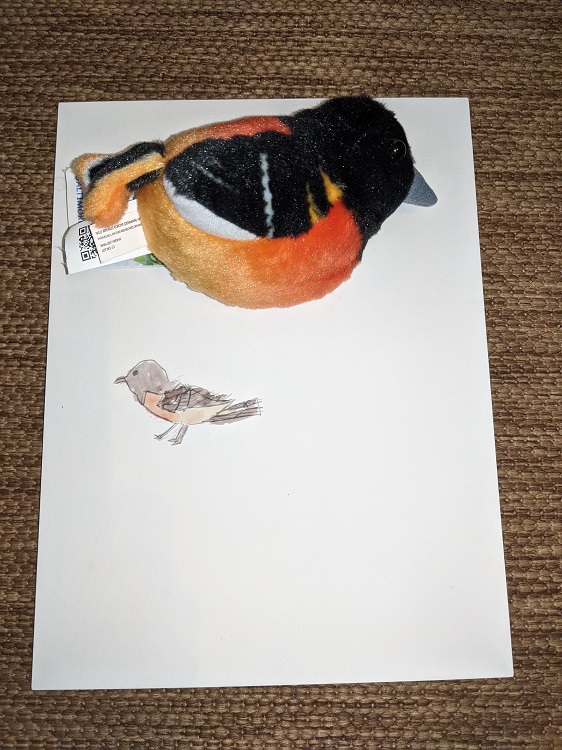

There’s no getting around it: Poison Ivy season is here to stay. As its leaves come out this spring, utilize our Critter Card to help you identify Poison Ivy so you can react to it appropriately and prevent it from hurting you. While Poison Ivy isn’t anyone’s favorite plant, it is a common one that you should feel confident identifying. Being able to do so will help lower your risk of a negative encounter.

Identification

There are two species of Poison Ivy native to the eastern United States: Eastern Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) which climbs like a vine, and Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii) which grows like a bush. Because they are able to cross breed, there is a variety of structures among individual plants: they may take form as a bush, a vine, or anything in between. Vines often overtake trees, killing them and providing foliage when they no longer can.

Poison Ivy vines climbing on a tree – Chaffee Monell

Poison Ivy bush – Chaffee Monell

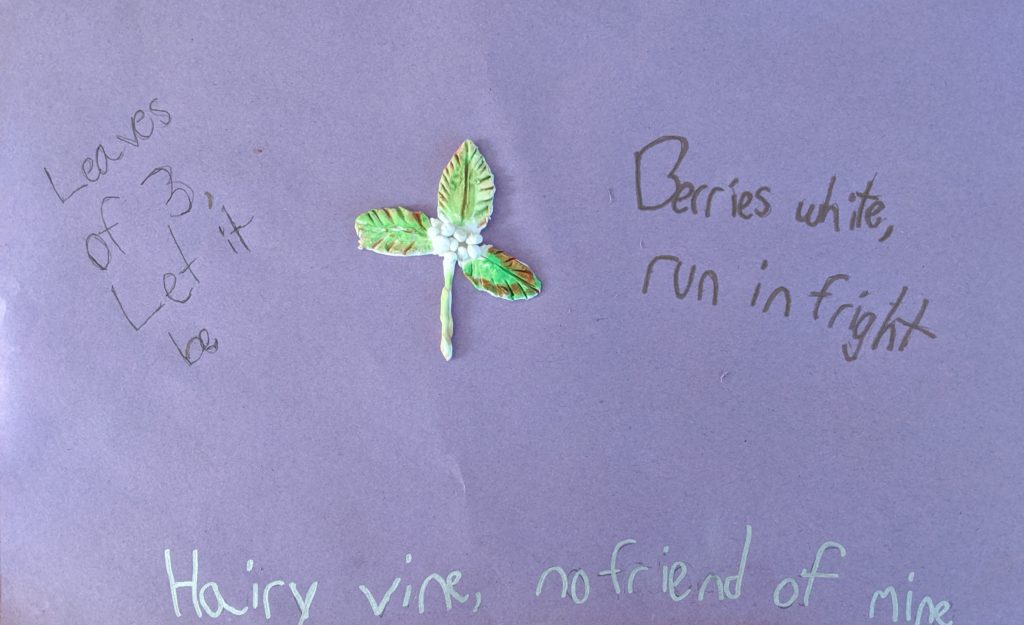

Despite the varying growth patterns, there are common characteristics that will give this plant away. You will always see one leaf made up of three leaflets, all connecting to a reddish colored stem. The middle leaflet will have a longer stem than the ones on the sides. Leaflets may appear shiny with soft edges, and some or all of them may have a glove-like shape. Vines will appear hairy with roots sprouting all along them.

