Thanks to the tireless efforts of Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary research staff and dedicated volunteers, hundreds of diamondback terrapin nests are protected in the towns of Wellfleet, Eastham and Orleans each year, resulting in thousands of hatchlings released back into the marsh. This is extremely important work, as diamondback terrapins are listed as Threatened under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

Nine diamondback terrapins basking on a log in the sanctuary salt marsh (photo by Jeannette Bragger)

Despite all these efforts, we still do not fully understand the health of the population in Wellfleet Bay and there are many questions we still want to answer: What is the population size? What is the age structure? Are we finding mostly old adults? Or are the younger generations surviving? What is the ratio between males and females? Answering these questions will give us insight into the health of the population.

This year, in collaboration with Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program and the University of Massachusetts Amherst, we’ve started exciting research to try to answer our first question: What is the population size of diamondback terrapins in Wellfleet Bay? Unfortunately, it is impossible to capture every terrapin in Wellfleet Bay, so how do achieve a confident population estimate?

First, we design a standardized protocol to capture a sample of the population. This is achieved by collecting the same data, in the same way, during every capture survey. Standardizing how we capture these turtles eliminates bias (influencing results to favor an outcome) and will be a baseline for long term monitoring. We will be using a widely used method for species population monitoring called Mark-Recapture. This involves capturing turtles, marking each individual then releasing them back where they were captured. This procedure is repeated throughout the season. The ratio of marked to unmarked individuals is statistically analyzed and provides an estimate of the population size.

Turtle gardens are cleared areas near salt marshes that provide good nesting habitat.

This research will take a couple years to perfect the survey protocol needed to achieve reliable population estimates. This protocol can then be used year after year to collect more data and achieve more refined estimates. It will serve as a means of monitoring our population and making informed conservation decisions based on population trends over time.

For instance, if ten years down the road research reveals a significant loss of mature adult females as a result of increased road mortality, conservation efforts could focus on creating additional nesting gardens in locations away from roads, installing fencing along road crossing hot spots, or updating road infrastructure to include turtle passage tunnels.

Two Mark-Recapture survey locations in Wellfleet Bay: Chipman’s Cove (top) and The Run (Bottom)

The two sites chosen to conduct Mark-Recapture surveys are Chipman’s Cove near Indian Neck and The Run at the sanctuary. These two sites were chosen because they are known for large (seasonal) concentrations of turtles and are easily accessible. We survey both sites following their assigned survey protocol and capture terrapins via a dip net or by hand.

Once the survey is finished, we process each turtle taking carapace and plastron measurements, weight, age and sex. We also check for any injuries or anomalies on their shells, record that information and take photos. Lastly, we inject each turtle captured with a PIT (Passive Integrated Transponder) tag just under the skin in their rear left thigh.

PIT tags are a widely used microchip containing a unique number that identifies each turtle. These same tags are also used at the vet to microchip your dogs and cats!

They are minimally invasive and will last the life of the turtle. A hand-held PIT tag scanner is used to scan turtles for these tags. If a turtle has a PIT tag, the scanner will beep and that turtle’s unique number will appear of the screen. Once every turtle is processed, they are released back in the general location they were found.

PIT Tag (Passive Integrated Transponder) on left; tag reader displaying a turtle’s new ID number (right).

The survey protocols for this population study are still in the design and testing phase, however so far this year we have conducted 66 surveys and have captured and marked 188 terrapins! The surveys will continue through early October and resume next spring.

LITs participating in processing of the terrapins.

This research is not only exciting for the research staff here at the sanctuary but also for our younger generations of hopeful biologists.

This year a group of 8 LITs (Leaders in Training) from our day camp had the opportunity to come out with us on a survey in “The Run” located right off the sanctuary’s tidal flats. They were grouped with an experienced research staff member and conducted the survey with us–from searching the waters and capturing terrapins to processing and release.

The eight LITs who participated in the survey. One last goodbye before the release!

These teenagers were not only able to learn about our research, but participate fully in the process. I’m looking forward to next summer and more opportunities to get kids excited about science. The study and conservation of our diamondback terrapin population in Wellfleet Bay will need to continue long after me and the current research staff. We must do our part to inspire and guide younger generations to pursue careers in conservation.

