Climate change is not only shifting the breeding season for northern forest birds, but it is also shortening it for some, according to a 43-year study co-authored by a UMass Amherst ecologist.

The study examined 73 species of boreal birds in Finland, but the results reflect patterns in bird observations from other parts of the world as well.

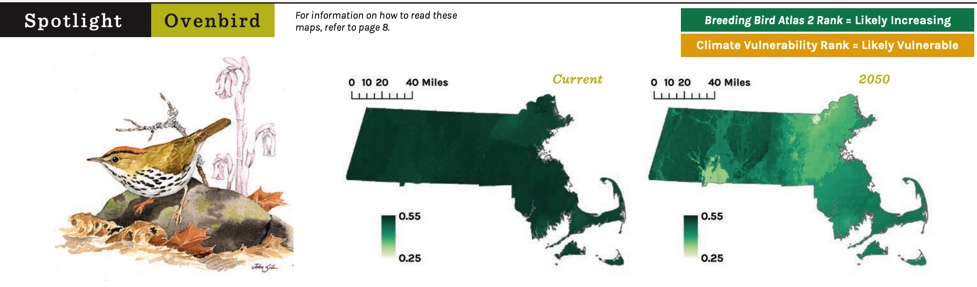

Ecologists have shown how climate change effects birds’ ranges, as well as the timing of some of the key phases in their lives. For background, many birds of the Northeastern US will experience range shifts (many of which are already underway) as global temperatures increase, according to models in Mass Audubon’s 2017 State of the Birds report. Climate change tends to affect birds’ ranges by moving their habitat or food supply further north or to higher elevations. While birds are somewhat temperature-sensitive, the plants and insects they rely on tend to respond much more sharply to changing conditions, bringing the birds with them.

Other long-term studies have shown that seasonal peaks in insect abundance no longer line up with the arrival of migratory birds that feed on them— and that other factors, like weather patterns, make it difficult for birds to change their schedules accordingly.

But the new 43-year study from Finland is the first to look at the duration of the breeding period from start to end. Around a third of species examined by researchers showed some shortening of their breeding period. Most of the study species started or ended breeding slightly earlier.

At first glance, a reader might worry about the third of birds that breed on an accelerated schedule, and assume that the other two-thirds of species were unaffected. Indeed, the study noted that shorter breeding periods increased competition among individuals of a species— for example, by synchronizing the times that adults were arriving or that chicks were hatching and leaving the nest.

But that’s only part of the problem. In fact, the species that showed no indication of changing their breeding schedule may be cause for greater conservation concern. Just because only some birds are adapting to a shorter “ideal” breeding period doesn’t mean that other birds aren’t feeling the squeeze; other species could be failing to adapt to changing conditions, even if they face the same challenges. The study’s authors pointed out that most of the birds with a curtailed breeding season are either short-distance migrants or year-round residents. Long-distance migrants— whose breeding schedule showed fewer changes— are less able to adjust their migration and breeding dates because of constraints at stopover sites or wintering areas.

Take a Climate Pledge

Climate change affects so much more than birds. Everything from pollinators that maintain food crops, to shellfish and ocean ecosystems, to the cities we live in are facing new climate-related threats.

We can help when we come together to act on climate! It’s easy to reduce your personal carbon footprint by taking one of our climate pledges to commit to greener transportation, sustainable eating habits, or easing pressure on the energy grid when demand is highest. While advocacy, activism, and systemic change are also key to stopping climate change, adjusting our consumption habits is an excellent first step to protect the planet we love.