Note the three leaflets that make up each leaf – Chaffee Monell

This “hairy” vine is actually made up of Poison Ivy roots -Lisa Hutchins

How it Works and What to Do

Poison Ivy is not technically a poisonous plant. But it contains a sticky oil called urushiol, which is very potent: one quarter of an ounce could produce a rash on every person on the earth. The oil adheres very quickly to anything touching it, including skin, and can be long-lasting if not promptly washed off. If you come in contact with the oil, your rash may not show up for a few days, but it will last roughly two weeks.

Urushiol exposure causes urushiol-induced contact dermatitis, where skin becomes itchy and develops blisters. The dermatitis is the body’s way of fighting off the irritating oil. This allergic reaction primes the body to defend itself, and that means that subsequent exposures you may have will result in more vigorous and efficient reactions; in other words, each time you get a rash, it is likely to be worse than the last.

If you’ve been in contact with Poison Ivy, you will first want to flush your skin with cold water for a couple of minutes. This will help to remove and dilute any oil that’s stayed on your skin. After flushing, wash the area with soap (dish detergent is great at cutting the oils) and water. Other options include using products such as Tecnu, which is made to wash the oils off our skin and clothes.

Dealing with a reaction? Don’t cover it with a bandage! Do let the infected area breath and dry out. Use anti-itch lotions such as calamine lotion to keep the itchy feeling at bay. Running hot water over your skin can also alleviate the itching sensation for some time.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is Poison Ivy active all year long?

Yes! In the late autumn and throughout the winter, when the leaves have fallen off, the stems, roots, and vines will all still contain urushiol. - Can my dog or cat give me Poison Ivy?

The short answer: yes. Dogs, cats, and other pets that come in contact with Poison Ivy can carry the oil on their fur, so when you touch Spot you can get it from her. Simply wash your pet with pet-safe shampoo, or use baby wipes to clean off their fur if you know they’ve touched Poison Ivy. Most animals with fur won’t get a reaction to the urushiol, but bare spots such as noses, bellies, and ears can be susceptible to irritation. - Is Poison Ivy Dangerous?

Usually a reaction to Poison Ivy isn’t dangerous, but it can be obnoxious or uncomfortable. In extreme cases, people can experience a full body rash, rash around the eyes, extreme blisters, or other reactions consistent with anaphylaxis. Severe reactions should be referred to your doctor or emergency services. - Does scratching spread a Poison Ivy rash?

Once the oil has been washed off the skin, contact with the rash, including scratching, does not cause the itch-inducing oils to spread. However, scratching could lead to a secondary infection that’s equally unpleasant, so it’s best to resist the temptation. Additionally, Poison Ivy oil can get under your fingernails, which you will then spread to other parts of your body if you scratch them. Don’t forget to scrub under your nails! - Does Poison Ivy stay on my clothes?

Yes! And it can be spread to your skin from your clothes, even many months after exposure. If you’ve been in contact with Poison Ivy, promptly wash your clothes in hot water with detergent. You may have to wash your clothes more than once or add Tecnu to your wash. - Can I be immune to Poison Ivy?

Yes you can. Many people have an immunity to the oils from Poison Ivy. That doesn’t mean that you should touch it whenever you like! Most people who have had immunity will become allergic after many encounters with the oil, or after an especially involved exposure to it. Best to steer clear regardless.

Dealing with Poison Ivy on your Property

TThe best way to remove Poison Ivy is head on. Completely cover yourself up in clothing, including long sleeves, pants, gloves, and even a hat if you’re dealing with vines. Dig the plant up, getting as much of the root as you can. Bag it up in a garbage bag and then put it out with the trash. Getting as much of the root as possible is essential to ensure the plant doesn’t re-sprout. To do this, dig at least six inches into the ground when removing roots.

Another great option is to rent goats! Some goat farmers will loan out goats to clear vegetation. Goats and beef cattle are great at processing difficult plants and weeds and will readily eat Poison Ivy when it’s available.

Lastly, manage the plant. If you enjoy the color and look of Poison Ivy, or want to keep it around for birds and herbivores who aren’t affected by the oils, consider keeping the population in check. But, Poison Ivy is a productive and successful plant, and letting it grow will allow it to overtake trees and plots of land on the forest edge. If you decide to keep it around, it’s best to manage it – carefully – by removing new seedlings and cutting down plants before they become too large.

The two most important things are not to use herbicides or fire! Herbicides can kill surrounding plants and animals. Fire may kill the plant, but the urushiol can remain in the smoke and air during burning and can cause very unpleasant irritation to your eyes, throat, respiratory system, and skin.

It’s not all Scary!

Poison Ivy isn’t a bad plant! It has natural beauty, it’s native to the eastern United States, and it plays an important role in the ecosystem, acting as a natural food source for many wild animals. A variety of birds are drawn to its berries, especially in the winter when food is scarce. Pollinators buzz to its flowers, and deer, along with other herbivores, eat its leaves and woody stems.

