The following post was contributed by UMass researcher Patty Levasseur.

For many years, Wellfleet Bay has worked tirelessly protecting diamondback terrapin nests and releasing hatchlings to help this threatened species. Even so, the health and size of the terrapin population in Wellfleet Bay remains mostly unknown.

To answer some of these questions, we began a mark and recapture study last spring. In May, 2018 we began capturing diamondback terrapins at two locations: Chipman’s Cove, near Indian Neck, and the Run, off the sanctuary’s beach, using a standardized survey protocol. Captured terrapins are also injected with a PIT (Passive Integrated Transponder) tag just under the skin in their rear left thigh, which contains a unique number identifying (marking) that individual. Lastly, they are weighed, measured, aged, sexed, examined for any injuries, photographed and released back into the water.

In our first year, we captured only 46 terrapins in Chipman’s Cove and 159 terrapins in the Run for a total of just 204 terrapins, much lower than we expected. We also had a lower-than-expected recapture rate, with zero recaptures in Chipman’s Cove and only 5 in the Run. These low numbers were not enough data to achieve a confident population estimate of terrapins at either location.

Why was our capture rate so low? Based on years of knowledge from local experts, we know that lots of terrapins are found at these two sites in the spring and early summer. Often, just prior to conducting a survey, we would see many small heads pop up on the water’s surface as turtles swam into the study site. So why couldn’t we capture them?

We decided to review our survey protocol. But first, a little background.

In order to conduct an effective population study, you must collect data on exactly where you search for your target animal and where you capture each animal. This is usually achieved by using a handheld GPS unit that uses satellites to pinpoint your (and the turtle’s) exact location and keeps track of where you move. In formulating our survey protocol, we wanted to minimize complicated GPS use, thinking it might distract from catching all the turtles we would encounter. Instead of taking GPS points, we opted to use the GPS only to track where we moved by selecting small, pre-defined study spots within our overall survey area so that we would know exactly where we had looked and where each turtle had been captured without the need of stopping to take a GPS point for each turtle.

However, what we learned is that limiting where you can search for turtles also limits the number of turtles you could encounter! We also learned that navigating to each small survey site actually required more time using the GPS and left less time for surveying for terrapins.

So we revised the protocol by allowing freedom to survey the entire study site, using the GPS to track the areas where each person surveyed and to take point locations of where each turtle captured.

But there was a new challenge. How would we ensure we could associate each individual turtle with its capture location? We solved that problem with…pillowcases!

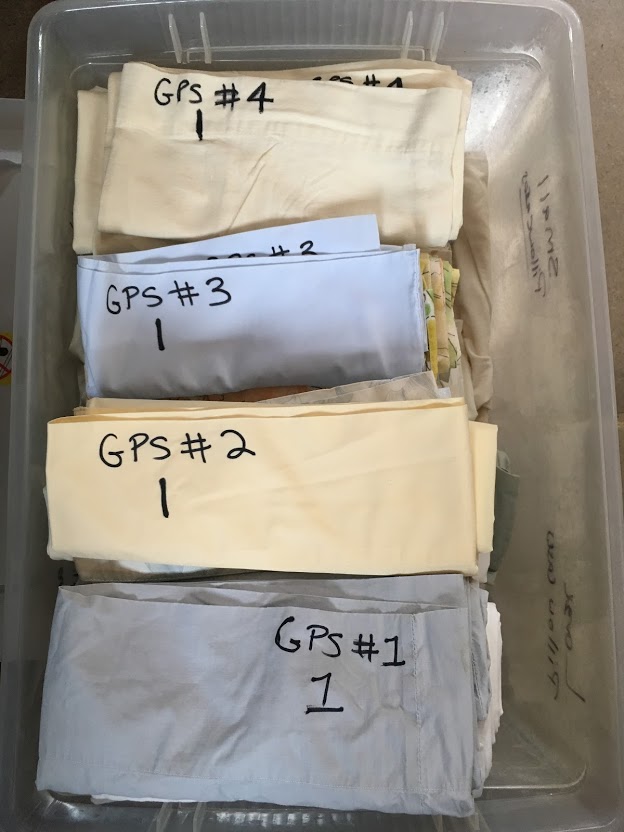

Thanks to some very generous Wellfleet Bay volunteers, many pillowcases were donated to this project. We numbered each pillowcase with permanent marker (the cases were numbered 1, 2, 3, etc.) that would be brought out with the surveyor. It would work this way: When the first turtle was captured, a GPS point would be taken and recorded on the GPS device as waypoint 1 and the turtle would be put in pillowcase number 1. The surveyor would continue searching and when the second turtle was caught, it would be recorded as GPS waypoint 2 and put in pillowcase 2, and so on. Now we had a safe and effective way to keep track of each turtle’s location! Our survey protocol was revised and ready to try out for the 2019 season.

In May of 2019, we began the second year of the population study using our new protocol. Our initial fear of over-complicated GPS use faded shortly after the start of the season, as the new pillowcase method actually involved less GPS use and more survey time than our old method.

The results have been great! So far this season, we have captured 236 terrapins in Chipman’s Cove and 251 terrapins in the Run for a total of 487 terrapins! Even more exciting, we have recaptured 27 individuals in Chipman’s Cove and 38 individuals in the Run! Our capture rate increased 139% from 2018 to 2019, providing strong support for our revised protocol. Of course, it’s not just the protocol that achieved these captures, it is also the keen eyes, and quick reactions of the dedicated and skilled research staff here at the sanctuary.

Based on these numbers, we appear to have enough data to analyze and achieve a baseline population estimate of terrapins in Chipman’s Cove and the Run. Achieving a population estimate in two small locations will not tell us the population size of the entire bay, but it is a critical and exciting first step. In the years ahead, we hope achieve population estimates at more locations, building site specific population profiles in an effort to reach a terrapin population estimate for all of Wellfleet Bay.

This post was contributed by Patricia Levasseur, a graduate student at UMass, Amherst pursuing a Masters of Science degree in Wildlife Conservation Biology via an externship with Mass Audubon Wellfleet Bay. Patty has ten years of field research experience ranging from headwater stream amphibians in Oregon to brown tree snakes on the island of Guam to Piping Plovers, Blanding’s turtles, red-bellied cooters, wood turtles, blue-spotted salamanders and diamondback terrapins. She lives in Acushnet, Massachusetts with her husband, 2 dogs and 8 chickens.

Hello to all, it’s genuinely a good for me to pay a uick visit

this web site

Amazing and Useful article. thank you