Sea turtle staffer Maureen Duffy prepares to conduct a necropsy on a dead leatherback, not usually seen in the winter. As part of NOAA’s sea turtle stranding and salvage network, Wellfleet Bay staff responds to sea turtle strandings year round and collects data on every turtle. (Photo courtesy of Esther Horvath).

The cold-stunned sea turtle rescue season rarely ends with the same zeal it started with. By the end of December, the vast majority of turtles found, especially the smaller Kemp’s ridleys, are dead.

But as many of our volunteers have discovered, the job of retrieving dead turtles is still very important, especially to scientists working to learn more about sea turtles.

The hundreds of turtles that come in, half of which may not survive hypothermia, contribute substantially to the growing body of knowledge about these endangered and threatened marine animals. Every year, Wellfleet Bay receives requests for turtle carcasses and/or tissue samples to aid new and ongoing research.

One study by a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration team in Mississippi is focused on the length of time it takes a dead Kemp’s ridley to decompose. Dead turtles typically build up gasses that cause them to float and eventually strand. The study’s aim is to understand the differences in this timing in cold water versus warm. In the team’s words: “ Knowledge of this time to bloat and float at cold temperatures is critical to backtrack modeling of carcasses and determining the likely mortality source involved in causing the strandings.” Wellfleet Bay sent twenty-six cold-stunned Kemp’s ridley carcasses by overnight mail to Mississippi for this ongoing research.

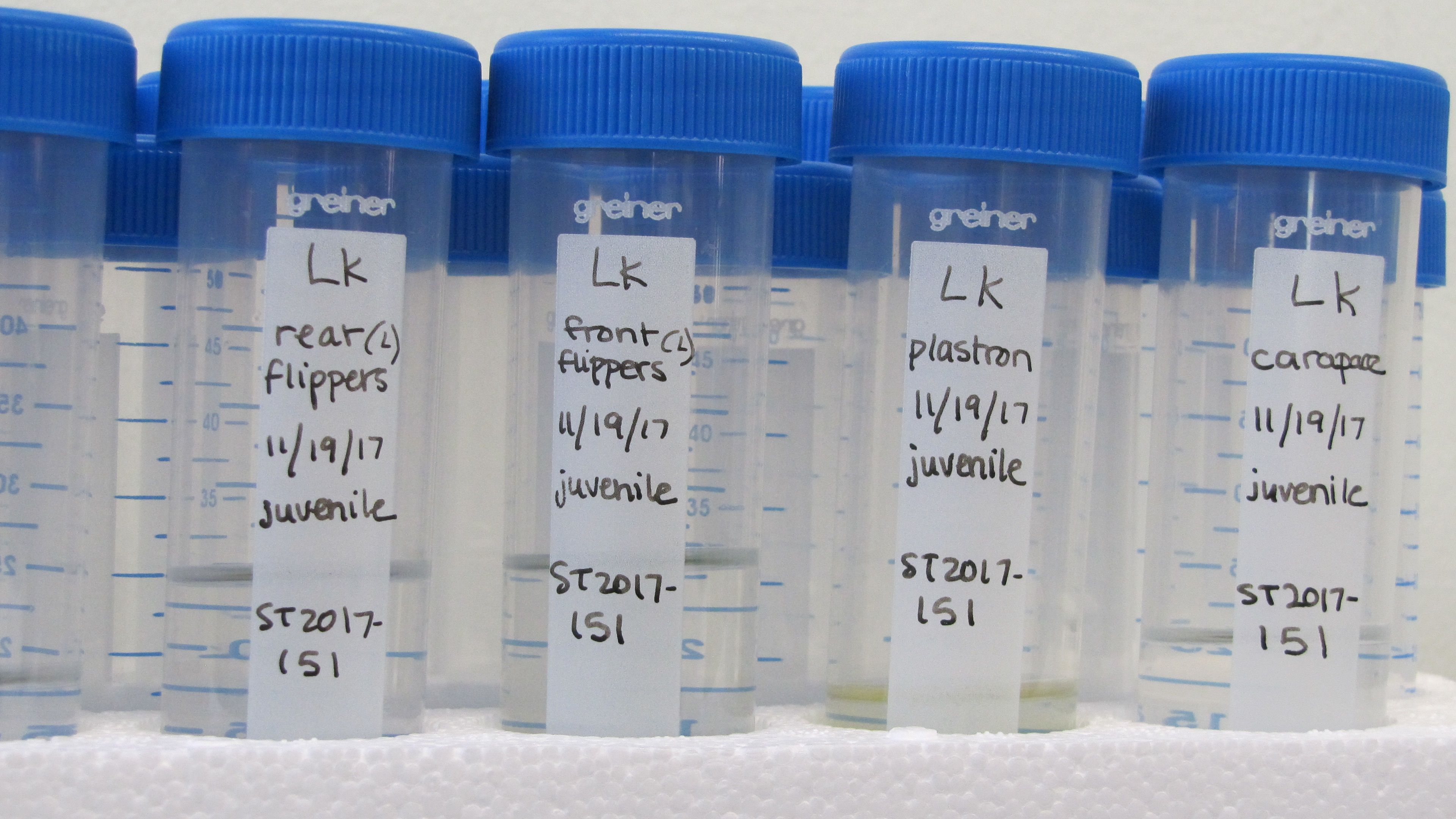

These vials contain tissue samples for microscopic analysis of diatoms from turtles that did not survive cold-stunning.

