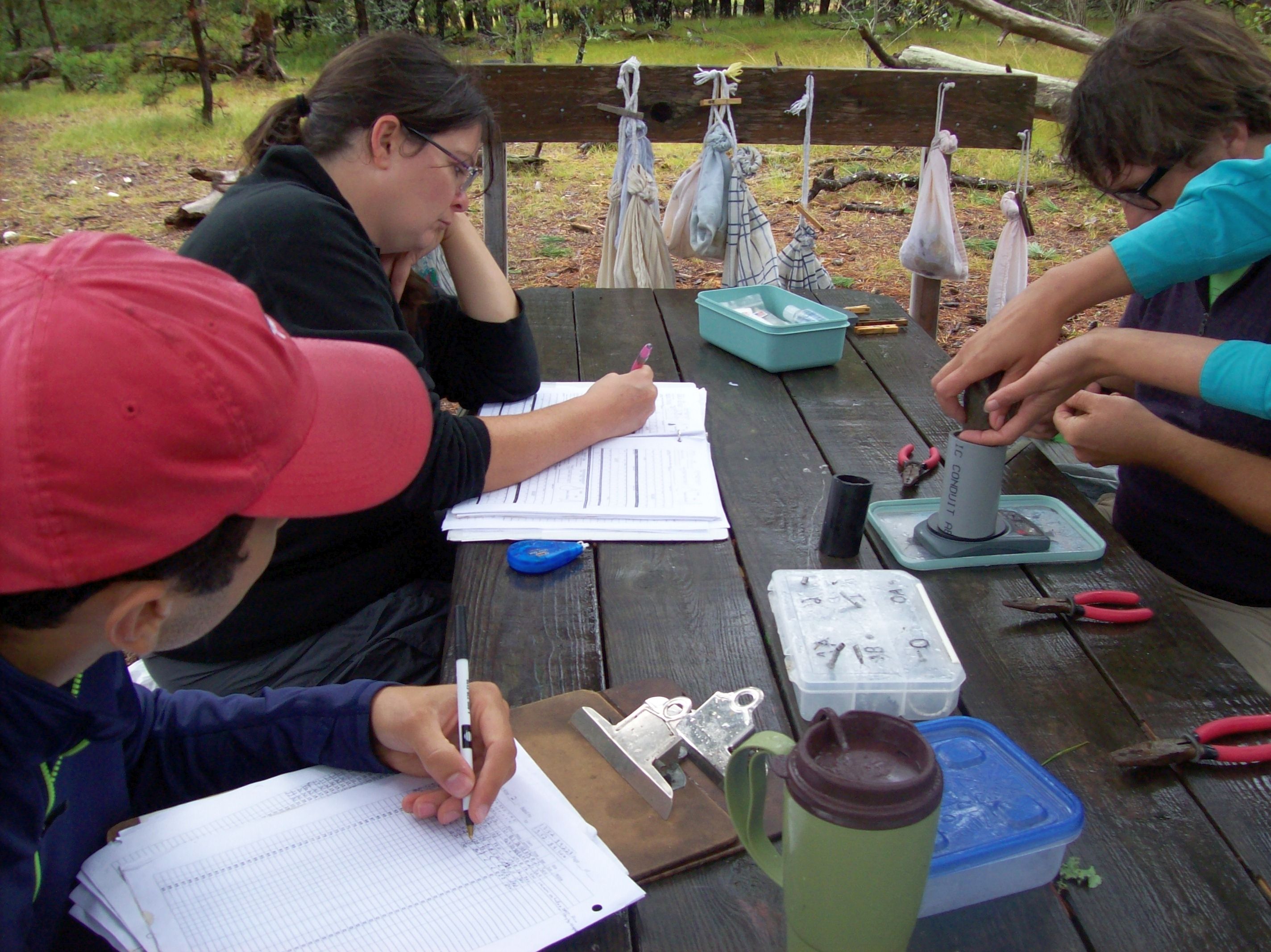

There is a rich history of bird banding at Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary that stretches back long before the opening of our present station in fall 2014.

The earliest known records are those of the Austin Ornithological Research Station, established by Dr. Oliver L. Austin Sr. and Jr. in 1929. The Austins and their intrepid crew banded just about any kind of bird they could get their hands on, songbirds included, for more than a quarter century—a considerable amount of time to continue monitoring the bird population in a single location. They were also among the first in the US to use Japanese mist nets, the same fine mesh, badminton-like nets used today.

