Some animal species look very similar to each other. Here are some tips for distinguishing a few of the trickier lookalikes you’ll find at our wildlife sanctuaries.

Monarch vs Viceroy

Everybody’s on the lookout for monarchs lately, but don’t be fooled by the viceroy. This black and orange butterfly looks so much like a monarch that it’s hard to believe they’re not closely related.

Scientists have long known that monarchs are poisonous to predators. They used to believe that viceroy butterflies copied the monarchs’ patterns to trick predators into leaving them alone as well. However, we now know that birds find viceroys distasteful, too. In fact, these butterflies share a similar appearance so that if a predator has a bad experience eating one, it’ll leave both species alone.

There are several subtle differences between the two species, but the simplest way to tell the difference is to look for the extra black band on the hind wings of the viceroy.

Monarch Viceroy

Green Frog vs Bullfrog

These greenish-brown frogs live in permanent wetlands like ponds and marshes. Green frogs typically grow up to about 4 inches, whereas bullfrogs can grow up to about 6 inches. But how do you know if you’ve found a green frog or a young bullfrog?

Green frogs have two ridges—one on either side of the body—that start behind the eye and run down the back. Bullfrogs have much shorter ridges; these also start behind the eye, but stop after curving around the circular hearing organ (called a tympanum).

The two species also have very different calls. The green frog makes a sound like a banjo string being plucked—“gunk.” The bullfrog makes a deep sound like “gr-rum.”

Green Frog American Bullfrog

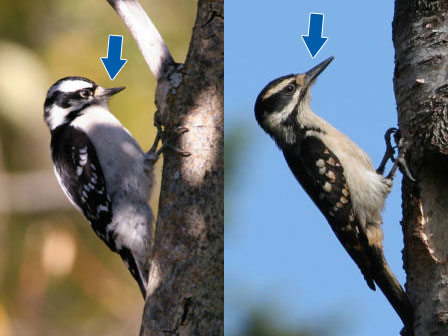

Downy Woodpecker vs Hairy Woodpecker

These two woodpeckers share similar black and white patterns, and in both species, males have a dot of red on the head. To tell these two apart, look at the beak.

The downy’s beak is very small—about a third the length of the rest of the head. The hairy’s beak is as long as the rest of the head. Also, the white outer tail feathers on a hairy woodpecker are typically white, whereas on a downy, they’re patterned with black and white.

Also, you’re more likely to see downy woodpeckers in urban areas; hairy woodpeckers prefer spaces with less human activity.

Downy Woodpecker Hairy Woodpecker

Tell us about the similar-looking species that you find most challenging, and we’ll keep them in mind for future articles about lookalikes.

Woodpecker photos via USFWS

You may have seen the story in the

You may have seen the story in the