American Kestrels, Barn Swallows, and Cliff Swallows are all declining in Massachusetts, like many other open-country birds. The Bird Conservation team is initiating two exciting studies on these species during this spring and summer, and data from the community will be integral to both studies’ success!

Have you seen these birds nesting?

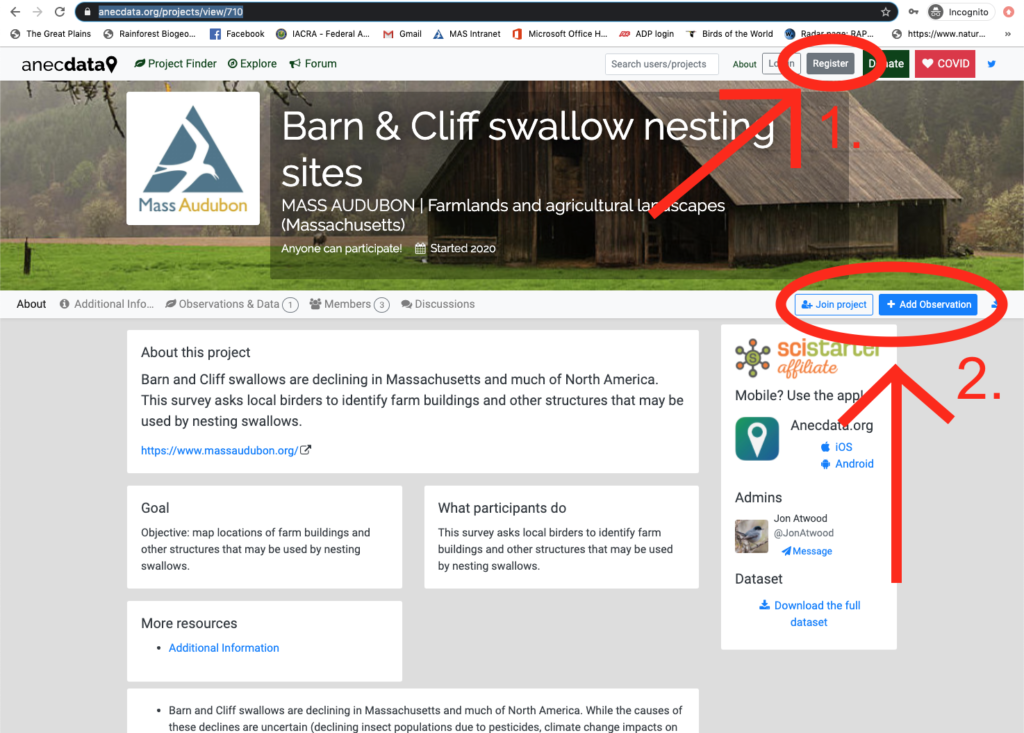

If you have any information on these species’ current (2020) nest sites, or are willing to look for them, please submit data via our swallow project and kestrel project webpages on Anecdata (a citizen science website).

You’ll need to set up an Anecdata account first. Click on “register” to first create an account, and click on “join project” once you’ve signed up with Anecdata.

Both projects are fairly simple for users: simply click on “add an observation” and report the coordinates of nesting American Kestrels, Barn Swallows, and Cliff Swallows. In the case of both swallow species’, it’s also useful to know if you observe structures that do NOT host a colony but which you think potentially could (e.g., old barns or small wooden bridges near open grassland and freshwater). Note that this study is focused on nesting sites, not places where birds are observed foraging or flying around.

What we hope to accomplish with your help

The purpose of the swallow project is straightforward: we want to identify sites where Barn and Cliff Swallows are nesting that may not yet be known to biologists.

Mass Audubon’s work on the kestrel project on the other hand, will be a little more involved. After compiling a list of remaining nest sites, the Bird Conservation Department will team up with state biologists in 2021 to fit kestrels with radio tags. These tags will track their movements around the region after nesting, and eventually to their wintering grounds.

Kestrels breed widely throughout Massachusetts, but there are many Breeding Bird Atlas blocks that showed declines between Atlas 1 (1974-1979) and Atlas 2 (2007-2011). Interestingly, there are both urban-nesting and farmland-nesting American Kestrels, and the two populations may be showing different population trajectories. Studying the life histories of these birds, including tracking their movements away from nest sites, could hold clues as to why so much apparently good kestrel habitat goes unoccupied in the state.

As always, all nest data is kept strictly within the community of biologists working to conserve these species.

More Tips For Searching

- Both projects run from May 20 – August 20, to reduce potential confusion between nesting birds and migrants.

- The focus is on nest sites and not on places where birds are seen flying around.

- If you need a refresher on identifying Barn and Cliff Swallows in the field, check out our ID tips for these similar-looking birds.

- Please participate only if you can do so in your own local communities.

- It’s likely that some sites will be on private property where direct observer access is impossible. Please don’t trespass! Even if you’re only able to observe from a road edge and can’t collect, it’s helpful to know that you saw swallows or kestrels entering or leaving a particular cavity or structure.

All three of these species were once common sightings in rural parts of Massachusetts, and they’re all a joy to observe and spend time near. Thank you for helping Mass Audubon protect them, and happy birding!