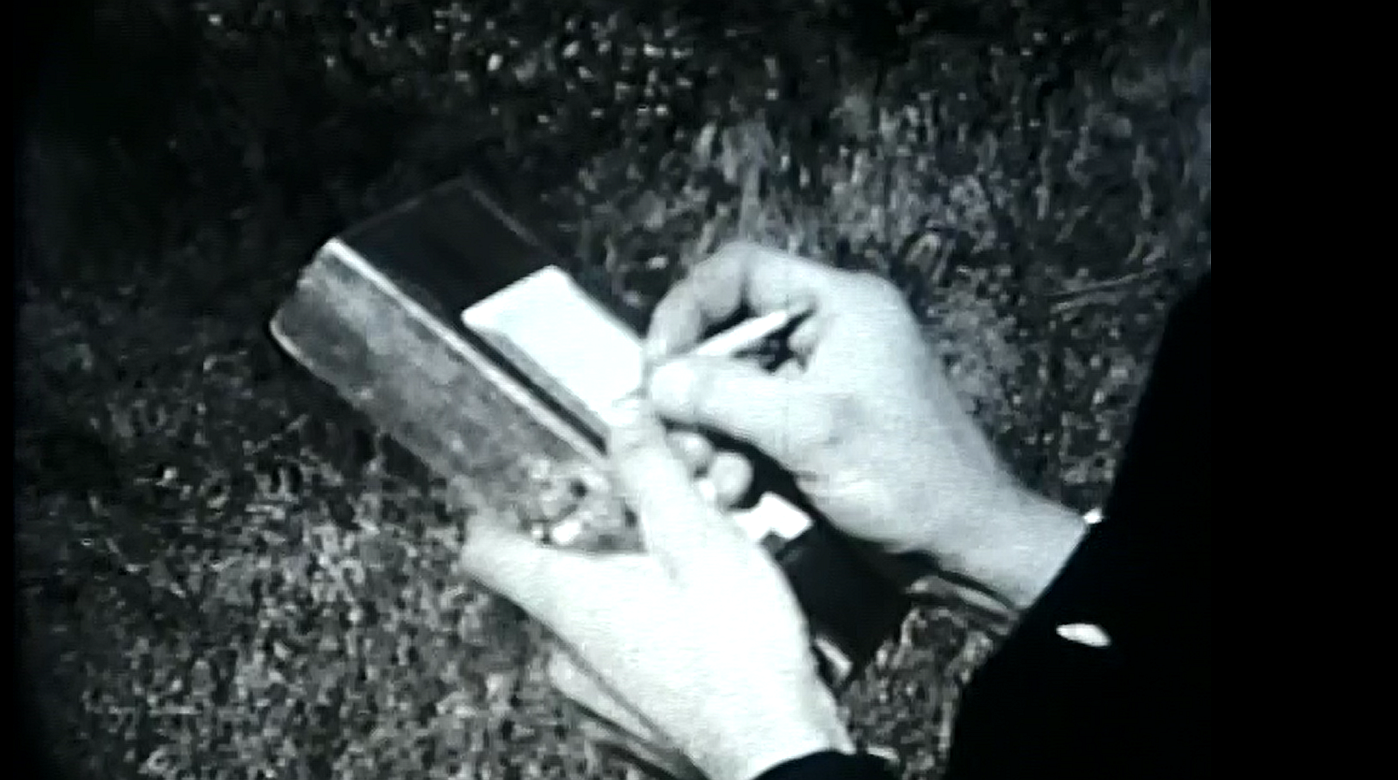

Both a journal entry and an old film reel from which this photo is taken indicate that as early as September 20, 1930, the Austins used, among other traps, nets similar in design to the mist nets operated by contemporary banders. A White-throated Sparrow is extracted from a net in the 1930 footage, above.

Given how much the landscape of Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary has changed since 1929, it would be most intriguing to compare the bird species inhabiting today’s sanctuary to those frequenting the same property over eighty years ago. So, what ever happened to the old data?

