It’s been an incredible past few weeks for rare birds in Massachusetts. First, a Purple Gallinule showed up in Milton. Then a White-faced Ibis arrived in Sterling, and a Tropical Kingbird shocked birders in Belmont—the first ever to be seen in Middlesex County. Finally, the first Pacific-Slope Flycatcher seen anywhere in the state was spotted in Hadley, and a Western Kingbird and Rufous Hummingbird rounded out the glut of unusual visitors.

It’s tempting to think that these out-of-range birds (or “vagrants”) are the result of climate change. Although climate change certainly affects species’ normal ranges, and may make vagrancy more common and extreme, it’s a reach to say that these “lost” birds themselves indicate any larger trends.

Instead, these birds are just as likely examples of species that only show in Massachusetts every several hundred years. This phenomenon of once-in-a-lifetime birds has plenty of precedent. Consider, for example, the first time a Masked Duck was seen in Massachusetts was in 1889—and the species hasn’t been reported in New England since. Similarly, the first and only record of a Brewer’s Sparrow was in 1873, and the first and only record of a White-tailed Kite was in 1910.

Vagrants: Unpredictable in Predictable Ways

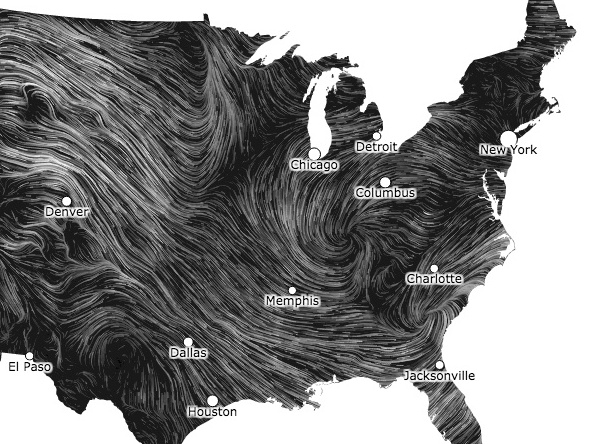

As fall migration draws to a close, there’s almost always a spike in vagrant birds in Massachusetts. Birds from the interior southwest of the US ride winds blowing northeast, often making it as far as the coast.

Many bird populations contain a few individuals prone to wandering. In some cases, wanderers are biologically hard-wired to migrate differently than others of their species, and in other cases, the cause is unknown. These outliers aren’t unique to migratory species; even flightless penguins have been documented walking into the icy mountains of Antarctica, far from any food source.

Most vagrants either perish or (less often) make it back to their home ranges. Even if the vast majority of these birds don’t manage to reproduce on terra incognita, some scientists theorize that having a few exploratory or mis-oriented individuals gives the species an evolutionary advantage. This may allow a population to very occasionally colonize new, faraway areas that turn out to be hospitable, serving as a bulwark against sudden cataclysmic change across its entire normal range.

Climate Affects Vagrants, But Vagrants Aren’t Necessarily Climate Indicators

Fall isn’t the only time when wind patterns regularly bring Massachusetts a handful of unusual birds. Southern birds that overshoot their breeding grounds in spring are mostly the result of wind patterns that blow them far over the Atlantic, where they continue north until making landfall in New England. Even more noticeable are the hurricanes that have brought tropical seabirds like Sooty Terns and Red-billed Tropicbirds inland into Massachusetts.

As rising global temperatures create stronger storms and shift continental wind currents, it’s reasonable to think that new patterns in bird vagrancy will emerge. This doesn’t mean, however, that recent “firsts” (such as last month’s Pacific-slope Flycatcher or Tropical Kingbird) are indicators of climate change– especially with only 200 years of records and a long list of vagrants that showed up in the 18th century and never again.

Demonstrating an increase in vagrant birds (or changes in where they show up) is a tricky proposition, in part because there’s no good way to adjust for how many people are looking. Not only has the number of birders increased dramatically since the 19th century, but birders’ knowledge of how to predict vagrants has improved—and their interest in finding them has intensified. This complicates studying patterns in bird vagrancy, let alone linking them to long-term climate trends.