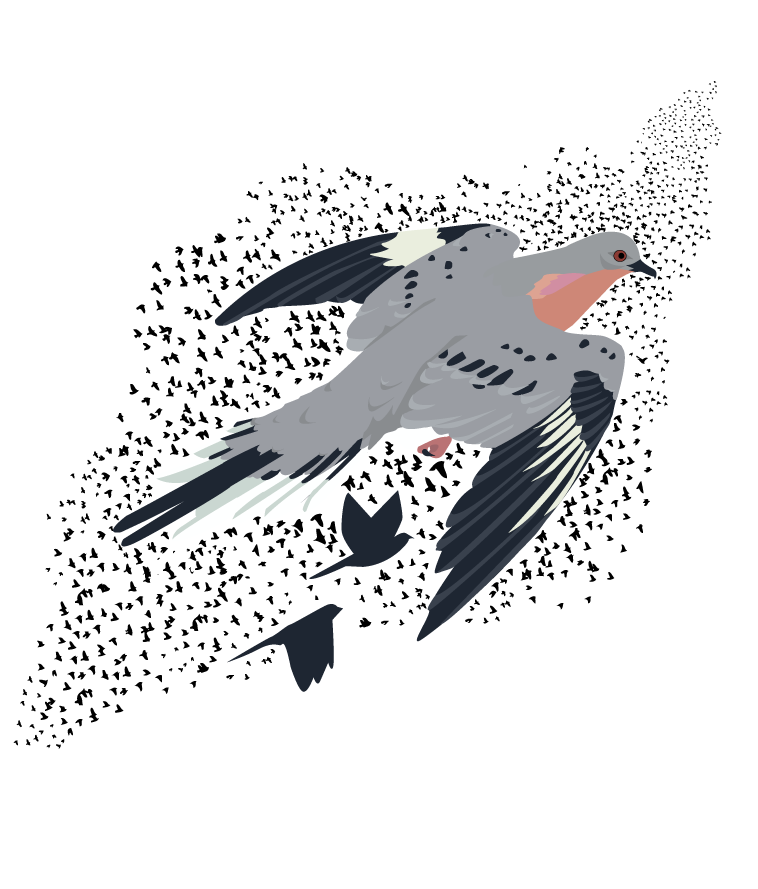

John J Audubon’s Passenger Pigeon

September 1, 2014 marks the 100th anniversary of the passing of Martha, the last known passenger pigeon. Martha died after a long captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo, having outlived all of her cage mates.

With her loss, and the extinction of an entire species, a heavy burden was passed to the then new field of wildlife conservation: learning to manage and advocate for the conservation of seemingly endless resources in a time of rapid population growth, massive technological development, and a dearth of laws protecting our natural resources.

About Passenger Pigeons

Over much of their extensive US range, passenger pigeons were “birds of passage”—nomads that traveled the nation in enormous flocks, looking for places where mast foods such as acorns and beechnuts were abundant. Their population was estimated to have numbered in the billions of birds as late as the second half of the 19th century. Other estimates put the total number of passenger pigeons as roughly equal to the total number of birds we have wintering in North America today.

Passenger pigeons were the most numerous bird species in North America, maybe even in the world. By rights, they should have been the national bird. Rich blue, grey, and cinnamon, fairly large, fast flying, and likely with a cooing call, the flocks were said to be deafening when they passed over.

The gregarious birds set up massive colonies, with hundreds of birds nesting in each tree. They were exceptionally social, flocking during breeding, migration, and winter, searching for food and suitable nesting areas together, nest building across a colony with remarkable synchrony, and raising their single young together. They were icons of the vast forests of pre-colonial North America, but their reign couldn’t survive the industrial age.

Their Fall

Even with such a dense population, the passenger pigeon fell victim to unrestricted hunting by humans. There are reports of single hunters killing 3 million birds in their careers, reports of one colony having 50,000 birds killed each day for five months.

Even with such a dense population, the passenger pigeon fell victim to unrestricted hunting by humans. There are reports of single hunters killing 3 million birds in their careers, reports of one colony having 50,000 birds killed each day for five months.

They were used for human food, for feather beds and pillows, as live “targets” for trap shooting, and as food for pigs. They were taken with all manner of tools, nooses on poles, by setting fire to their nesting trees, with nets, with sulpher smoke, and by luring them in with “stool pigeons” – live decoys used to attract wild birds.

Some were dressed, salted and shipped to market, some were brought in live and fattened to be more commercially valuable. They were so plump that the native people of North America stored their fat like butter. The take was so high that eventually the price dropped and they were worth less than the value of the barrels and ice needed to store them – so they started to ship them live.

Too Little, Too Late

Laws were passed in many places to protect the passenger pigeons’ massive nestings “cities”, where tens or hundreds of millions of birds would settle in trees across several square miles, but many of these laws were passed too late and lack of enforcement made even the more timely laws ineffective.

The pigeons could sustain some of this onslaught, but the advent to good firearms, refrigerated train cars, and the telegraph (to let all the other hunters know where the big colonies were) was too much. The last wild Passenger Pigeon was killed by a boy with a gun in 1900.

Cautionary Tale

While we know more now than our predecessors, we still see history repeat. By taking too many horseshoe crabs (another seemingly endless and until recently a nearly unprotected resource) for bait we have forced Red Knot to the brink.

Luckily our successes outweigh our foibles here in Massachusetts. But Martha stands as a reminder of the sort of disaster that forged Mass Audubon, and also as a reminder that the unimaginable does not make something impossible.

— Joan Walsh, Director of Bird Conservation & Matt Kamm, Bird Conservation Assistant