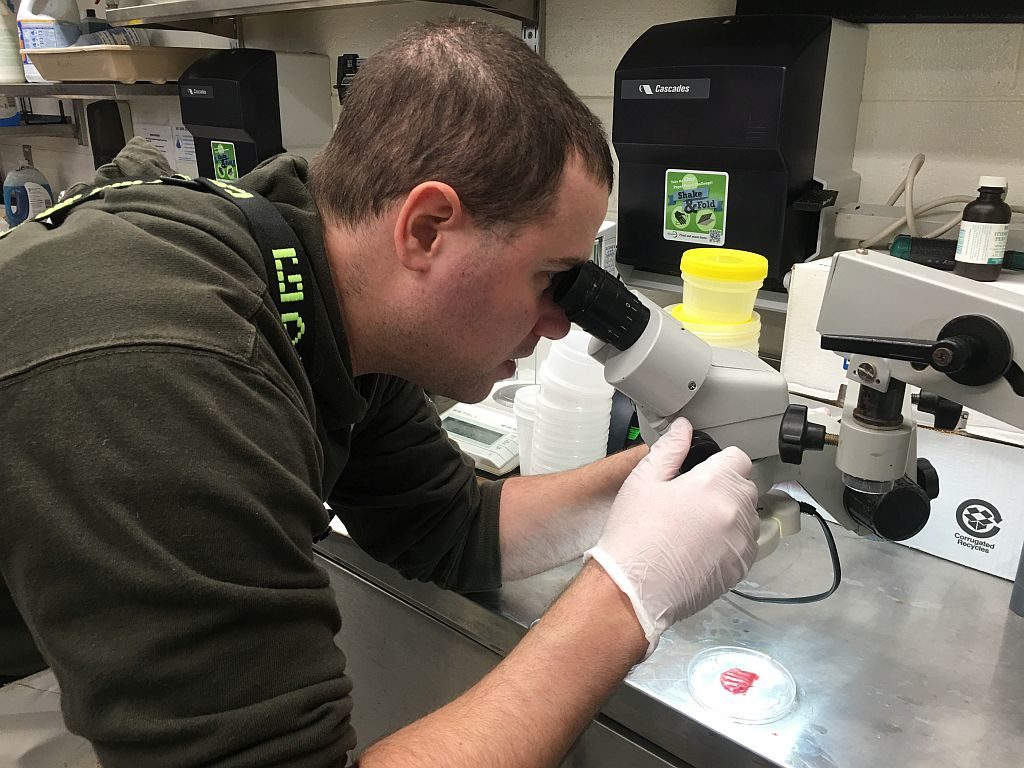

We often say that the sea turtle necropsies we conduct each Saturday in winter at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution are not for everyone. It’s a long day, there’s a lot of standing, the lab is chilly, and there are dozens of dead turtles being cut open.

But those conditions have not discouraged sea turtle volunteer Karen Strauss, a gifted photographer. She’s been documenting these sessions for seven years. In that time, Karen and her camera have captured some compelling and informative images.

One of the headlines from of this year’s sessions are the visible plastics discovered in some turtles.

There’s been growing public concern about the massive amount of plastics that end up in the world’s oceans. Karen’s pictures provide a sample of that problem and, as she says, make the abstract real. “When you show photos of balloons in a turtle’s stomach, the problem goes from something people have heard about to something more tangible.”

This year, Karen and camera were on hand to document the lobster bands found in a Kemp’s ridley’s intestines. These bands are placed on the lobsters’ claws when they go to market so they don’t use them on each other or anyone handling them.

Karen’s work also reveals the elegance of sea turtle physiology, such as the small organs that work with the larger ones, which allow the animal to perform a basic life function, such as eating. “One of my favorite structures in a sea turtle are the papillae that line the esophagus,” she says. A picture of a piece of sea lettuce trapped in the papillae of a green sea turtle’s esophagus stayed with her. ” You think about this as maybe the last thing this herbivore ate.”

Karen says she understands why some people may not find a sea turtle necropsy appealing. But instead of seeing dead turtles, Karen says she sees a special opportunity.

“Every year, we have the largest collection of juvenile Kemp’s ridleys—basically healthy animals that have died only because of cold-stunning.” The necropsy sessions are attended by academic and government scientists engaged in research which ultimately could result in better conservation for an endangered species. The sessions, she notes, are also valuable for students. “We’re training the next generation of scientists by giving them a rare experience.”

No matter how many pictures she’s taken during Wellfleet Bay necropsy sessions, Karen says it’s the chance to learn that keeps her coming back each winter. “Just when I’m about ready to say we’ve seen it all, we find something new.”

Close-up or macro photography is very challenging. To get a good picture of a turtle’s digestive tract that had a balloon string running through it, Karen had to merge 18 or more pictures together into a massive single image that showed both the full length of the intestines as well as all the detail. “Looking so closely at a turtle’s anatomy has given me the chance to learn so much more”, Karen says. ” I love to find out how things work.”

This post was contributed by Wellfleet Bay sea turtle volunteer Karen Strauss. We’re grateful that Karen works hard to document our necropsies so well and that she’s so generous in sharing her terrific work. Our thanks, too, to Carol “Krill” Carson of the New England Coastal Wildlife Alliance for sharing her picture of Karen and many dozens of others over the years.

Nice job Karen. We are very lucky to have you.

very cool!

very cool!