In honor of Women’s History Month, we’d like to share the story of the two women who not only founded Mass Audubon but were responsible for instigating the modern environmental movement.

Excerpted from Sanctuary magazine, by John H. Mitchell

One of the seminal events in the history of environmental activism in this country took place in a parlor in Boston’s Back Bay in 1896. On a January afternoon that year, one of the scions of Boston society, Mrs. Harriet Lawrence Hemenway, happened to read an article that described in graphic detail the aftereffects of a plume hunter’s rampage—dead, skinned birds everywhere on the ground, clouds of flies, stench, starving young still alive in their nests—that sort of thing. The slaughter was in the service of high fashion, which dictated in those times that ladies’ hats be ornamented with feathers and plumes, the more the better.

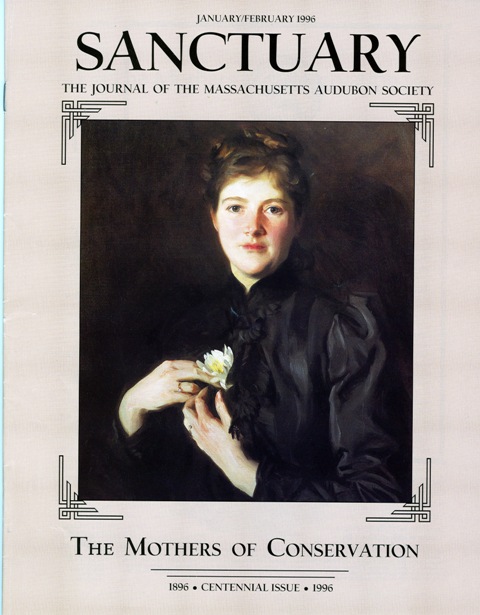

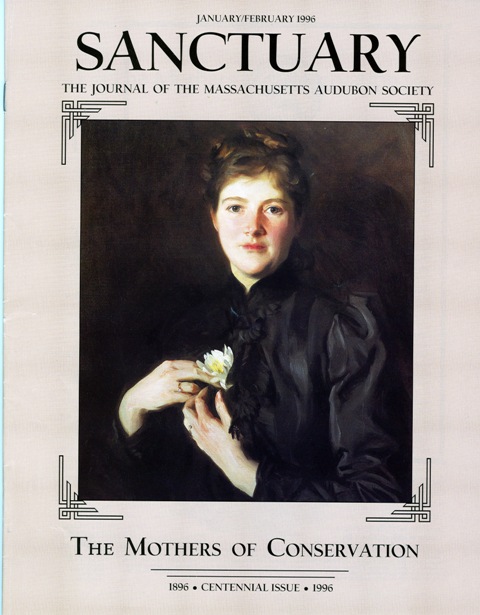

Young Harriet Hemenway

Harriet Hemenway was properly disturbed by the account, and inasmuch as she was a Boston Brahmin and not just any lady of social rank, she determined to do something about it. She carried the article across Clarendon Street to the house of another social luminary, her cousin Minna B. Hall. There, over tea, they began to plot a strategy to put a halt to the cruel slaughter of birds for their feathers. Never mind that the plume trade was a multinational affair involving millions of dollars and some of the captains of nineteenth-century finance; the two women meant to put an end to the nasty business.

…[Harriet] and Minna Hall took down from a shelf The Boston Blue Book, wherein lay inscribed the names and addresses of the members of Boston society. Hemenway and Hall went through the list and ticked of the names of those ladies who were likely to wear feathers on their hats. Having done that, they planned a series of tea parties. Women in feathered hats were invited, and, when they came, over petits fours and lapsang souchong, they were encouraged, petitioned, and otherwise induced to forswear forever the wearing of plumes.

After innumerable teas and bouts of friendly persuasion, Harriet and Minna established a group of some 900 women who vowed “to work to discourage the buying or wearing of feathers and to otherwise further the protection of native birds.” Hunters, milliners, and certain members of Congress may have found the little bird club preposterous…

After innumerable teas and bouts of friendly persuasion, Harriet and Minna established a group of some 900 women who vowed “to work to discourage the buying or wearing of feathers and to otherwise further the protection of native birds.” Hunters, milliners, and certain members of Congress may have found the little bird club preposterous…

But the opponents of any regulation on the trade underestimated their opposition. The Boston club was made up of women from the families of the Adamses and the Abbots, the Saltonstalls and the Cabots, the Lowells, the Lawrences, the Hemenways, and the Wigglesworths. These were the same families that brought down the British empire in America. This was the same group that forced Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, and it was these families that were about to create the American tradition of environmental activism. Within a matter of decades, the little bird club had spawned what would be the most influential conservation movement in America up to that time.…

Notorious, independent Boston women notwithstanding, these were not the freest of times for society women, and Hemenway and Hall were wise enough to know that if their group were to have any credibility it would need the support of men, and most importantly, would need a man as its president, even if he would be a mere figurehead. The women organized a meeting with the Boston scientific establishment, outlined their program, and got men to agree to join the group, which would be called, they decided, the Massachusetts Audubon Society, in honor of the great bird painter John James Audubon.

Download a pdf of the entire story, which was published in the January/February 1996 issue of Sanctuary magazine.