Red-tailed Hawks (Buteo jamicensis) are a common hawk species in Massachusetts. Sometimes referred to as the “highway hawk,” Red-tails are often seen perched along the highways and hunting their small grassy edges and medians. By doing this, they are adapting to anthropogenic (man-made) factors that affect the environment and hunting in habitat disturbed by humans. It’s likely that you’ve seen these large birds along highways or near farms, fields, meadows, open forest plots, and suburban neighborhoods.

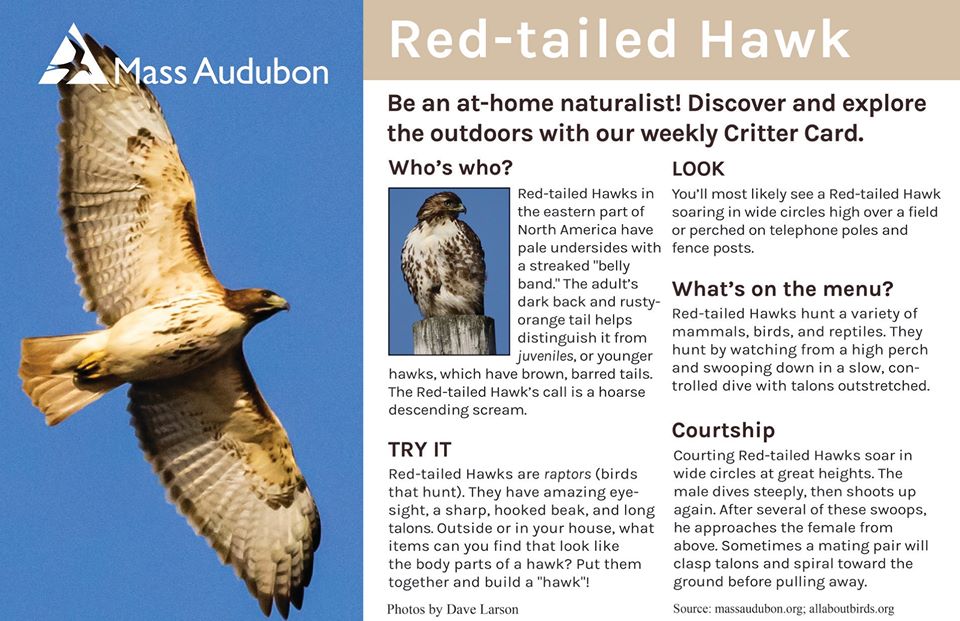

Look for Red-tailed Hawks perched up high, using their keen eyesight to hunt. Searching for prey such as rodents, birds, and snakes, Red-tailed Hawks rely on seeing tiny movements far below. Like most birds, Red-tails have binocular vision, meaning they keep focus on their prey with both eyes. Many predators, including humans, have binocular vision; our field of view is compromised in order to give us depth perception. A Red-tailed Hawk can see a mouse from 100 feet in the air, and dive at nearly 120 mph to catch it. Accuracy, which depth perception allows, is essential to scoring a meal.

Listen for Red-tailed Hawks around these areas as well. Their call, which is a loud, descending scream, is distinctive once you’ve heard it. In fact, you might even recognize the call from movies. That’s because the call of the Red-tailed Hawk is often dubbed in for eagles or hawks. If the natural call of an onscreen raptor isn’t really all that impressive, a Red-tailed Hawk’s piercing and powerful cry just sounds better!

Red-tailed Hawks don’t present sexual dimorphism in plumage; that is, both females and males appear the same. Red-tailed Hawks do, however, display a vast variety in their plumage. There are 14 subspecies of Red-tailed Hawk, each with distinctive plumage from extremely dark to very light and by range.

Red-tailed Hawks are sexually dimorphic in size, with the female one third larger than the male. They both reach sexual maturity at three years old. In the spring, they attract mates by performing courtship flights. Soaring in circles high above the ground, a male will dive steeply before turning and climbing steeply back into the air several times over. If she is receptive, he will fly above her, reaching out to make contact with his feet. Much like eagles, Red-tails may grasp one another’s talons and free-fall, spiraling about, and even mating, before releasing each other and pulling away from the ground.

