Every night between November and March, a steady trickle of American Crows pours through the skies of Lawrence and Andover, MA. The trickle quickly becomes a stream. Soon, a deluge. Crows spread from horizon to horizon as they fly together to their communal roost. The number of crows varies every year, but there can be as many of 12,000 or 15,000 at a time.

The word “Hitchcockian” does not accurately describe every mass gathering of birds, though the term is used broadly. Murmurations of European Starlings dance and contort themselves in the sky, recalling a moving sculpture. Staging flocks of migratory Tree Swallows are clamorous and chaotic, but the birds move with a light and airy agility that lends a whimsical feel to the spectacle. American Crows, on the other hand, flow by steadily in a single direction. Their pace is deliberate, and their rowing wingbeats inexorable. Uniformly black, crows appear at dusk as large, dark shadows against the sky. They even sometimes approach people out of curiosity and stare at us with an unreadable avian gaze. These are the birds that inspired Hitchcock’s eponymous movie, playing off humans’ unease. In reality, though, members of the crow family are harmless, cooperative, and even empathetic. And while some causal observers might find a crow roost uncanny, birdwatchers and nature-lovers often find in them a source of wonder and beauty.

Why Roost in Numbers?

As some of the world’s most intelligent birds, what could American Crows be up to at these roosts? Traditional theories dictate that crows roost together for safety or warmth, or use communal roosts to be able to select mates from a larger pool of candidates. But hungry crows also follow better-fed birds from the roost in the morning, suggesting they are seeking out productive feeding sites, and that roosts can facilitate cooperation. Some roosts are furthermore located strategically near feeding sites, such that crows can grab a reliable snack when they leave for the day and when they return at night.

Thousands of crows gathering together in the same place every night make easy pickings for predators like Great Horned Owls. As a result, American Crows gather at a secondary location, or “staging area,” before continuing on to their real roost after nightfall. American Crows will further confuse predators by changing the location of the staging area, or even the roost itself, every few nights. Some human observers confuse these staging areas for the actual roost, not knowing the roost is several hundred feet to several miles away— unless they stay after dark to watch the crows move a second time.

