Salt marshes, like oceans and forests, are critical buffers from the effects of a fast warming planet. Healthy salt marshes capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store carbon in spongy peat beds that form the base of the marsh. A thriving salt marsh can store at least three times as much carbon as an equivalent area of mature tropical rain forest.

Salt marshes do more than store carbon. They provide food and shelter for countless animals, including birds and many commercially important fish, and they reduce flooding and erosion by absorbing excess floodwater and slowing waves. But that’s only if they’re reasonably healthy and can keep up with rising sea levels.

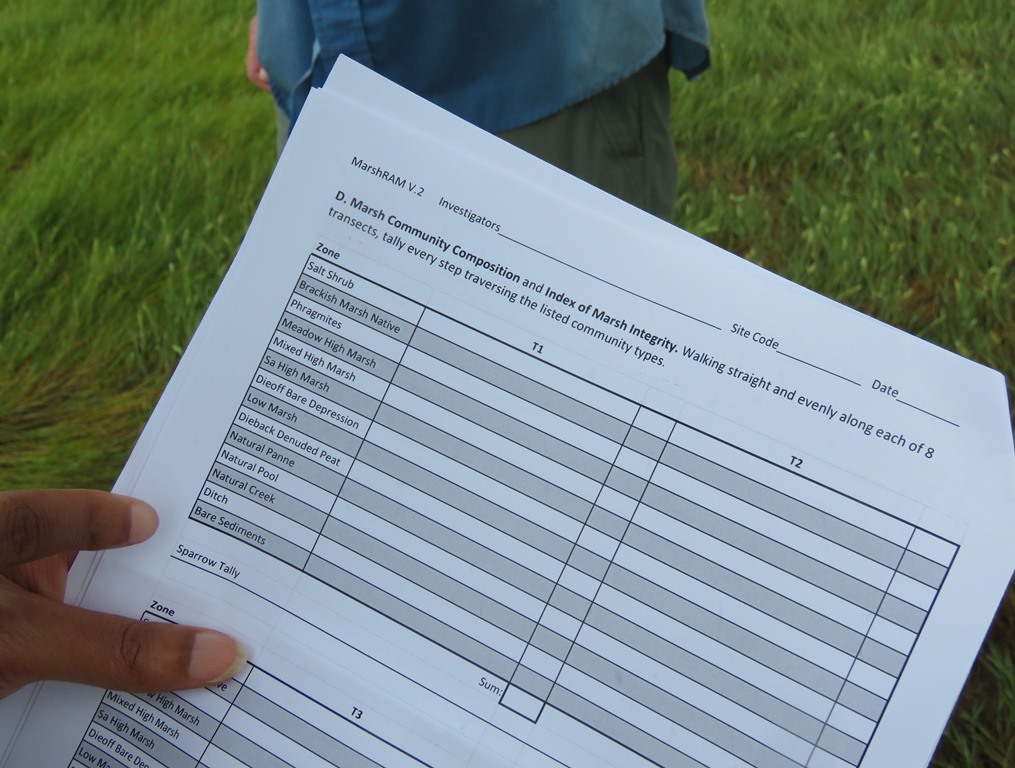

On an August morning, Mass Audubon’s Climate Change Adaptation Ecologist, Dr. Danielle Perry, and her volunteer assistant, Thomas Eid, began to pace out a series of randomly chosen 200-foot survey lines, also known as transects, to study various plant species and their locations, the peat condition that supports the marsh, and even the upland surrounding the salt marsh.

This is a pilot survey, one of five Dr. Perry is conducting at different salt marshes at Mass Audubon sanctuaries, including Barnstable’s Great Marsh at Long Pasture. The goal is to determine to what extent each marsh is being impacted by climate change and sea level rise.

Is Wellfleet Bay’s salt marsh at risk? One way to answer the question is to look at the cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), a species from the low marsh which floods twice a day at high tide. If cordgrass is found in the high marsh, which floods only periodically, then it suggests sea levels are rising high enough to promote cordgrass encroachment into the high marsh.

“There are some good signs here,” Dr. Perry notes. “There’s healthy cordgrass in the low marsh (the part of the marsh flooded by high tide twice a day), but there’s also evidence of cordgrass encroaching on the high marsh ,” she adds. She says cordgrass displacing salt marsh hay (Spartina patens) in the high marsh could lead to loss of the habitat critical to breeding birds, such as the Saltmarsh Sparrow.

Other worrisome climate vulnerability indicators are the presence of man-made ditching (once believed to control mosquitoes), bare patches of peat, and low spots—areas where peat is subsiding.

Such conditions can increase the risk of erosion and flooding stress, which can severely degrade the marsh.

If salt marshes are to survive sea level rise they need to adapt through landward migration or what’s known as vertical growth.

Landward migration involves marsh movement into upland areas. Dr. Perry notes that Wellfleet Bay’s marshes have some room to do this but not as much as the Great Marsh in Barnstable, which has a lower shoreline profile and less development. “Some of the upland areas at Wellfleet lack a gradual slope that would allow the marsh to move landward to keep up with sea level,” she says. Vertical growth means increasing the height of salt marshes through added sediment and helping marshes keep pace with current and rising sea levels.

Dr. Perry hopes to complete her pilot study this fall and eventually survey the remaining salt marshes at Mass Audubon’s coastal sanctuaries next summer. The information will be used to inform and prioritize climate change adaptation projects for Mass Audubon sites. “Some of those projects will involve relieving some of the flooding stress marshes are under or identifying specific sources of nutrient pollution that might be controlled or eliminated to protect marshes,” she says.