Successfully mated pairs of Red-tailed Hawks will mostly remain monogamous, staying together for years and protecting the same territory, until one dies. These birds reach ages of 10-15 years (one lived to be over 30!) and may remain together their entire adult lives if luck allows. Males and females each take significant part in raising the young, starting with building the nest. Working together, a pair will construct a nest near the top of a tree or on the edge of a cliff. Because they will continue to protect this territory, the nest may be used again in future years, if it can last that long.

Once the eggs are laid, female/male roles change. While the female incubates (sits on the eggs) for about 30 days, she will leave the nest only occasionally, while the male takes it upon himself to hunt for her. When the chicks hatch, the female will join the male in hunting, and both parents will provide food for the young. At 45 days old, the fledglings will start exploring away from the nest, but will stay close enough to be cared for by mom and dad for another month. Some individuals may stay with their parents for nearly double that time.

Red-tailed Hawks that breed in Massachusetts are year-round residents, but in the winter we also may see the individuals that breed in Canada and Maine as they fly south where winters are less severe. These individuals are partial migrants, who don’t need to go too far to weather the seasonal change. The ones that do migrate are able to do so efficiently by using thermals, or warm columns of air that are pushing upward, to keep them afloat as they soar. Flying from one thermal to another, many hawk species can travel great distances, expending very little energy.

What can you do for Red-tailed Hawks? If you’re looking to attract hawks to your yard, there are a few things you can do. Looking to deter hawks? We’ll cover that too.

- Supply tall perches or nesting platforms. You can leave tall trees on your property intact, and keep an eye on any nearby telephone poles, which hawks often use. If you want to build a perch, just make sure it’s at least 14 feet off the ground.

- Supply water in a tub or fountain that hawks and other birds can use. For safety you shouldn’t let the water become stagnant, so change it daily if you aren’t using a fountain to keep water circulated.

- Don’t use toxic forms of pest management. If hawks visit your property they will consume many pest species that include rodents. Toxic chemicals can be passed from prey to predator, or pesky rodent to handsome hawk in this case, so it’s important to say no to pesticides, and let nature do its job so you don’t have to!

Tips for deterring hawks:

- For people with animals at risk (such as chickens or rabbits), we recommend using top netting to deter hawks, not to mention a range of other potentially harmful species.

- Get a rooster! Roosters are hardwired to protect their hens. They are tough birds that will take on a hawk, but that doesn’t guarantee they’ll always win, just that they’ll always try.

A note on hawks at feeders: successful bird feeders are bound to attract the eye of hawks. Red-tailed Hawks might not be the most common bird of prey to visit a feeder, but it’s possible. This is the circle of life, and we can’t hold the hawk accountable for trying to survive. Remember – if you see that hawk, let it be. If it sticks around it will act as a pest control. Rats, squirrels, chipmunks, and yes – birds and rabbits – are all on the menu.

Red-tailed Hawk displaying its namesake – Lisa Hutchings

Perched Red-tailed Hawk with rusty red tail – Lisa Hutchings

Learning Tools From Mass Audubon

Read more about the Red-tailed Hawk breeding habits on our Breeding Bird Atlas page.

Consider the change in Red-tailed Hawk populations in Massachusetts.

Compare with other Massachusetts hawk species on our Bird of Prey page.

Looking for More Resources and Activities?

Observe Red-tailed Hawks through this live stream.

Watch this video on a juvenile Red-tailed Hawk learning to hunt.

Watch and learn from this video depicting the journey of three young Red-tailed Hawks to adulthood.

Read this iNaturalist’s Notebook story about young Red-tailed Hawks. Great for kids!

Get the facts and test your knowledge of Red-tailed Hawks.

Browse 15 other resources great for students K-12.

Create a hovering hawk craft and enjoy a great story told by a Red-tailed Hawk.

Draw a Red-tailed Hawk with these online instructions.

Color a photo of a Red-tailed Hawk.

Submissions

Red-tailed Hawk in Marblehead, MA – Facebook User

Juvenile Red-tailed Hawk – Facebook User

What’s Next

What would you like to learn about from your backyard? Let us know in the comments.

Stay tuned for the next Critter Card coming out on Monday, by email and Facebook.

Contact Us

Would you like to be added to Lisa Hutchings’ VIP email list? Receive special resources such as nature slideshows and educational tools for at-home learning. Send an email to [email protected] requesting to be added to the VIP list.