The annual cold-stun sea turtle stranding season on Cape Cod has two phases. The first phase is late fall when volunteers and staff patrol beaches and rush turtles to the New England Aquarium for life-saving treatment. But after turtles stop washing ashore, we move into phase two when the effort to help turtles takes a scientific turn.

Sanctuary director Bob Prescott gives instructions before a session at a necropsy lab at WHOI’s Quissett Campus (photo by Krill Carson)

Each week during January and February, Wellfleet Bay conducts necropsies (autopsies) on the turtles that did not survive hypothermia in the fall. These sessions are held at a state-of-the-art necropsy lab at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. There, an assortment of sanctuary staff, experienced volunteers, and researchers gathers to take advantage of a significant research opportunity.

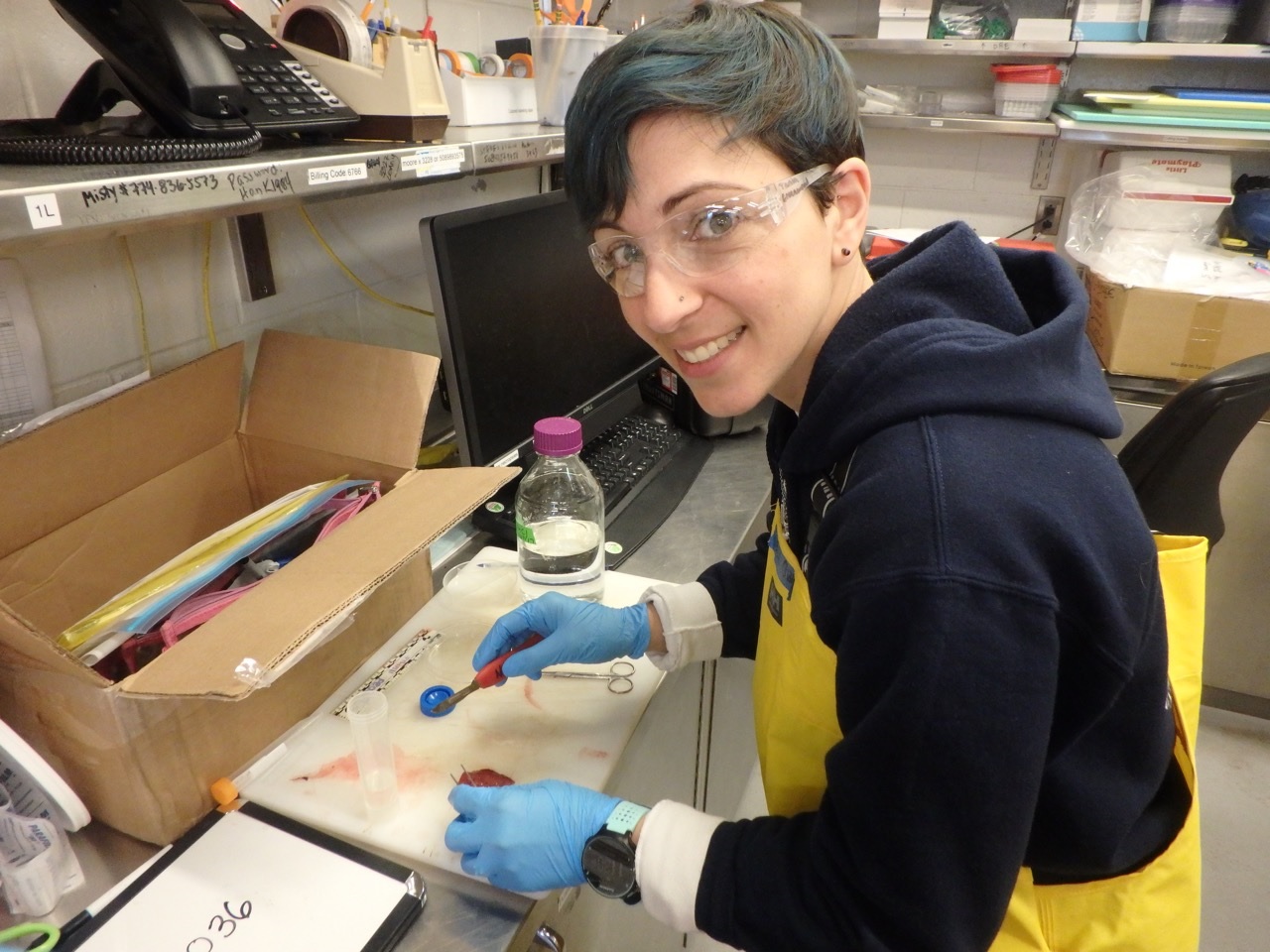

Each necropsy session begins with clean sharp tools and plastic bags for tissue samples.

The necropsies support a number of ongoing and future research projects. For instance, the front flippers from Kemp’s ridleys and loggerheads are collected for a study of turtle growth through the examination of growth rings on bones. There’s still much to be learned about aging turtles and the rate at which they develop. This information is important in population modeling used to forecast the overall health of a turtle population and to determine best management practices to rebuild its numbers.

Scientist Maureen Conte (on left) watches her colleague Heather Haas attach plastic bags to turtles for the collection of front flippers to be used in research that could help age turtles more accurately. Rear flippers are also used to train fisheries observers how to safely attach tags to live turtles accidentally caught at sea.

Some people are very interested in parasites. Carol “Krill” Carson, a long-time necropsy participant and founder of the New England Coastal Wildlife Alliance, has been carefully collecting parasites discovered in the turtles necropsied at Woods Hole. This year, Krill’s working with a PhD student at the University of Southern Mississippi who’s studying parasites and comparing those found here to parasites in other parts of the world.

Bridgewater State University student Tania Greenwood isolates a parasite from tissue to send samples to a PhD student at the University of Southern Mississippi. (photo by Krill Carson)