In the autumn, leaf peepers, homeowners, and others venturing outside can enjoy the bright colors of Poison Ivy. The leaves turn red, orange, or yellow, and the berries will ripen from pale green to white.

Did you know? Poison Ivy is related to mangoes! Whether this helps your appreciation for Poison Ivy, or ends your love for mangoes, it’s a fun fact. Both plants produce urushiol, which is why humans can have reactions to mango skin.

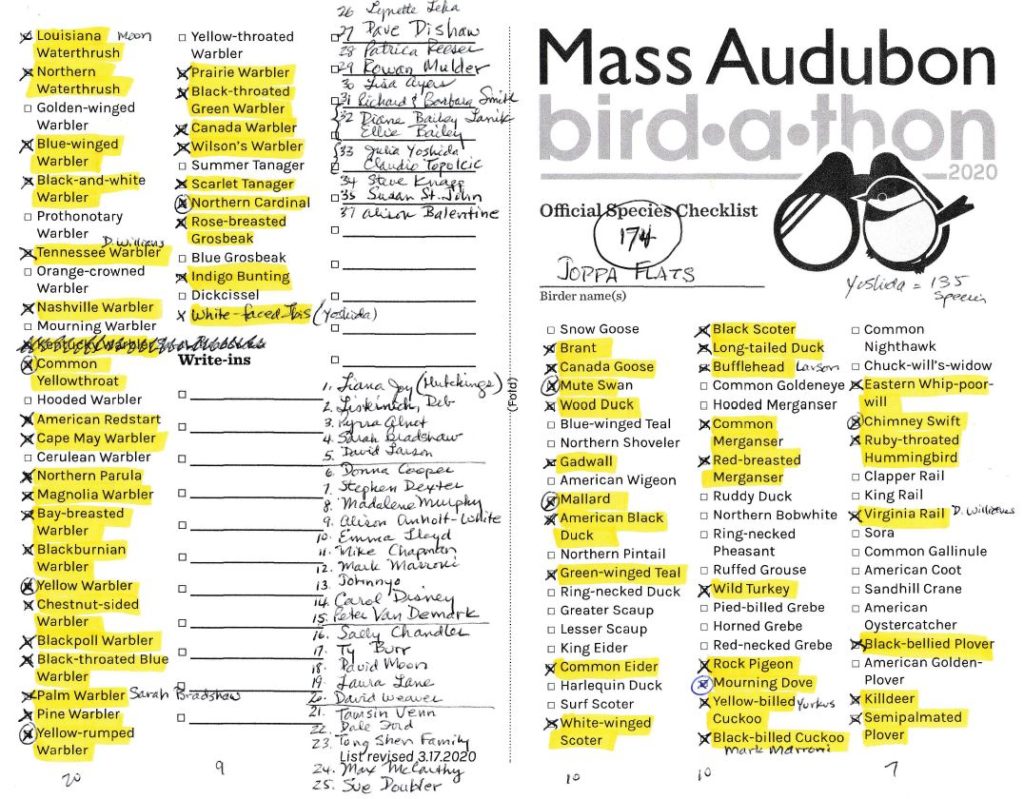

A special shout out to Joppa Flats Teacher Naturalist, Phil Smith, for the great suggestion of covering Poison Ivy in our Critter Cards.

Learning Tools from Mass Audubon

Read about the Many Faces of Poison Ivy.

Learn about these tips for managing Poison Ivy.

Looking for More Resources and Activities?

Research Poison Ivy on Go Botony.

Watch this kid-friendly video about Poison Ivy precautions on Botony for Kids.

Watch this video about how to treat and avoid Poison Ivy for adults from the Mayo Clinic.

Read these six facts about Poison Ivy that you may not have known.

Increase your knowledge with this list of fascinating facts about Poison Ivy.

Submissions

“I make a tea with Sweet Fern. It’s only good for external use, but works very well! Keep it in the fridge so it’s nice and cool when you put it on the rash. Works for Poison Ivy and bug bites” – Facebook User

“I think Poison Ivy is very pretty when the small bronze-leaved plants just emerge, forming a little forest with the Star Flower and other small early wild flowers and leaves. Photo attached. I once had a couple of sheep who liked to eat Poison Ivy!” – Heather Miller

“When I started at the banding station back in September 2002, I cam armed with some advice from a friend. Wash with dish soap since it’s formulated to remove grease and oil. The oil will be gone, and you’ll be smelling lemony fresh!” – Ben Flemer, Joppa Flats Bird Banding Manager

What’s Next?

What would you like to learn about from your backyard? Let us know in the comments.

Stay tuned for the next Critter Card coming out on Monday, by email and Facebook.

Connect With Us

Would you like to be added to Lisa Hutchings’ VIP email list? Receive special resources such as nature slideshows and educational tools for at-home learning. Send an email to [email protected] requesting to be added to the VIP list.