This is a blog post by Sarah Howdy, an amazing educator and Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice (DEIJ) specialist at the Museum of American Bird Art and Mass Audubon’s Metro South Hub.

Mass Audubon understands the existing and increasing need to dismantle both the symptoms and causes that lead to Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) feeling unwelcomed in outdoor spaces. We understand the healing power of nature, and are working to create healing spaces throughout the land that we occupy.

The lack of representation when it comes to racial diversity in the outdoors, in social media depictions of nature, in our workplaces and beyond leads to a lack of understanding and empathy for people from all walks of life. So often missing from popular narratives and imagery of the outdoors, BIPOC are environmentalists and nature lovers deserving of greater representation and active inclusion.

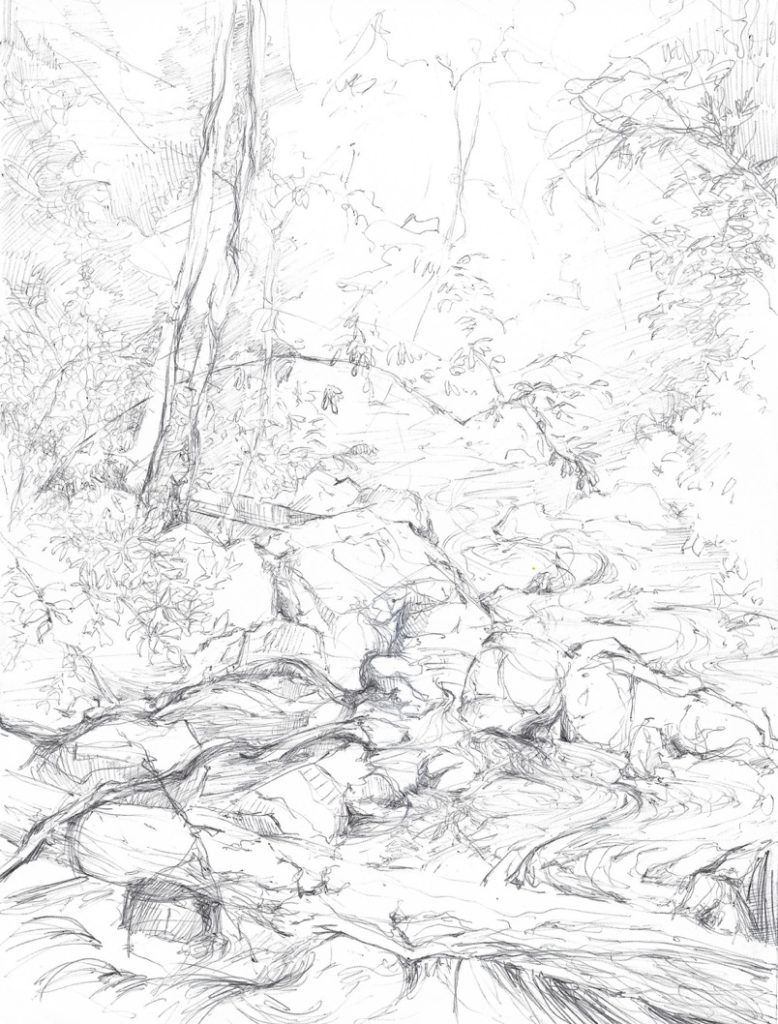

Recently, our first in a series of BIPOC hikes occurred at the wildlife sanctuary at the Museum of American Bird Art.

