The fall bird banding season starts in September with lots of noisy catbirds flying into the mist nets and feisty chickadees—the vast majority born just this year. Adult chickadees come later, apparently lying low until they complete their full feather molts.

Come early-to-mid-October, the birds we find in the nets seem to change, if not overnight, then certainly in a matter of days.

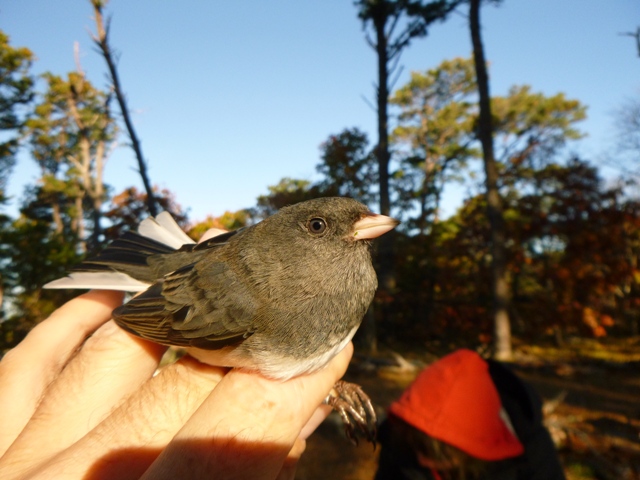

You know it’s truly fall when these guys start showing up.

Dark-eyed Juncos (aka “snow birds”) breed in Canada and some spend winter in relatively balmy Massachusetts (photo by Dan Lipp)

Early October was the heart of the batting order for warblers. This Mourning Warbler, a female hatched this year, was a first for our banding station. These birds tend to travel in the middle of the warbler pack in fall.

photo by Elora Grahame

Then, there are the late season travelers. This lovely pair of Black-throated Blue Warblers was caught on the same day, giving us an opportunity to photograph the two very different looking sexes.

These birds are a perfect example of why identifying warblers can be so exasperating (photo by James Junda)

There were a couple of days when wrens were clearly on the move. We caught our first Winter Wren, along with a Marsh Wren on the same morning.

Seeing birds at such close range also provides an opportunity to appreciate how each species of bird is adapted to its habitat. Compare the difference in size between the eyes of the Marsh Wren and the Winter Wren.

The eyes of the Marsh Wren, at left, are smaller than those of the Winter Wren, at right (photo by Elora Grahame)

The relatively larger eyes of the Winter Wren reflect its preference for a low light, forest canopy habitat. The Marsh Wren, which lives in the brighter world of open wetlands, has smaller eyes.

One day recently we had the chance to look at two species of thrushes at close range.

Bander James Junda compares a Hermit Thrush on the left and a Swainson’s Thrush on the right (photo by Elora Grahame)

Both birds seem very similar given their overall color and brown speckled breasts. But the Hermit Thrush (left) is a little chunkier in shape and has a reddish cast to its tail. The Swainson’s has “spectacles” around the eyes, is more slender, and has longer flight feathers, which reflects this bird’s much farther fall migration to Central and South America.

Having the chance to hold a wild bird is definitely exciting . But for anyone trying to sharpen their bird ID skills, being able to compare birds side by side and note their differences is a special opportunity.