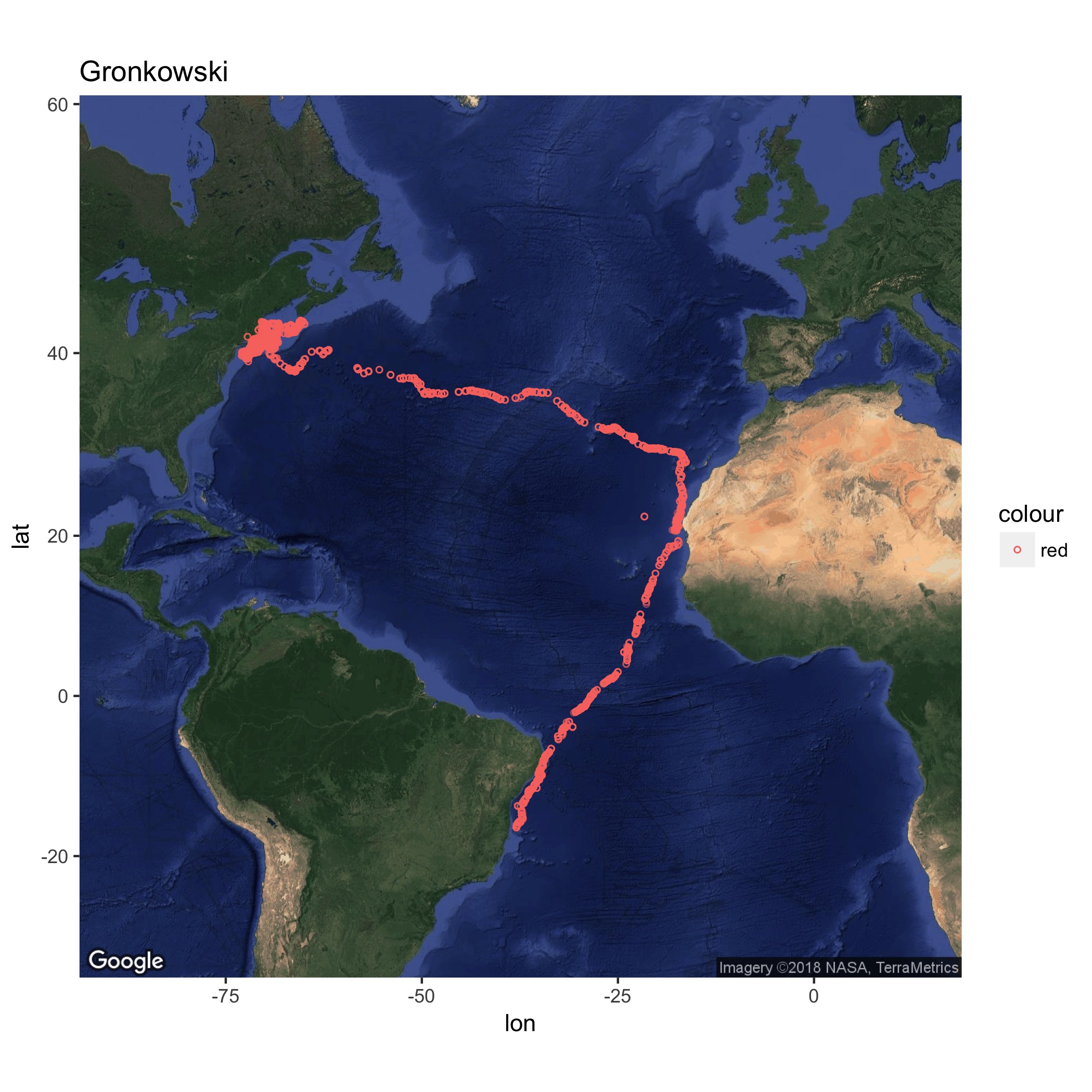

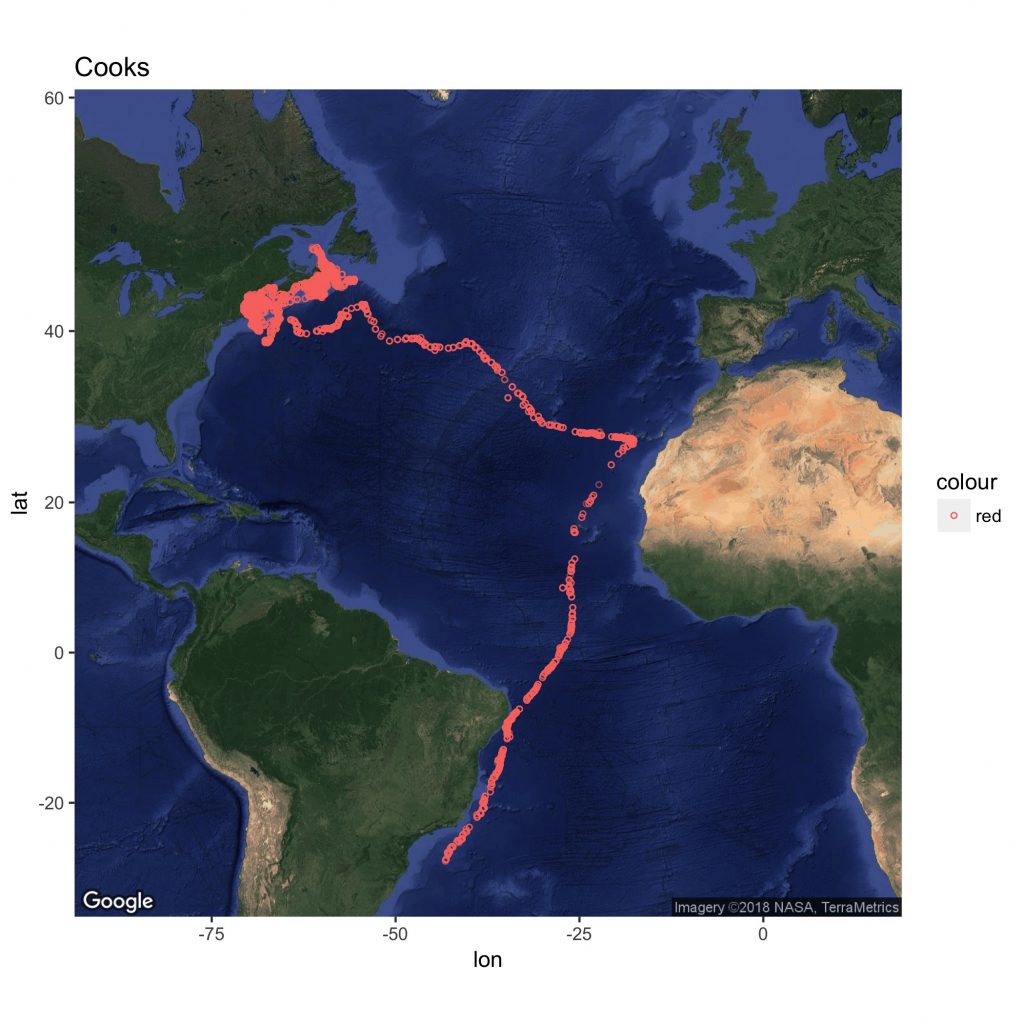

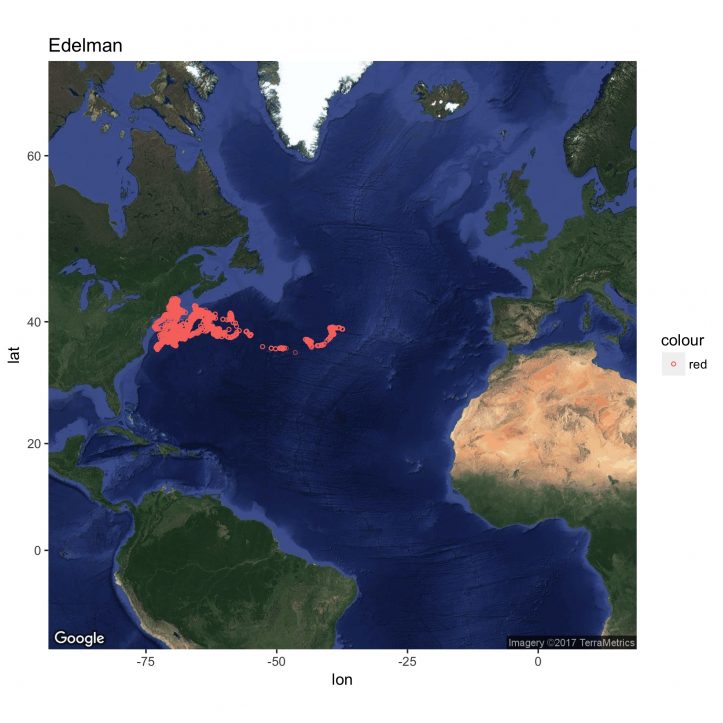

The American Crows in Lawrence are surprisingly wide-ranging when not at their roost. Pellets they cough up have revealed saltmarsh snails, telling us that they forage at least as far away as the New England coast. Some of the birds are seasonally migratory, and spend the breeding season far to the north on the St. John’s River in Canada.

Viewing The Mass Roost

To find the crow roost in Lawrence, park in the lot for the New Balance factory on the east side of South Union Street. Cross the street and slowly, quietly, walk partway over the bridge on the Merrimack River. The crows should be in the trees on the north side, numbering into the thousands. Check out the surrounding area for the crows’ staging grounds as well- they have a particular affinity for the parking lots in the industrial park between South Canal Street/Andover Street and the river, as well as Island Street and Pemberton Park.

Some of these birds will be returning to their breeding ground soon, with the rest pairing off and dispersing throughout the state- shutting down the roost until November. Try to catch the spectacle while you still can, or make a plan to check it out next winter.