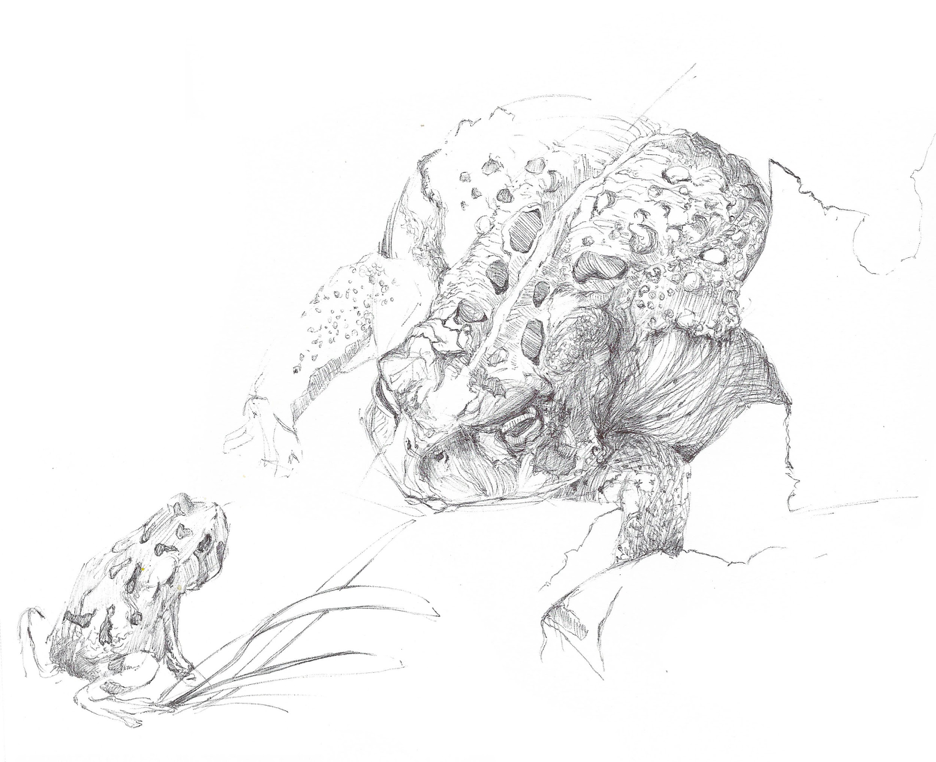

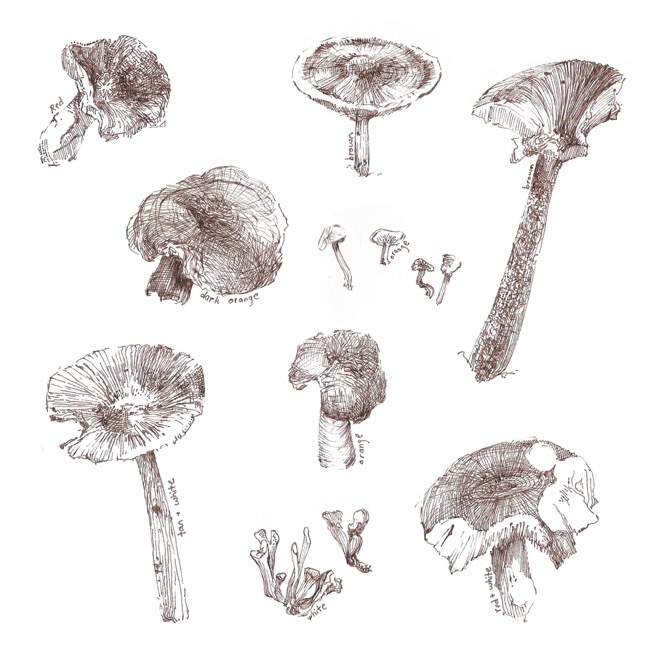

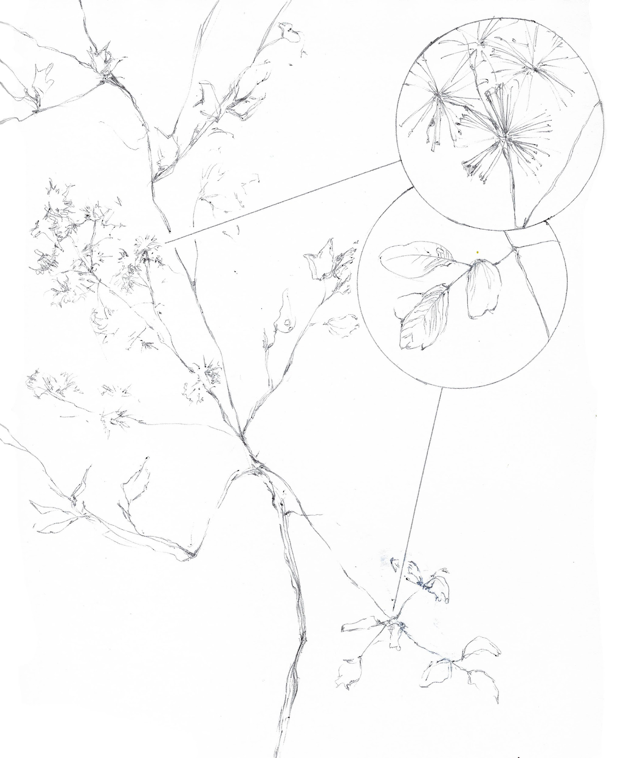

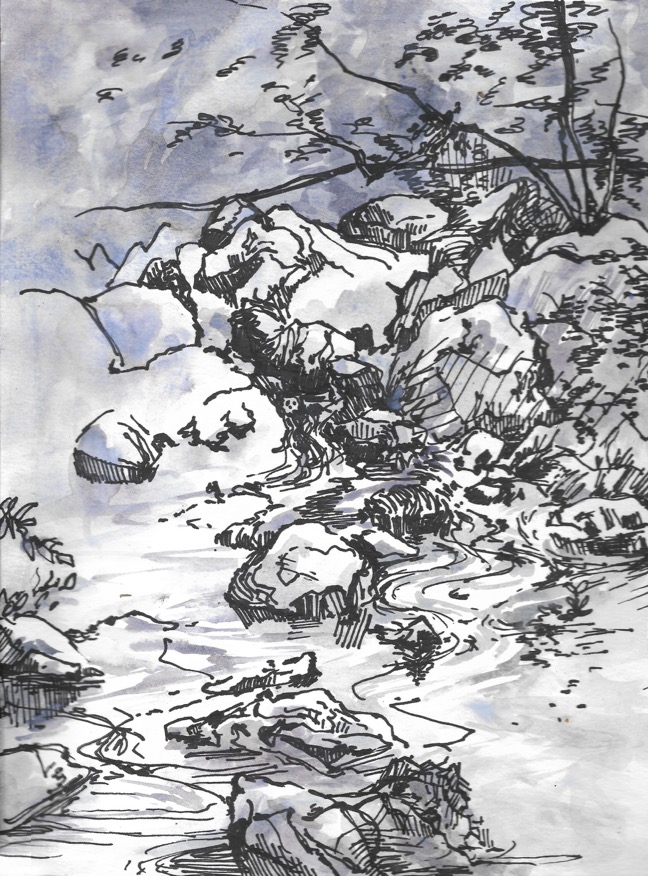

We began our hike by discussing and connecting to the native land we occupy, which welcomes us while belonging to the Wampanoag people. We then identified species of birds who nested in bird boxes of the meadow during last season, learned about owls and amphibians of the vernal pools, created land art in the pine grove, and listened to the healing sounds of the brook.

Rabbit Land Art – Made by Oliva (5)

We connected through discussing our favorite dishes of the lands we came from, our favorite species of birds from our ancestors’ lands (hummingbirds won!), and the beauty of our children’s curiosity with nature as well as love of art. We said goodbye to each other and said thank you to the land we occupy, looking forward to more opportunities to gather safely.

This group aims to spread body positivity, provide a healing connection to nature for all. To highlight BIPOC individuals in outdoor spaces is to celebrate our cultures, experiences, identities, and abilities.

The kick-off BIPOC Outdoors! Group for Mass Audubon’s Hike-A-Thon