Leaving the lush life at Tufts for the wilds of Wellfleet Bay (Photo by Karen Strauss)

Five small noses tested the air—the unfamiliar scents of salt, mud, wrack and pine trees on a damp, overcast May day on Wellfleet’s Lieutenant Island. Though creatures of the salt marsh, these diamondback terrapin hatchlings were meeting the marsh for the first time. Unlike other hatchlings of their kind that emerged from their eggs beneath the sand and struggled to the surface of their nests, these turtles had taken a different path to get to Lieutenant Island.

This northern diamondback terrapin, a threatened species in Massachusetts, was hit by a car on Lt. Island last year. Happily, she was successfully treated and rehabbed and her eggs protected and incubated at Tufts. (Photo by Karen Strauss)

On June 29, 2016, a car hit their mother as she was walking along Lt. Island Road looking for a good place to nest. With the help of local residents, my terrapin team and Wellfleet Bay staff and volunteers, she was rescued and treated at Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine and released at Lt. Island last September. The staff at Tufts removed her eggs and placed them in an incubator, hoping for the best.

Throughout the summer, while terrapin eggs in nests at Lt. Island were soaking up the sun, and long after those hatchlings had made their way into the world, these eggs remained in the incubator. In Wellfleet, diamondback terrapins usually hatch in 60 and 90 days. At 100 days, Tufts’ vets thought the eggs wouldn’t hatch but agreed to leave them in the incubators a little longer. At 112 days, two of the eggs hatched. And then a few days later, the remaining three emerged. By this time it was too late to put them into the marsh, too late for them to get their bearings and find a place to dig in for the winter. Instead, they would spend the winter and early spring swimming in a tank and eating.

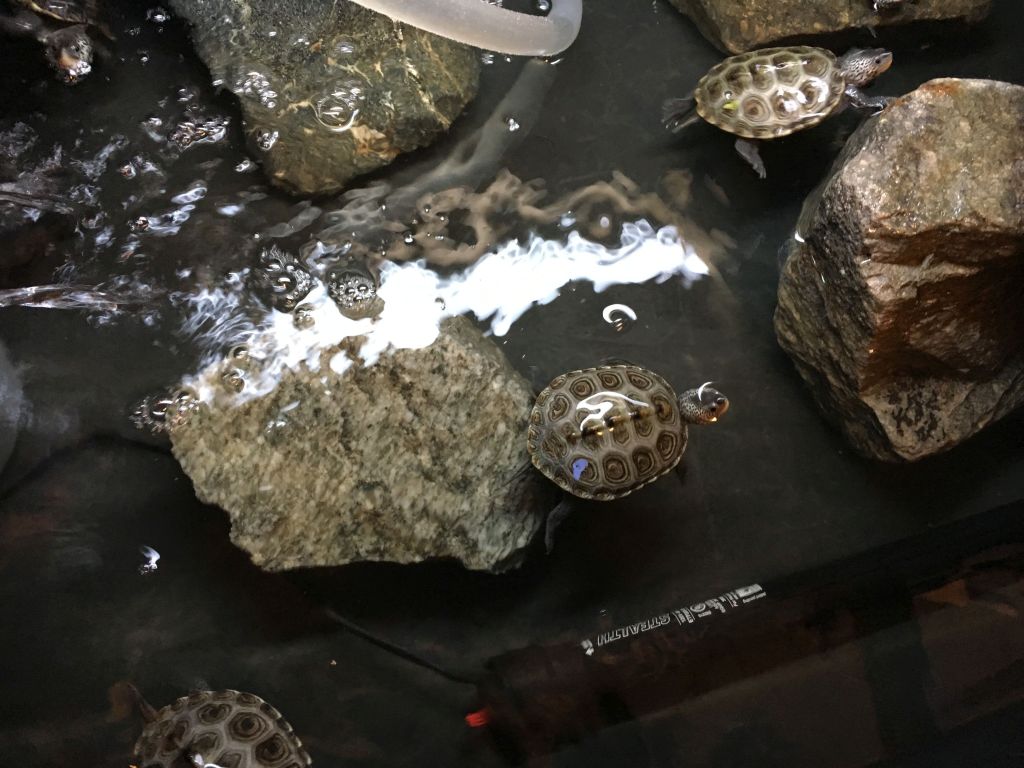

Overwintering at Tufts (Photo by Tim O’Brien)

And when you eat, you grow. By the time the weather had warmed enough to release these hatchlings in to the wild, they had grown to the size of three-year-old terrapins. Hatchlings normally don’t eat when they overwinter so they don’t grow bigger, ending the winter still the size of a quarter. Their shells had gone from soft and pliable to hard, protective cases and were no longer the tasty little morsels that are easy prey for everybody!

This head-started turtle is ready to go! (Photo by Karen Strauss)

We released these hatchlings in the way we always do, by lifting up some wrack along the edge of the marsh and placing a turtle under it. Then, we move a few feet over and repeat until all the turtles have been nestled under the wrack.

Sanctuary director Bob Prescott finds spots for each terrapin youngster on the edge of the marsh. It’s believed juvenile terrapins don’t become fully aquatic until after the first few years of their lives. (Photo by Karen Strauss)

These hatchlings hadn’t seen wrack or felt the marsh mud under their feet and I was interested to see what they would do. Two of them did nothing. They stayed where they were placed.

Where the heck am I? (Photo by Karen Strauss)

The others, after a few seconds, pushed their way out the wrack, determined to explore their new environment. One turtle, front limbs resting on wrack, looked around the marsh taking it all in.

Exploring! (photo by Karen Strauss)

And then we left them to figure out life for themselves. When I returned two days later, they had moved on.

It is always hard to release hatchlings into the wild, knowing that only a very few survive to adulthood. It was harder this time. These hatchlings had overcome so many obstacles to be born and now they were on their own. As is proper. But I wonder how they will adjust to finding their own food when they are used to being fed. How their one-year-old brains relate to their larger than average bodies. What they will make of a world with predators and people. In three or four years I will look for them.

Some of them have very distinctive anomalies on their shells, so I think I will know them again. This summer I will look for their mother, hoping to see her nesting. Finding her again would truly bring this story full circle for me.

Karen Strauss , a long time Wellfleet Bay terrapin volunteer, wishes to thank her fellow volunteer Tim O’Brien and the team at Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine for caring for these hatchlings and monitoring their successful development. Karen is also a horseshoe crab monitor and works with cold-stunned sea turtles. She is the newest member of the Eastham Conservation Commission.

This story is so inspiring, thank you for your hard work and care for these turtles. I will share it with my class this year.

Nice job on the blog post!

I loved this story. It brings me hope for wildlife. That people care and rescues can be successful.

I also like to think that I too would live the life of a wildlife helper, someone that is trained to monitor wildlife populations and contribute to citizen science projects.

Great job Karen! Thank you for getting these turtles back into the marsh where they belong.