We are delighted to introduce a new series in our Taking Flight blog, Art Views, a fascinating collection of personal perspectives. Artists, collectors, MABA staff and other art enthusiasts have generously agreed to write about bird art that is meaningful to them. Posts may be about how an artist approaches their work, profiles of artworks in MABA’s collection, or whatever catches our guest bloggers’ fancy. Keep reading, share your comments, and enjoy!

~ Amy Montague, Museum Director of the Museum of American Bird Art

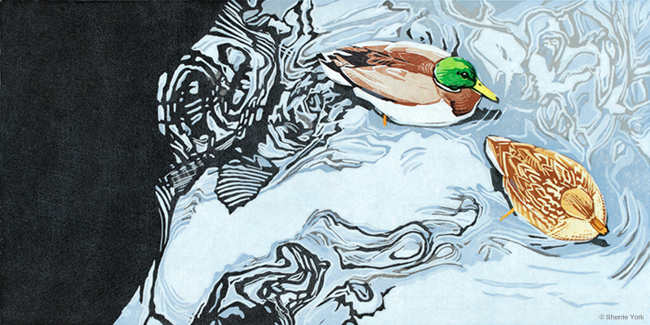

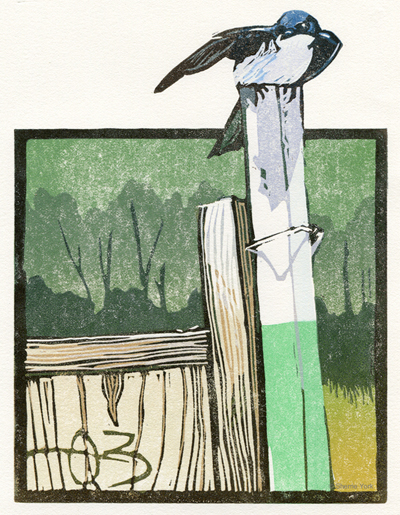

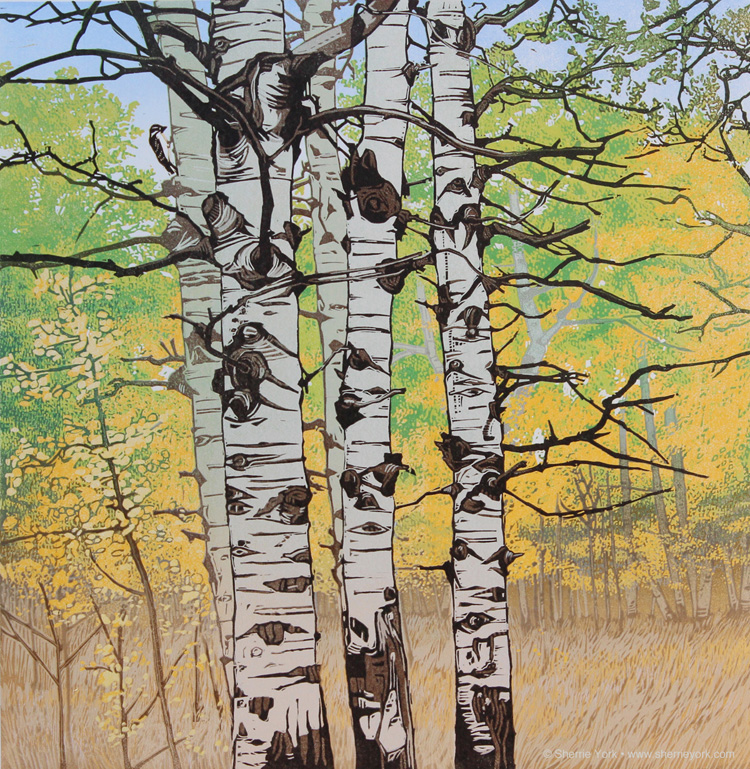

Trunk Show by Sherrie York

I’ve always been a fan of the “shoulder” seasons. Each day of spring and autumn is dynamic and exciting; migratory birds come and go, flowers and trees blossom and seed, and the balance of day and night waxes and wanes.

Although I now live in Maine, I grew up and spent most transitional seasons in Colorado, where spring is slow to arrive and high country autumns are intense and fleeting. In September, acres-wide stands of aspen trees quake with color as they turn from bright green to brilliant gold (and sometimes red!), but their show can be over with one strong wind or an early snow.

One of my favorite haunts during Colorado autumns was an area called, appropriately, Aspen Ridge. Every time I explored the ridge I was drawn to the cluster of large-trunked trees depicted in my linocut, “Trunk Show.” In fact, these same trees have been the subject of several sketches, paintings, and linocuts over the years.

Of course I’m not the only one who liked to visit this grove. Aspen stands are important in the west because they support a greater diversity of bird species than the surrounding coniferous forests. Woodpeckers, nuthatches, chickadees, warblers, flycatchers… they all rely on aspen.

When I moved to Maine just over two years ago I looked forward to discovering the rhythms and colors of seasons in the northern hardwood forest. I was delighted to find a few familiar aspen trees in between the oak, birch, and spruce behind my house, but even more comforted by the presence of some of the same bird species common to aspen groves. The woodpeckers and chickadees in particular are constant companions.

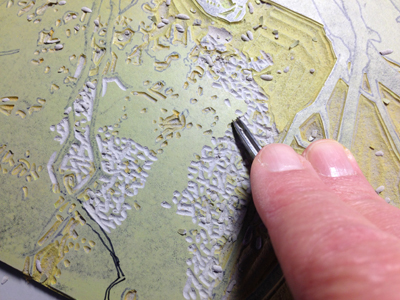

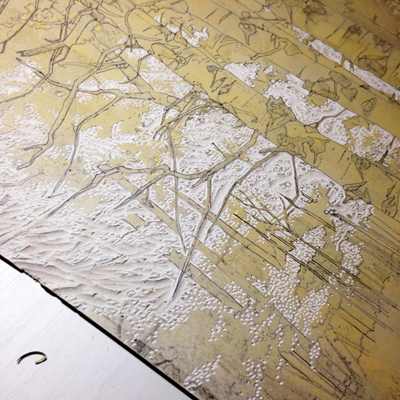

As a printmaker my first quest is always for a strong composition and graphic elements. These must be decided upon and resolved before block carving or ink rolling can begin, because carved areas can’t be erased or painted over. The vertical white trunks and dark “eyes” of the aspen tree are just such elements, and the shapes and patterns of the leaves offer a great opportunity to play with color and texture.

In the world of fashion, a trunk show provides an opportunity for designers and wearers to meet in a more personal and intimate way. In the larger world of nature, time spent with tree trunks allows to meet our neighbors and discover all the ways in which we are connected.

My linocuts are most often developed using a process called reduction printing. All of the colors in an image are printed from a single block of linoleum in successive stages of carving and printing. “Trunk Show” required 14 individual stages of carving and printing. It’s too much to share in a single post, but if you’d like to see how the entire piece developed, I documented all the stages on my blog, Brush and Baren. The series begins here: https://brushandbaren.blogspot.com/2016/09/linocut-in-progress-autumnal-endeavor.html