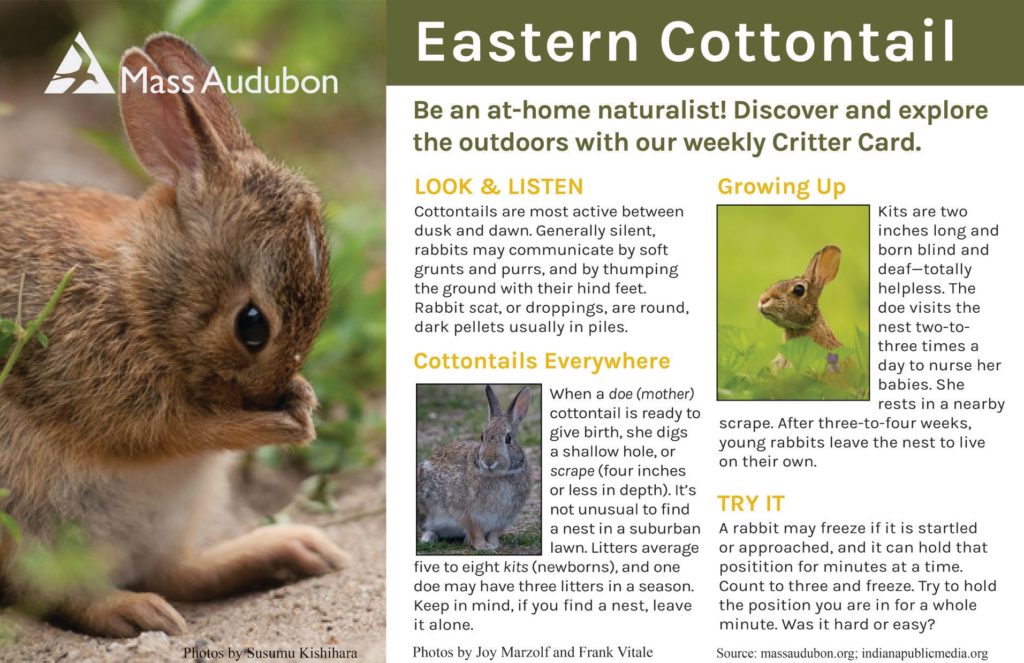

The Eastern Cottontail, Sylvilagus floridanus, is the most common rabbit in North America. They range from Canada to South America and from the east coast to the Great Plains in the central United States. Living predominantly at the edge of open areas such as fields or farms, cottontails are generalists, able to survive in a wide variety of habitats. They can even thrive close to human activity, often popping up in lawns and sheltering under shrubs.

While the Eastern Cottontail has variety in their coat color, nearly all individuals sport a reddish patch on their nape (the back of their neck), and every individual carries its namesake: the white, cotton-ball-like tail. Distinguishing the Eastern Cottontail from its rare cousin the New England Cottontail is difficult. The only coat difference is that 50% of the latter have a dark spot on their foreheads. Normally, distinguishing the two species requires examination of the skull structure.

The Eastern Cottontail is in the family Leporidae, which is known for rodent-like teeth and delicate lattice bones in their skull. There has been heavy debate on where Leporidae belongs on the phylogenic tree. Previously in the Order Rodentia, a study confirmed they should be classified separately based on the structure of their teeth. This study was met with strong resistance, but was so highly supported, it prevailed. An additional study looking into the genetics of the Eastern Cottontails suggested they may be more closely related to some primates rather than rodents!

A healthy Eastern Cottontail population density should be around three to five rabbits per acre, kept in check by their natural predators. Left to their own devices, cottontails overpopulate, leading to overgrazing, disturbing gardens to the point of destruction, a high risk of disease, and out-competing other species who need the same habitats. Natural predators, such as coyotes, foxes, birds of prey, and snakes help control the cottontail population.

A female Eastern Cottontail may have three-to-four litters in a season. Breeding season runs from February to September. Each litter will be weaned within three weeks, out of the nest and independent within seven weeks, and ready to breed at three months old. This is an important ability, as cottontail rabbits play a crucial role in the food web. Rapid reproduction helps to support predators that rely on the Eastern Cottontail as a food source.

The milk of a female Easter Cottontail is the most protein-rich milk currently known, and is also quite fatty, to boot. It has a whopping 12% of fat and 10% of protein (compare to humans at 3% fat and 0.8% protein), making it rich and full of essential nutrients for the newborns, or kits. This potent milk allows females to nurse their young for only a couple minutes a day. The rest of her day, she will spend foraging and sheltering away from her kits. Because rabbits live on the ground, in shallow scrapes, this is essential for kit survival.

The Eastern Cottontail practices coprophagy. This means that they are one of the species that consume cecotropes. Cecotropes are fecal pellets that have passed once through the digestive tract of rabbits. However, these pellets are expelled and consumed again for a second pass through the digestive system. Cottontails thus increase the extraction of nutrients. So… they are essentially eating their own scat, for their health.

What can you do for rabbits? Plant a few extra veggies in your gardens and let those rabbits have a snack! While it is true that they can become destructive when not kept in check, a rabbit taking a carrot top or beet greens from your garden is a sign of a healthy ecosystem. “One to harvest, one to grow!”

Learning Tools from Mass Audubon

Read all about cottontails.

Learn about rabbits in your yard and garden.

Looking for More Resources and Activities?

Watch this video to learn what to do if you find a rabbit nest in your yard. If you care, leave it there!

Read about cottontails and use the data to do some “bunny math.” Great for all ages, teachers, and parents.

Explore iNaturalist and learn about cottontails.

Learn with this lesson about rabbits, and then take the quiz (may require online subscription).

Dig deeper into the diversity of hares and rabbits.

Watch this kid-friendly video about rabbits from around the world.

Watch this video of a cottontail kit being rehabilitated.

Print this page for more quick facts about cottontails.

Submissions

“We have them in our backyard. The other day I was working in the front garden when all of a sudden 6 or 7 of them FLEW out of there!” – Facebook participant

What’s Next?

What would you like to learn about from your backyard? Let us know in the comments.

Stay tuned for the next Critter Card coming out on Monday, by email and Facebook.

Connect With Us

Would you like to be added to Lisa Hutchings’ VIP email list? Receive special resources such as nature slideshows and educational tools for at-home learning. Send an email to [email protected] requesting to be added to the VIP list.

Thanks to our Critter Card Fans

Love the cards. They will be great in the classroom. – PreK teacher

It is great to have your Critter Cards as a weekly surprise. It makes us feel so connected to Joppa Flats Education Center. Congrats to you and your team for always stepping up and delivering in any and all circumstances. – parent