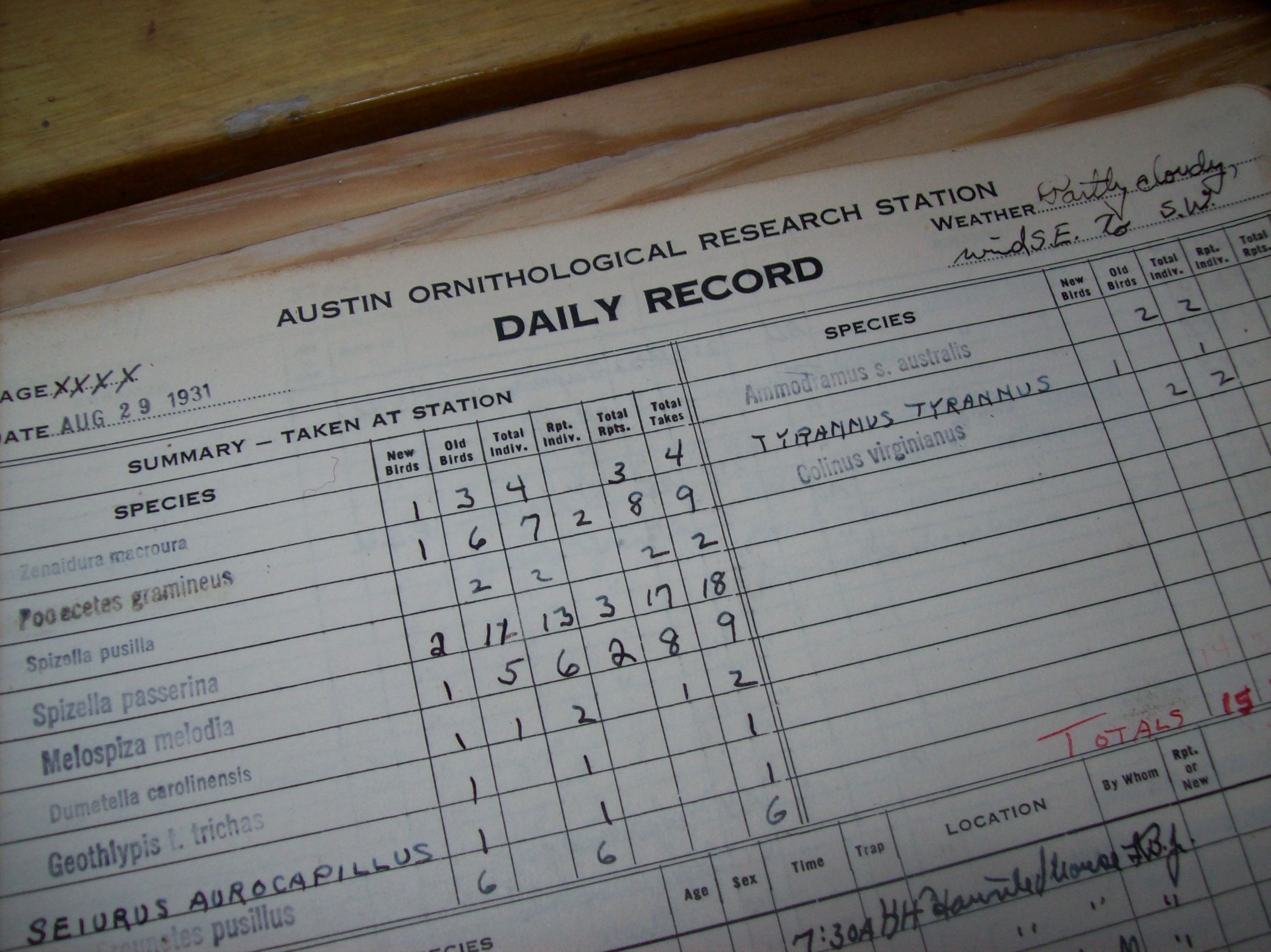

Typical page in Austin banding data collection.

The Austin data exists in an attic bookshelf packed with volumes upon volumes of banding history, quite difficult to analyze in its present state. As a bird bander myself, I couldn’t help but feel drawn to these neglected archives, and so began my endeavor to digitize the old records.

All analog! Unidentified bird bander makes notes.

This is no easy feat. The earliest of these records are handwritten in what is sometimes an illegible scrawl. The birds’ names given are in scientific notation, and many of the Latin names have changed since 1930. Between regular misspellings and outdated nomenclature, it often takes more detective work than a Google search to figure out exactly what bird species had been banded.

After entering data ranging from 1930-1931, I noticed a changing dynamic in our regular avian residents over time. Both Vesper and Grasshopper Sparrows were caught regularly back then, but neither species has been captured on the property since fall 2014. Most of the residual open farmland that covered outer Cape Cod in the early 1930’s has since grown up into forest, dramatically decreasing suitable breeding habitat for these grassland sparrows.

Wellfleet Bay is no longer on the radar of Vesper Sparrows.

Some of our most usual suspects today make no appearances in the early Austin records. Tufted Titmice and Northern Cardinals are notably absent from the 1930-1931 banding data, but they are regular captures today. Similarly, a 1930 journal entry describes the Austins’ first sighting of a Red-bellied Woodpecker on the property, then a rare southern visitor. Today, they are common in forested areas of the Cape and are often attracted to suet feeders.

A Red-bellied Woodpecker was big news at the Austin Ornithological Research Station in 1930. They’re a lot more common now but still very nice to see. (photo by Elora Grahame).

