A Magnolia Warbler perches in a shrub. Photo by William Freedberg

A late-June morning at the Quabbin Reservoir: Winter Wren songs echo from hollows and wetland thickets. Blackburnian Warblers whisper their buzzy, quiet notes from the canopy. Blue-headed Vireos squeak and argue over perches in spruce trees. These birds, like many species that prefer conifers or highland forests, are rarely seen outside of migration in eastern Massachusetts. At the Quabbin, it’s hard to miss them.

In the background there’s a constant clamor from the Quabbin’s most vocal and abundant woodland breeders: Red-eyed Vireos, Veeries, Ovenbirds, and Scarlet Tanagers.

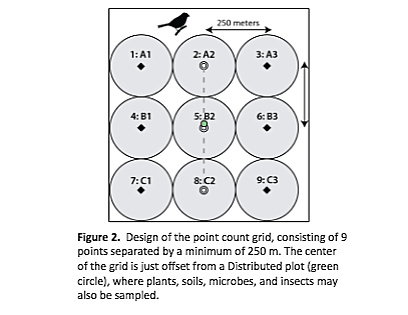

Amid the birdsong, there’s the faint scratching of my pencil and clipboard. Point 4, Minute 1 // Scarlet Tanager. Male. Calling. 19 meters // Ovenbird. Unknown sex. Singing. 33 meters. The birds are a thick during dawn chorus, and between recording each species, sex, behavior, and distance from me, it’s hard to keep up. The survey period passes quickly, and it’s time to hike to the next count site.

The data we collected that morning will eventually be used by the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON), an organization which studies large-scale environmental change at over 70 sites across the US, and which partners with Mass Audubon to collect bird data in New England. Normally, it takes just one person to run bird surveys—but recent security concerns at the Quabbin mean that all field technicians are now accompanied by a NEON escort to drive around restricted-access roads.

My field escort that day was Jamie, a soft-spoken botanist who had just moved to New England from Appalachia. When he mentioned he hoped to see his first moose in the Quabbin, I thought it was a farfetched idea, not knowing that around 100 moose make their year-round homes there. As if to prove a point, a cow moose stepped into the road later that day as we were on our way out.

A blurry, through-the-windshield photo of the moose that wouldn’t move.

We paused before inching the car towards the moose. The moose paused, too, and took several deliberate paces towards us. We noticed a smaller second pair of ears protruding from the roadside vegetation, and realized the moose was putting itself between us and its calf. That was our cue to put the car in reverse and give it some room; we would have to wait it out if we wanted to get to our destination safely.

Rolling down the windows, we were surprised to hear a singing Magnolia Warbler, a rare breeder for Central Massachusetts. The banana-yellow male flew across the road, giving us excellent looks at his black mask and bold stripes. I broke out a granola bar and Jamie unwrapped his lunch as we watched the moose feed and listened to the warblers. The mammoth ungulate in our way eventually ambled off, but we were in no rush to leave: life at the Quabbin was good.