As I search for horseshoe crabs in the tall seagrass of the incoming tide at the sanctuary beach, it’s easy to imagine I’m in the warm waters of an ancient sea. I’m transported to the pages of the dinosaur-themed coloring books I filled in as a kid, even though 450 million years ago, when horseshoe crabs first made their debut, plants were just starting to make their way onto land, and dinosaurs were as futuristic as flying cars are now.

I continue my search, find two stray males, and wonder if our current era —the Anthropocene—could be the horseshoe crab’s last. How incredulous their ancestors would be to hear that the largest threat to their species is not an ice age or a meteor, but an upright biped unable to curb its consumption.

I squint up at a familiar silhouette on the horizon. It’s the harvester, scooping up horseshoe crabs with a long-handled net. It feels like he’s stealing from me. Every crab he gets is one that will not come to the beach next week to spawn, to pass on its DNA and get counted by survey volunteers. Instead, its destiny is to become bait for the whelk and eel fisheries.

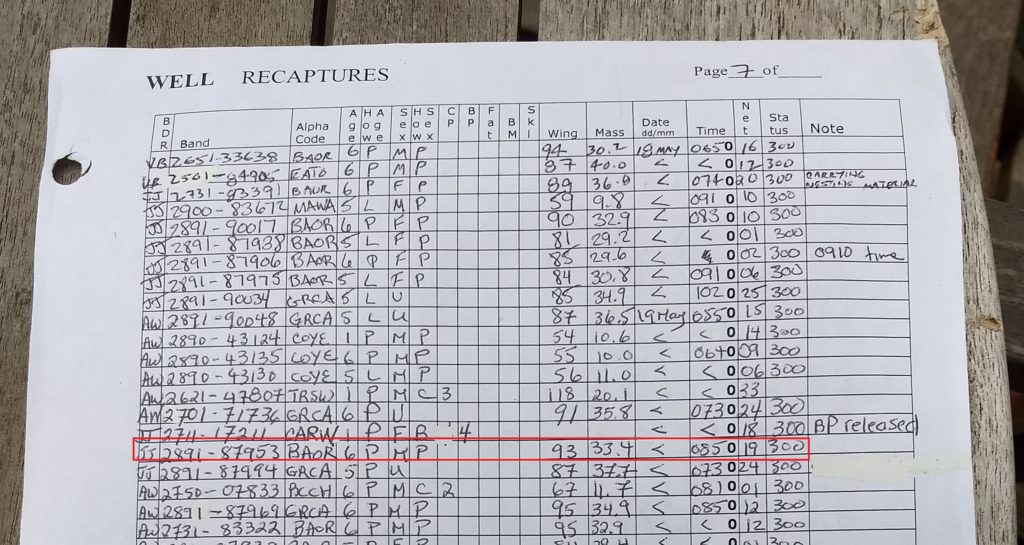

The harvester is acting perfectly within his rights. According to Mass Reg section 6.34, it is legal for permitted harvesters to collect up to 400 crabs for bait a day in Wellfleet Bay—as long as they are not taken during the week of the new and full moons when horseshoe crabs are supposed to be spawning in the highest numbers. For years the sanctuary and local shellfishermen have urged the state to impose a harvest moratorium to try to give the minuscule local horseshoe crab population a chance to recover. But despite our years of monitoring and data collection, the state so far has declined.

Down the road toward Orleans, in Pleasant Bay, it’s easier to find horseshoe crabs spawning. They appear in desperate, male-dominated hordes. It’s not an elegant affair—the males scuttle over each other, latch onto my boots or transect poles in a frenzied search for females laden with eggs. It looks like a large amount of horseshoe crabs, but I inherited a world missing 90% of its wildlife and I don’t really know what a lot of anything is.

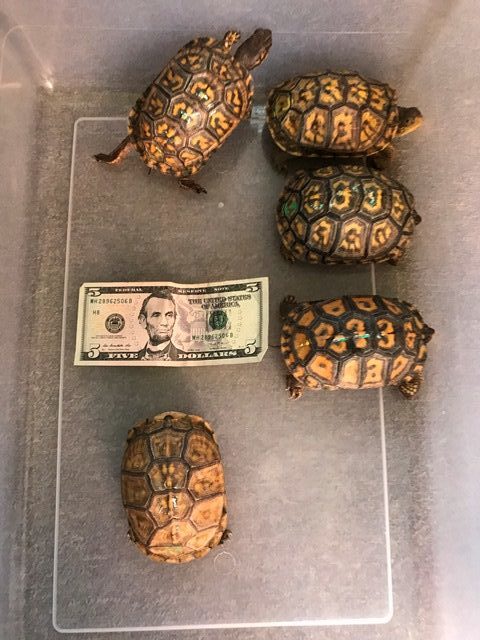

In Pleasant Bay, horseshoe crabs are targeted for blood rather than bait. Unlike the bait harvesters, biomedical harvesters can take up to 1,000 horseshoe crabs a day. While the extraction of blood is designed to be non-lethal, it is estimated that up to 30% of horseshoe crabs don’t survive the process. Further, since females are bigger, they are more likely to be targeted, likely explaining the highly male-skewed sex ratio in this embayment.

Their goal is to obtain Limulus amebocyte lysate, (LAL) extracted from horseshoe crab blood. Amebocytes (the A in LAL) are the invertebrate equivalent to white blood cells and are extremely adept at clotting around pathogens to provide defense. Health professionals use LAL to ensure the cleanliness of medical devices that come into contact with blood and injectables, including vaccines. Clearly, this stuff is useful but does the fate of modern endotoxin testing have to rest solely on a prehistoric and declining species?

Before horseshoe crabs were used for endotoxin testing, rabbits were the test subject of choice. Now, there are synthetic alternatives, the best known being recombinant factor C assay (rFC). This substitute has been approved in China, Europe and Japan, but not in the US. With more research and higher demand, synthetic options could eliminate the need for a biomedical harvest.

While horseshoe crabs are up against major hurdles, they are not without allies. Drive around the Cape long enough and you’ll see lawn ornaments in their likeness, statues of horseshoe crabs clinging to buildings, jewelry shaped like them, postcards with their image stamped on the front. Here at Wellfleet Bay, there are dozens of volunteers ready to dedicate their time to check the beach for them at high tide, willing to go out into dense marsh, down beat-up staircases, sometimes in the middle of the night, just to contribute to the study and conservation of this species.

There are many reasons to protect horseshoe crabs. One is so we can continue to benefit from their blood, and harvest them for commercial fisheries. Another is so we can marvel at the flocks of shorebirds in Delaware Bay who depend on their eggs to fuel their flights to the Arctic breeding grounds. Some find them worthy of saving for the chance to meet a living fossil. These reasons are all compelling, but my favorite reason to protect horseshoe crabs is also the simplest: because they were here first and we can.

This post was contributed by Abigail Costigan, Wellfleet Bay’s horseshoe crab field coordinator.