The volumes of data from the Austin Ornithological Research Station range from 1930 to 1958, and digitizing all of the data is an enormous undertaking that will likely take several years and additional support to complete. Despite the project’s challenges, realizing this goal will provide unprecedented insight into the changing dynamics of the sanctuary’s bird communities over a near century.

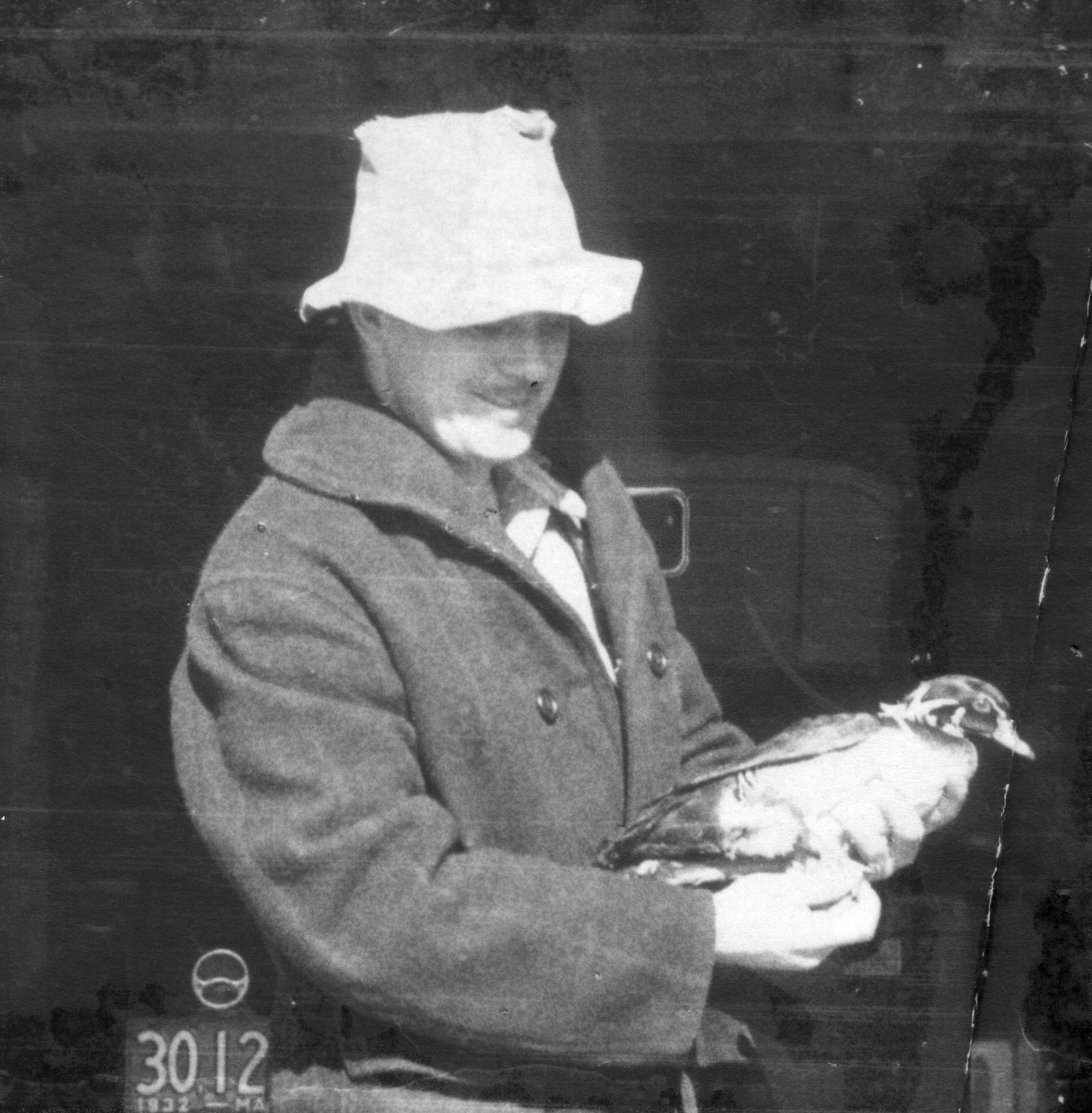

Oliver Austin, Jr and a Wood Duck, a less common species at the sanctuary in recent years.

Elora Grahame started her banding career in 2012 with Northern Saw-whet Owls, then songbirds in 2013, and has worked as an assistant bander with master bander James Junda at Wellfleet Bay through spring and fall of 2016. After fall migration,Elora changed gears and joined the sanctuary’s sea turtle rescue team.