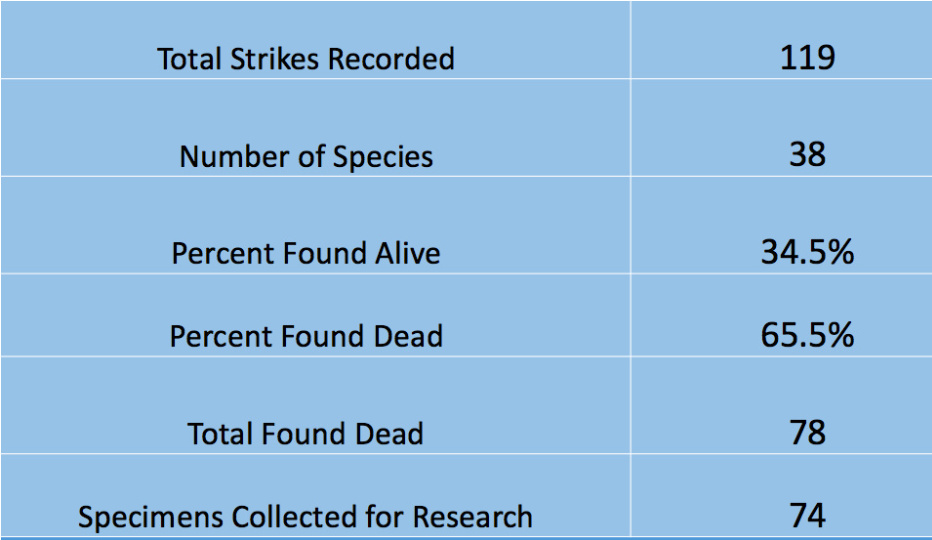

Since mid-April, a team of Mass Audubon volunteers has combed the streets of downtown Boston in search of migratory birds killed by collisions with windows. Here are some preliminary results of our first season running the Avian Collision Team (ACT).

The first statistic that jumps out is the higher-than-expected number of live, injured birds found by our volunteers. Based on what we heard from New York, Chicago, and Toronto, we had told volunteers it was highly unlikely they’d be able to save any injured birds. This ended up being far from the truth! Here’s one video of a Brown Creeper that was well enough to be released after suffering non-life-threatening head trauma:

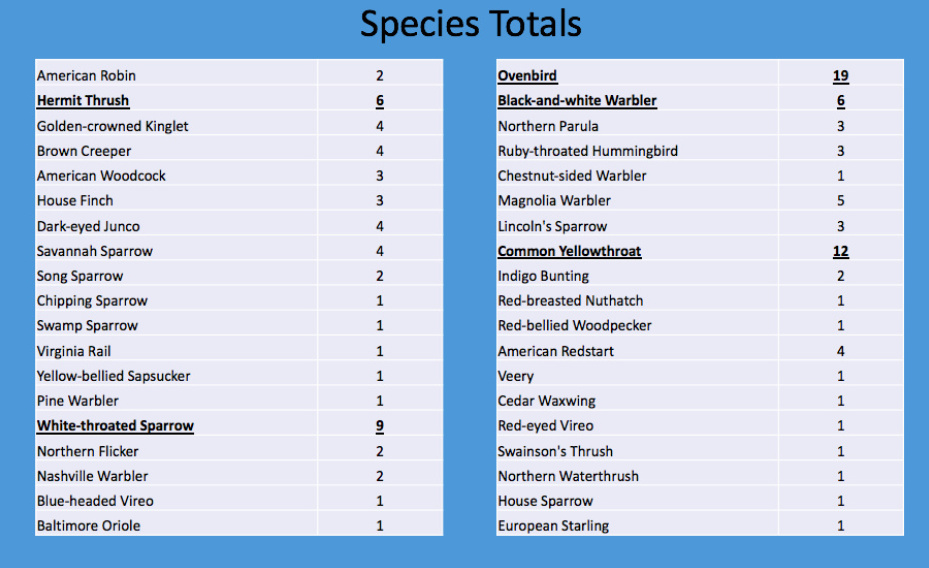

The Five “Hardest-hit” Species

Some patterns are also beginning to emerge in the species of birds we’ve been finding. Here’s the full breakdown:

The five most frequently-encountered birds (in bold text above) have something in common: they’re all low-flying migratory species, and they’re relatively common. Certain buildings also seemed to kill a disproportionate number of birds that climb trees vertically, like woodpeckers, nuthatches, Black-and-white Warblers, and Brown Creepers. Other cities have reported similar species profiles with an emphasis on common migratory birds that fly low and weakly.

The Bottom Line

A few dozen people surveying a thin slice of the city for an hour or so per week found 119 window-struck birds of 38 species.

Other cities report that certain seasons have up to four times the number of strikes than others. The wide variability of window strikes makes it difficult, after just one season, to make broad statements about how many birds die from collisions in Boston annually, or establish how Boston shapes up compared to other cities. That said, our numbers fall roughly into the range reported by similarly-sized programs in other cities, like Baltimore, Detroit, and New York.

After accounting for scavengers, industrious building cleaners, and low volunteer detection rates, it’s estimated that only 10-20% of window strikes on a given route are actually recorded. That makes our numbers all the more sobering, especially considering our volunteers covered less than 1/50th of the street area of Boston.

That said, window strikes by themselves may not drive bird declines in Massachusetts. Window strikes are an additional stressor, however, on top of a laundry list of human-caused threats to bird populations. In today’s world of climate change, habitat loss, and invasive species, every bird counts– which is why window strikes are worth understanding.

Cities Are Only Part of the Problem

Outside the study areas in Downtown Boston, our volunteers reported many casualties even without focused searching. Their findings emphasize what other studies already suggest: window strikes are at least as much of an issue at single-family homes and low-rises as they are at tall urban buildings.

The good news is that there are lots of ways to make your home or office windows bird-safe. Here are some tips:

Screens on windows are the cheapest and perhaps simplest option: they break up reflections and also provide a springy barrier that collision-bound birds can bounce off of.

Where screens are impossible, consider buying or building an Acopian Bird Savers (hanging lengths of bird-deterring string). Learn how to build your own here!

Window decals only work when spaced less than 2” apart vertically and 4” apart horizontally, but when used correctly, they’re another great option. Certain kinds are transparent to human eyes, so even narrowly-spaced ones won’t interrupt your view.

Installing UV-reflective patterned glass like Ornilux is extremely effective, and

by far the most discrete option– but also the most expensive.

Finally, turning unneeded lights off

at night helps conserve energy and avoid drawing birds into strike-prone areas.

(Disclaimer: Mass Audubon has no affiliation with any of the above vendors).