It’s a seasonal rite of passage in New England. By mid-February, maple trees across the region are affixed with silver buckets ready and waiting to catch the sweet sap as it drips through the tap.

It’s a seasonal rite of passage in New England. By mid-February, maple trees across the region are affixed with silver buckets ready and waiting to catch the sweet sap as it drips through the tap.

Looking to learn more about maple sugaring, and how to get involved? Keep reading.

The Sappy Story

There are many legends about how maple sugar was first discovered. One Iroquois legend tells how Chief Woksis had thrown his tomahawk into a maple tree one winter evening. After he removed it, the weather turned sunny and warm. Sap began to flow from the cut in the tree.

Most likely the Native Americans discovered the sweetness of the maple tree by eating “sapsicles,” the icicles of frozen maple sap that form from the end of a broken twig.

The most common early method of collecting sweet sap was to make V-shaped slashes in the tree trunk, and collect the sap in a wooden vessel. With the advent of drills, both Native Americans and European settlers started drilling holes in the trees and inserting spiles made of a softwood twig such as sumac or elderberry to allow the sap to run out. This was much less harmful to the tree and more efficient for collection.

These days, at Mass Audubon, we use metal spiles and buckets as well as wood fired evaporators. Larger scale producers use plastic spiles and tubing that runs from tree to tree and then into big collecting tanks. Many producers also now use freeze-thaw separation systems or reverse osmosis to remove some of the water before they boil the sap in large, gas-fired evaporators.

Sweet Tree

While all maples have sweet sap, sugar maples, Acer saccharum, produce the best sap for sugaring. The sap of the sugar maple has higher concentrations of sugar than other members of the maple family, and produces better flavored, lighter syrup.

The sugar maple is a large, long lived, slow growing, hardwood tree. A tappable tree should be at least 12 inches in diameter, which takes about 40 years for a sugar maple.

Watching the Weather

Sugar maples will run sap only when the weather conditions are right. The normal tapping time in Massachusetts is mid-February to mid-March. Sap will run when nights are cold, 25° F or below, and days are warm, 40° F or above.

The depth of the snow on the ground during the season is also a factor in sap season. If there is a deep layer of snow on top of the frozen ground during maple season, the snow will help extend the season by keeping the ground frozen longer. Frozen ground helps to slow the development of the tree’s leaf buds, and delay the “buddiness” of the sap.

From Sap to Syrup

Once the sap is collected, it heads to the evaporator, where it boils down, creating the steamy plume that makes everything smell so sweet. It takes 4 to 6 hours of continuous boiling before the sap reduces enough to become delicious maple syrup. It gets strained and bottled and then it’s ready to eat!

Join the Fun

Explore the sweet side of nature and take part in the New England tradition! In February and March you can experience the art and fun of maple sugaring at Mass Audubon wildlife sanctuaries, with tours, festivals, programs, and pancake breakfasts.

Looking to tap on your own? Pick up supplies and a manual at the Audubon Shop in Lincoln.

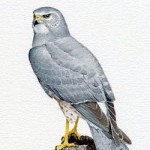

Northern Harriers

Northern Harriers