The following post was contributed by Wellfleet Bay’s adult programs coordinator Jim Sweeney.

I recently had time to take a quick walk here at the sanctuary. The day was sunny and warm, albeit a bit breezy. But conditions were good to scout for dragonflies and damselflies around mid-day at Silver Spring pond. Most dragonfly and damselfly species are active on sunny days between 10:00am and 2:00pm, so my timing and the weather conditions were good for looking for odonata, the order to which dragonflies and damselflies belong.

I chose to walk the Silver Spring trail because it has numerous places to access the pond shore and scan the emergent vegetation for odonates (or odes in the parlance of dragonfly and damselfly enthusiasts). The trail was out of the wind and a great place to look for the diminutive damselflies that alight on trailside vegetation.

As soon as I entered the Silver Spring area, I heard the distinctive begging calls of a young bird. My attention was temporarily diverted from the trail edge to the repetitive vocalizations coming from the immediate area. I was surprised to discover a bird peering out of the nest cavity hole only a few feet away! As soon as I realized the bird was a fledgling Downy Woodpecker, the adult arrived with food and administered a meal to the young bird.

I decided to continue towards the Silver Spring bridge to avoid any interruption of the feeding of the young woodpecker. Immediately, I noticed several low-flying Fragile Forktails moving slowly in and out of the sun-dappled vegetation near the bridge. This species of damselfly is inconspicuous and easily overlooked, but it is widespread in its distribution throughout the state and found in a variety of wetland habitats.

While walking slowly along the trail, I paused occasionally and looked closely for any movement. I was checking an opening in the thickets when I noticed something move quickly on the ground. It was definitely not an ode, but I could not see what had moved so quickly and for such a short distance. When I raised my binoculars, I spotted a Fowler’s Toad blending in with the background leaf litter thanks to its cryptic coloration. This species of toad prefers sandy habitats in eastern Massachusetts. It is more often heard than seen and sounds like a bleating sheep when it gives its nasal raaaah call.

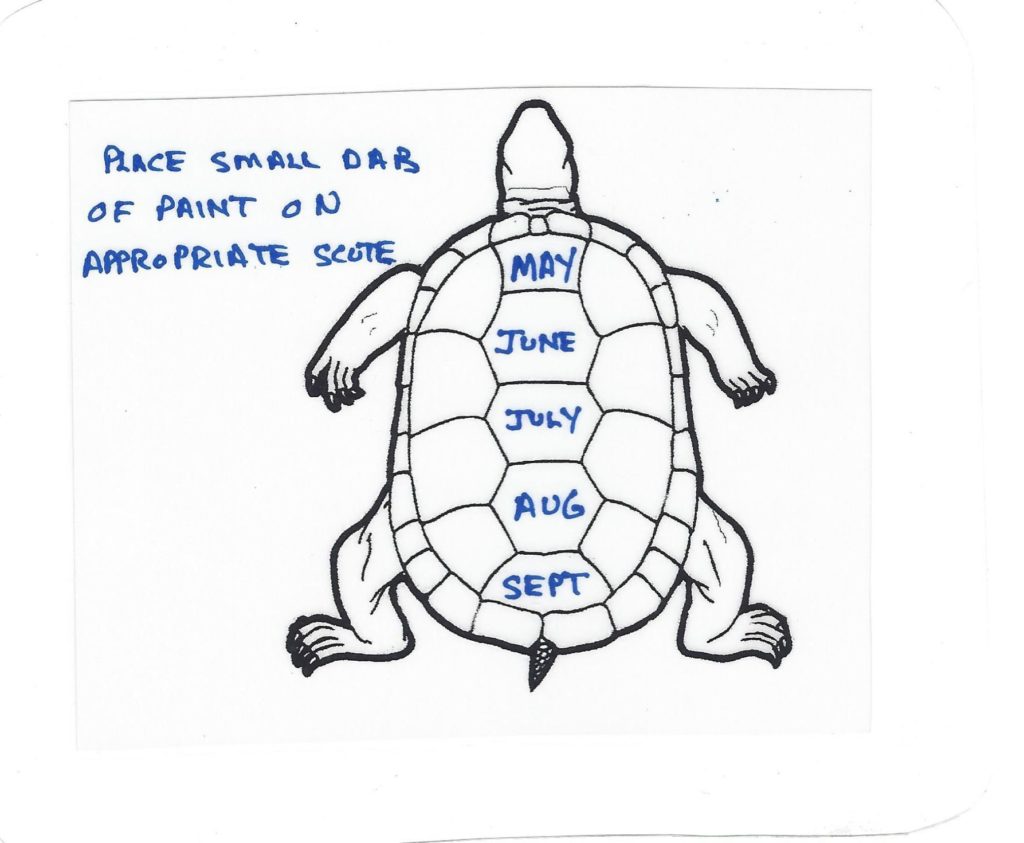

When I looked at the vegetation at the edge of the pond, I observed Blue Dashers and Slaty Skimmers, two dragonfly species that are common throughout the state. In the same general area I sighted a large red and orange dragonfly with dark patches on its wings. The Painted Skimmer is not as common as the aforementioned species, but is still regularly encountered at wetlands throughout the state. A few feet away, a Painted Turtle suddenly emerged from the water and provided a nice photo opportunity.

On one of the paths leading to the pond shore, I noticed a small dark butterfly alight on a flower at the edge of the trail. A closer examination with optics revealed a Northern Broken-Dash, a skipper that flies quickly and erratically and easily evades detection. In the same area, only about eight feet away, I noticed a Little Wood-Satyr perched on the mulch covering a portion of the trail. This woodland species of butterfly is not as flashy and charismatic as the well-known Monarch, but it is every bit as interesting if one has the opportunity to take a close look at it.

When I reached the end of the path, I decided to check the vernal pool located near the nature center. I was pleasantly surprised to see a Great Blue Skimmer alighting on a nearby cattail. This species is uncommon in Massachusetts and mostly occurs in the southeastern part of the state where it is typically found near small pools in Red Maple swamps. This species, which is more southern in distribution, sometimes makes northward incursions into Massachusetts in late spring/early summer. This individual may have arrived on the outer Cape with the southwesterly winds that occurred that day.

My goal during this brief mid-day stroll was to see a few dragonflies and damselflies at the sanctuary. I did not anticipate the diversity of species encountered on this hundred yard walk. This is what I find most rewarding about time spent in the field. The element of surprise and being in the right place at the right time can turn a quick ramble into a lesson in biodiversity!