Flyways

I lived a good life

and was reborn a sparrow.

Towhee-like

I scratched meals

on the ground

with both feet

but mostly I flew,

threading a needle

through dense thickets,

wheeling in legions

above power lines.

My breast was streaked

white and brown,

my bones

an invention of light.

Crossing low alone

in clearings I felt

I soared:

then a pane of glass

in what had seemed

a clearing.

So the reality

I meant only to pass through

contracted

to an instant

and killed me.

God had mercy

and remade me as

a blackbird.

In the marsh

it was sweet:

I built my nest,

wove a wet cup

about the cattails.

The walls

were bur-reed and rush

the bed inside

grass dry and soft. And oh

I loved the brood

with eyes tight shut.

For my baby

seed of the field,

damselflies

for my baby. But you

do not grow fat–

I paired again,

my mate distinguished

by song:

a choking,

scraping noise

made with much

apparent effort.

Expiring

without legacy

I begged to still

be winged An ivory

gull A plover

A thrush

And mercy

was endless

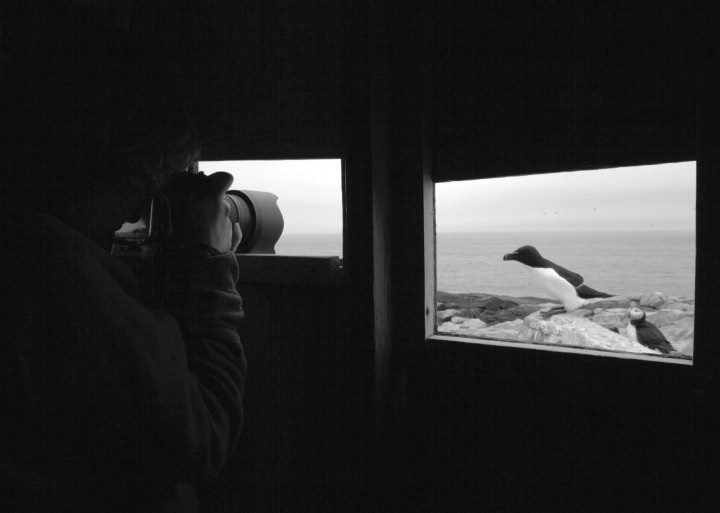

As a guillemot

I returned

starving slick

in my own color

as murre in

Alaska I starved

as one penguin

of 40,000

Then God blessed me

at last I was a sea bird

in Australia I floated

in the water

I ate everything

the world gave me

And then I was full

O Heaven Then

I realized my need

could not be met

There is an emotional toll, for birders and nature-lovers, in reading so frequently about the scale of bird declines. Summaries of recent scientific papers, updates on population trends, and calls to action can fail to address the sadness and loss readers feel at more bad news. These reactions are just as real as the ecological damage that provokes them, and scholars increasingly recognize them as “ecological grief.” For all the successes of conservation movements, the declines of many species continues unabated, and each feels like a defeat.

Kolding approaches these defeats from a bird’s perspective— in fact, from the perspective of several birds. She treats an indefinite number of birds killed by human activity as reincarnations of one consciousness, condensing a wide and complex range of conservation threats into a linear, tragic story. In so doing, Kolding’s poem resists the treatment of bird deaths as statistics.

While this poem takes ample (and poetically necessary) liberties in ascribing feelings to birds, its poignance is grounded by accurate natural history details and descriptions of real threats. The last passage (“I ate everything the world gave me/ And then I was full… Then I realized/ my need could not be met”) both describes a complex emotion— the dread of living in an unsurvivable world, or of asking in vain for what you need— while also reflecting the reality of how some seabirds die. Plastic pollution kills seabirds because they eat indigestible plastic debris, which accumulates inside them until they starve with a full stomach. (Plastic in the ocean smells like food to seabirds because it grows the same algae as decomposing fish).

In each of Kolding’s vignettes, she frames a scientist’s perspective on birds with a poet’s sensitivity and imagination. The result is a both refreshing and profoundly sad approach to thinking about conservation losses.