Another example of how our sea turtle work supports research is the shipment of thirty Kemp’s ridley carcasses to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration facility in Mississippi for a study of the rate of turtle decomposition in the Gulf of Mexico as well as drift patterns. This research is part of ongoing studies to understand how long turtles have been dead, where in the Gulf they may have died, and possibly how. Five additional ridley carcasses are also going to another NOAA facility in Galveston, Texas for experiments related to methods for determining the sex of a live immature turtle. Right now, sexing a live juvenile sea turtle can only be done through a minor invasive surgical procedure.

At the moment, the only simple way to confirm the sex of an immature sea turtle, such as this female loggerhead, is during a necropsy. Just above the ruler are the turtle’s ovaries (the white spots are follicles which contain immature eggs). Photo by Karen Strauss.

Over the course of the past four weeks, the necropsy team has had success sexing juvenile loggerheads based on how far an animal’s tail extends past its top shell or carapace. These measurements have been recorded and will continue to be gathered next year in an effort to determine the reliability of this method.

Understanding a sea turtle’s diet can shed light on more than just what it likes to eat. Researchers at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole are collecting tissue samples to look at stable isotope and fatty acid signatures in cold stunned Kemp’s ridleys, loggerheads and green sea turtles. These signatures–or “fingerprints”– can be used to identify not only what young turtles have been eating but whether and how diets vary by species, age and overall condition. The research may also reveal something about the pollutants turtles are exposed to. Stable isotope analysis could also be used to determine where turtles have been eating, providing insight into their travels.

Volunteer Sandy McKean labels a sample vial. Samples from turtles are regularly provided to NOAA’s Marine Turtle Research Program at LaJolla, California, a worldwide central depository for sea turtle tissue and DNA samples.

Although turtle strandings in the fall have been an annual event on Cape Cod for more than 30 years, the fact is juvenile Kemp’s ridley, green and loggerhead sea turtles are just not seen very often. Making the most of the animals we recover, even the turtles that don’t survive, is a way we hope to assist scientists working to learn more about and, ultimately, to protect these remarkable creatures.

Thanks to Wellfleet Bay sea turtle researcher Karen Dourdeville for her help with this post.