July 5/6, 2017

Lime Kiln Farm Wildlife Sanctuary, Sheffield

Sketchbook Study of a Black-and-white Warbler, pencil & watercolor, 4″ x 6″

I plan an overnight excursion to visit two unstaffed sanctuaries in the Southwest corner of the state, and book two nights in a hotel in Great Barrington. By 8 am, I’m on the Mass Pike heading west. Driving through Palmer, I’m astonished by the extent of gypsy moth defoliation. For as far as the eye can see in every direction, the hills are brown and bare. It’s been reported that 900,000 acres in Massachusetts have been defoliated this summer, and one of the worst hit areas is the one I’m currently driving through…

I arrive at Lime Kiln Farm Wildlife Sanctuary by noon. It’s a warm, sunny day and butterflies are active around the gravel parking area. A red admiral, an orange sulfur and a tiger swallowtail flit around the lot, where my car is the only one present. It’s a pleasant spot, surrounded by meadows that keep the view open to the mountains on the horizon.

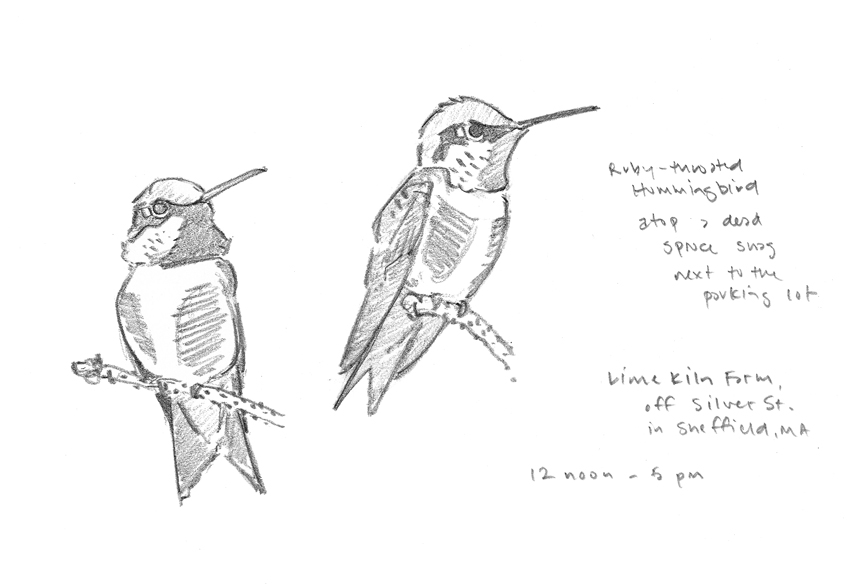

Sketchbook Studies of a Ruby-throated Hummingbird, pencil, 6″ x 9″

A copse of trees at the edge of the meadow includes some dead spruces, whose lichen-encrusted tops are a favored perch of a ruby-throated hummingbird. I set up my telescope and break for lunch, but am interrupted by frantic bouts of drawing when the hummingbird appears. In my final watercolor, I use a pose from my sketchbook that helps to coveys the feisty character of these birds.

detail of finished watercolor

I make one change to my sketchbook pose: I move the wingtips to BELOW the tail. It’s something hummers often do when perched, and to me it makes the bird more assertive. Ruby-throats just don’t seem to comprehend that they are VERY SMALL!

Hummingbird on Spruce Top, watercolor on Arches hot-press, 13.5″ x 10.25″

As I’m drawing, I can hear the calls of an alder flycatcher coming from a shrub swamp below the meadow, so I follow the Lime Kiln Loop Trail hoping to get closer to the bird.

The old Lime Kiln is an impressive structure, towering forty feet into the forest canopy. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the lime industry was a prominent part of the New England economy. Lime was a key ingredient in plaster and mortar.

