Given our unusually warm fall, it’s probably no surprise that it took longer for the sea turtles remaining in our waters to become cold enough to start washing ashore. In fact, this year is the latest start ever for the Cape’s annual cold-stun event.

For more than 40 years, sea turtles that feed along Cape Cod Bay in summer have become trapped by the Cape’s hook shape. It started in the 1970’s with just a few; last year it was over 1,000. As the water temperatures fall below 60 degrees, sea turtles start to slow down. When those temperatures near 50, turtles become immobile and cold-stunned, and start washing ashore.

A mid-November cool snap and gusty northwest winds finally brought in the first three cold-stunned Kemp’s ridleys around Rock Harbor in Orleans and Eastham on the 17th.

Despite the delayed start to the season, our turtle staff kept busy.

At beach parking lots and paths, new signs were posted displaying photos of cold-stunned turtles and information about what to do should you find one. Our team distributed 90 new beach signs.

As volunteers waited for the first turtles to strand, they were encouraged to reacquaint themselves with their assigned walking beaches. That’s because “winter beaches” can be dramatically different than summer beaches, with higher than usual tides and erosion that can leave very little sand to walk on. It can be even harder to follow at night!

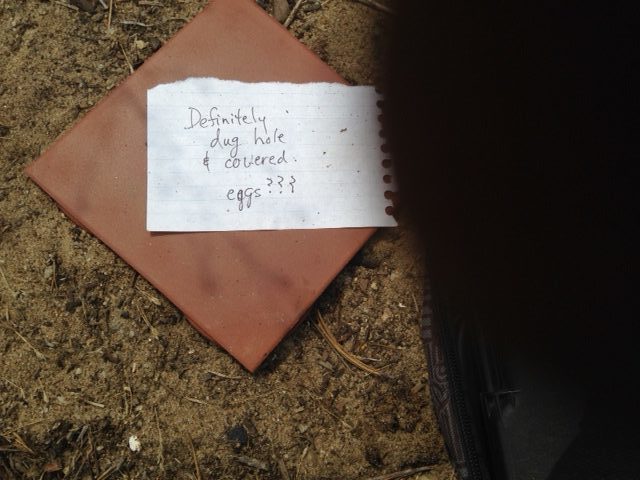

Eastham’s Boat Meadow Beach, a stretch north of Rock Harbor, is known for its irregular shoreline, frequent overwashes and marshy patches that can snag turtles. Waterproof footwear is definitely required!

We’re also thinking about more efficient ways to scour the beaches for cold-stunned turtles, especially the extensive tidal flats between Brewster and Eastham.

Recently, members of the sea turtle team led by sanctuary director emeritus Bob Prescott worked with drone pilot Steve Furlong to see if flying a drone across the beach and the flats would help detect turtles.

A recent test showed that despite flying the drone at relatively low altitudes, it was difficult to distinguish a plastic model of a small Kemp’s ridley from a patch of codium (a dark green, clumpy seaweed), so work continues on ways to improve identifying turtle-sized objects on the beach.