This fall, our sea turtle staff began collecting tissue samples as part of a pilot study with researcher Roksana Majewska, currently a research fellow at North-West University in South Africa, who studies diatoms. Diatoms are single cell marine plants (algae) which have a shell wall made of silica. They’ve been found to be part of the “epibiont community” (organisms that attach to and live on the surface of other organisms) on several sea turtle species examined so far, with at least two new species of diatoms discovered.

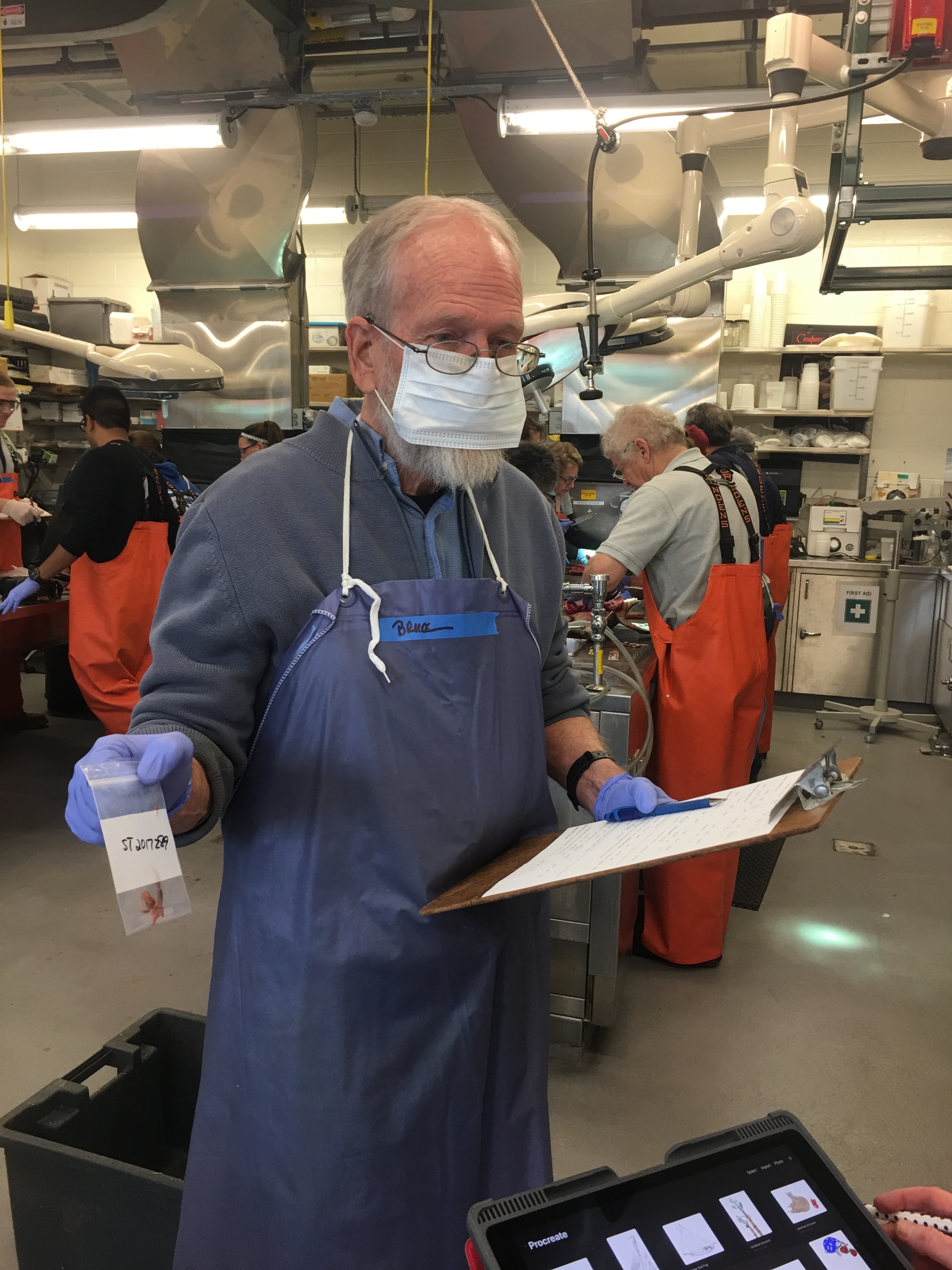

Bruce Hurter holds a bag containing the remains of a crab taken from the stomach of a Kemp’s ridley during a necropsy. (Photo by Krill Carson, NECWA).

Roksana’s study provides the first look at possible diatoms on juvenile Kemp’s ridleys. She says diatoms could shed light on the life history of the sea turtles, including their diet, feeding locations, and migration routes and times.

While there are other studies we are contributing to as well, we’ve also been building an important database over the 20 years that we’ve conducted sea turtle necropsies, including key fat measurements, sex ratio, gastro-intestinal tract contents, and organ and body condition—fundamental information that already is proving valuable to sea turtle research.

At the first Wellfleet Bay necropsy of the year at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, two noteworthy finds included a fairly large piece of black balloon in the stomach of a ridley as well as–of all things–lady bugs!

Remains of lady bugs removed from the intestine of a Kemp’s ridley turtle. (Photo by Karen Strauss)

Our mantra of “No turtle left behind” is certainly about saving every live turtle we possibly can. But it also applies to our commitment to make sure we make the most of every opportunity to learn about and help conserve these animals.

This blog post was contributed by Wellfleet Bay sea turtle research associate, Karen Dourdeville.

Always great to hear about WBWS’s ongoing turtle rescue program!! Found the ladybugs to be interesting!