizers that include urea and ammonium nitrate, which are common in inexpensive home lawn care fertilizers, requires a lot of energy. Four to six pounds of carbon are emitted for every pound produced, so even modest use increases a garden’s carbon footprint. Overusing fertilizers (a common mistake) releases nitrous oxide, which has 300 hundred times the warming potential of carbon dioxide and makes a garden’s carbon footprint excessive.

With stronger, more frequent storms, we’re also seeing more nitrogen-loaded runoff in waterways. The buildup contributes to harmful algae blooms and toxic dead zones. Avoiding the use of such fertilizers helps offset the impact of stronger storms due to climate change.

Replace nitrogen fertilizers with manure or locally-produced compost sparingly and strategically.

Plant Trees

Trees or other woody plants help remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, so plant as much of your property with trees and rigid shrubs as possible.

Placing trees, shrubs, and vines to block winter winds and create summer shade can reduce the amount of energy required to heat and cool your home. Red Oaks, Red Maples, and Dogwoods are good native choices that should remain resilient to changing climate conditions over the next few decades.

Save the Rain

Gardens filled with native plants will generally thrive with normal amounts of rainwater, saving the time, energy, and water of irrigation. When you need more than what the weather is providing, or at different times, collect and store water with rain barrels, or sculpt your land to drain to areas where you want the water to go slowly and effectively, using what you receive as efficiently as possible.

Grow Your Own Food

Growing fruits and vegetables at home reduces your carbon footprint. It’s the ideal way to “eat local.” It eliminates the fuel needed to transport, store, and process food elsewhere. Grow plants from seed and make your food garden as diverse as possible, while mixing perennials with annuals. Berries are a great perennial option, as is rhubarb. Asparagus, grown commercially actually has a high carbon footprint, so growing your own can be a big help. Kale and garlic are good to grow as annuals.

Trade in Gas-powered Equipment

Reduce usage of gas-powered equipment like mowers, weed whackers, and leaf blowers as much as possible. Your neighbors will love you for it and you’ll be keeping carbon out of the air. When you can, use manual equipment: rakes, reel mowers, and shears. When necessary, use electrical equipment.

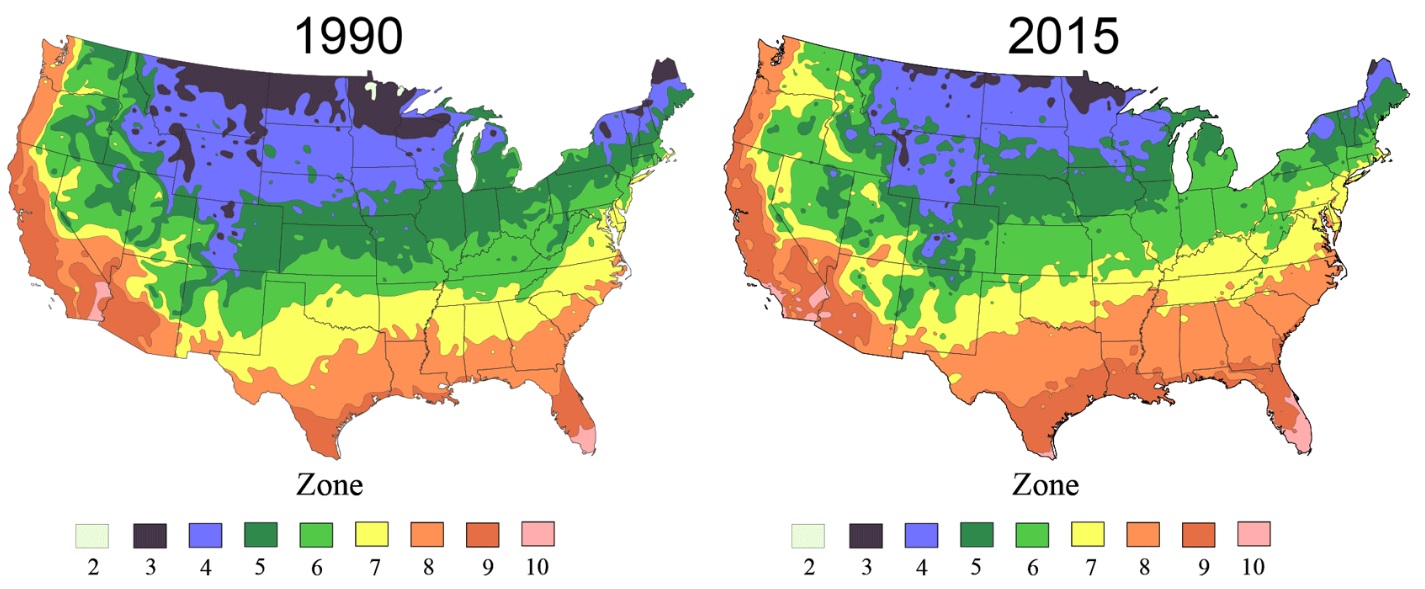

Plant Hardiness Zones, 1990 and 2015. Images from USDA and Arbor Day Foundation.

Plant Hardiness Zones, 1990 and 2015. Images from USDA and Arbor Day Foundation.