When limestone is burned, it produces lime (calcium oxide). Lime kilns in New England used wood or coal to burn the limestone. The kiln was loaded with a cord of wood at the bottom, and then piled with limestone broken into basketball sized chunks. After the burn, the lime was loaded into casks for transport. By 1900 the lime kilns in New England were shutting down due to competition from newer building materials and cheaper lime from other sources.

I crawl about the relic kiln, shooting it from various angles, and imagine the roar of a cord of wood blazing in the belly of the old kiln. FEEL THE BURN!

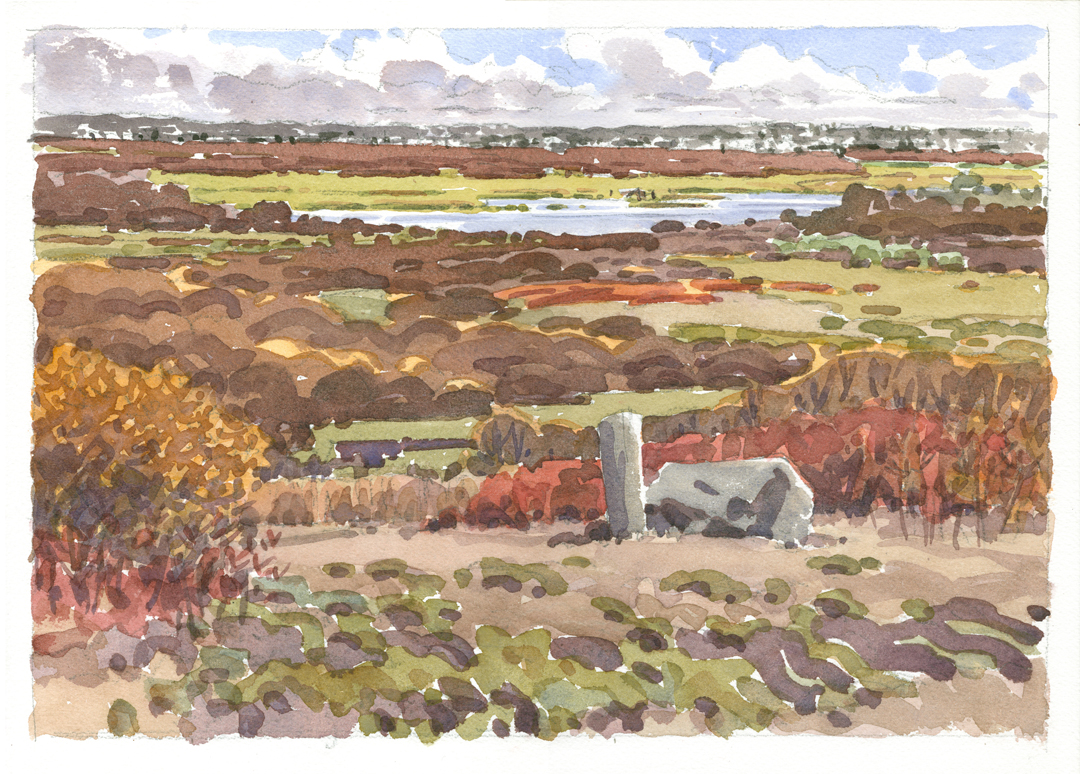

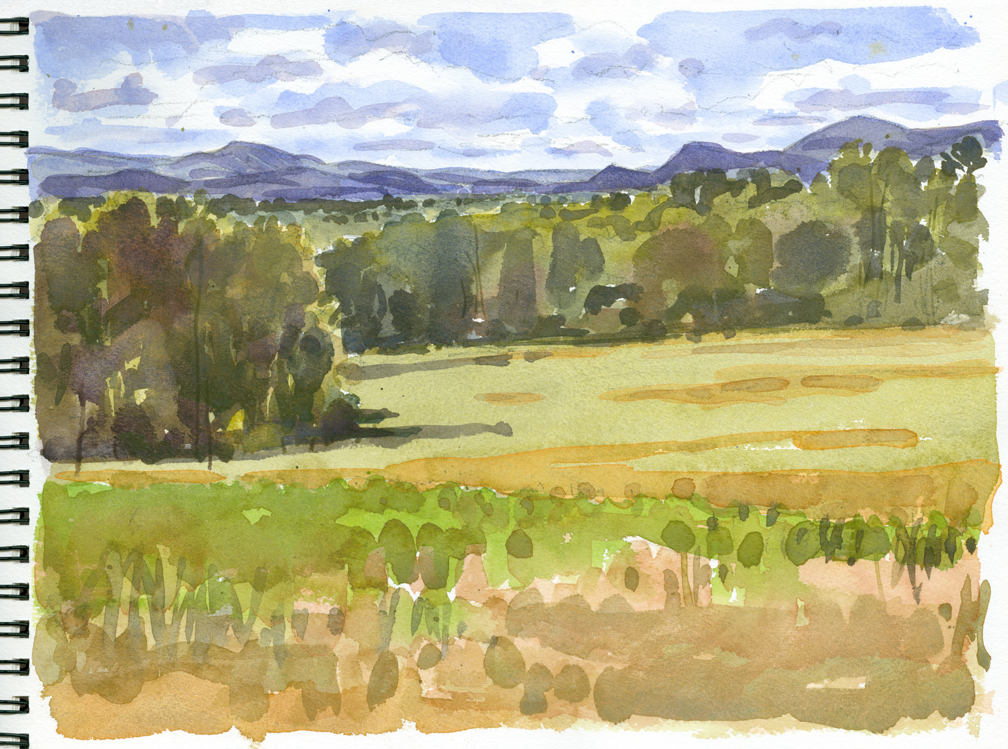