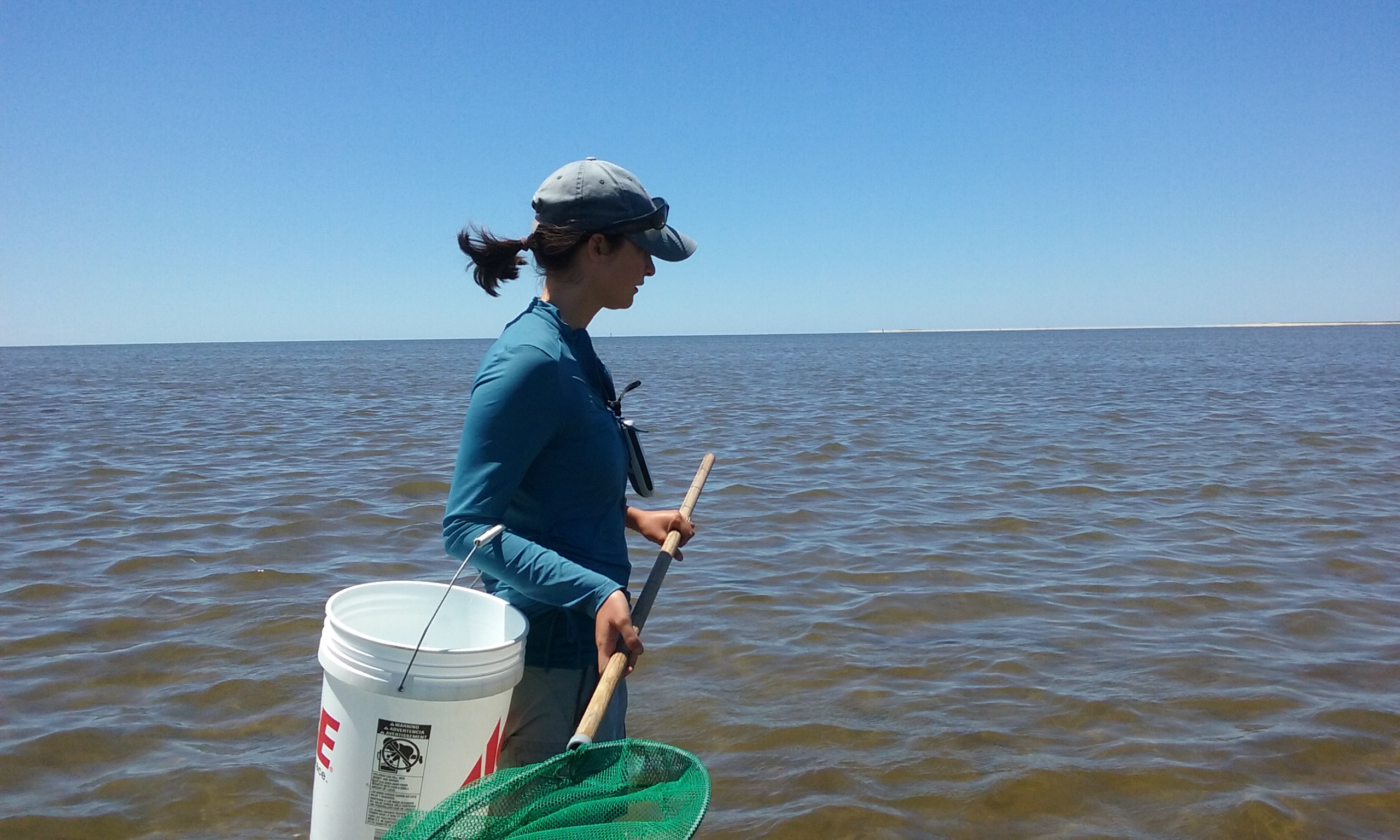

UMass-Amherst master’s student Patricia Levasseur conducting a survey.

This post was contributed by Patricia Levasseur, a graduate student at UMass-Amherst pursuing a Masters of Science degree in Wildlife Conservation Biology. Patty has ten years of field research experience ranging from headwater stream amphibians in Oregon to brown tree snakes on the island of Guam to Piping Plovers, Blanding’s turtles, red-bellied cooters, wood turtles, blue-spotted salamanders and diamondback terrapins. She lives in Acushnet, Massachusetts with her husband, 2 dogs and 8 chickens.