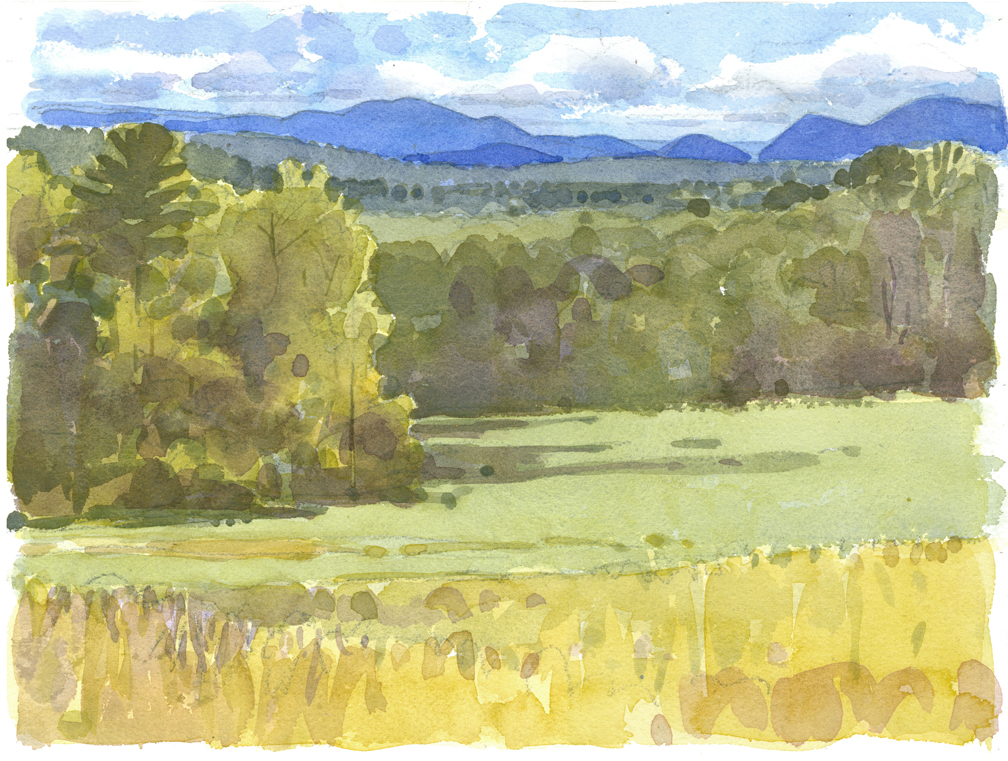

I follow the Quarry Trail, then the Taconic Vista Trail to the “Scenic Vista”. And, it is indeed SCENIC – with the Taconic Mountains to the west and the nearer Berkshire Hills to the north, all viewed across a wide meadow. A yellow-throated vireo sings it’s “three-eights” from a big oak while I set up to paint.

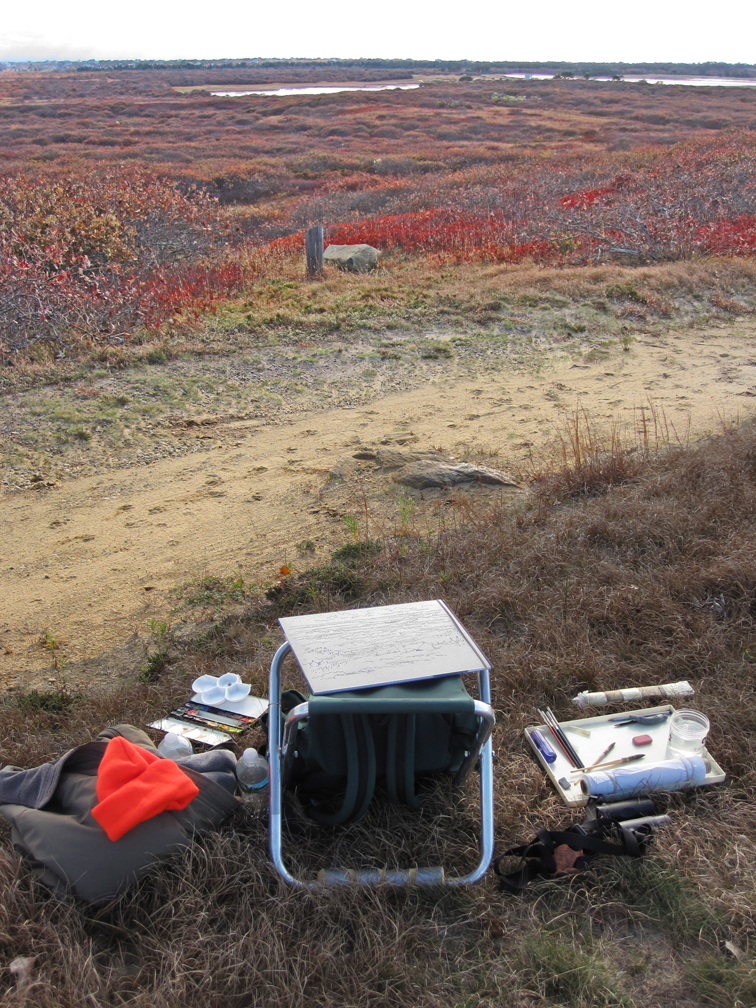

painting in progress at the Scenic Vista

I’ve written previously about the artistic challenges posed by the unbroken greens of summer in New England, and here again I’m faced with the challenge: how to deal with all that GREEN!

View of the Taconics I, watercolor on Arches cold-press, 10″ x 13.25″

My first attempt at painting the scene disappoints me – it feels heavy-handed and overworked, so I immediately start another version.

View of the Taconics II, watercolor on Arches cold-press, 9″ x 12.25″

On my second attempt, I scale back to a smaller sheet and deliberately compress the landscape from left to right. I make the mountains more prominent and paint them with a purer, brighter blue. I pay special attention to the zone that links the distant mountains with the nearer trees (i.e. where the greens shift from cool to warm). I simplify the foreground and bring more light into the closest trees on the left.

I’ll leave it to YOU to decide which painting YOU prefer!